Diary: (1) Andrew Hui on the Birth of the Private Library

We gather in libraries, or take a voyage around our room, another way of gathering

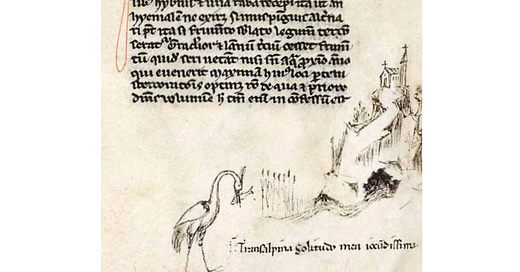

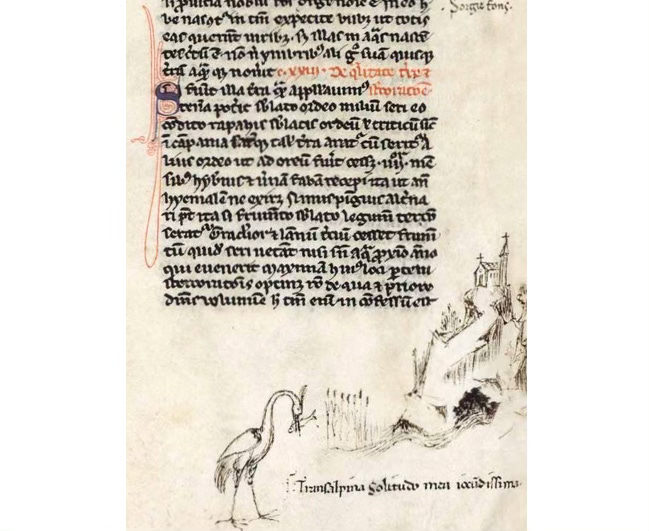

Petrarch drew his little house on a hilltop with a heron in the margin of his copy of Pliny’s Natural History with the inscription, “transalpina solitude mea iocundissima” (“my most pleasing transalpine solitude”). He wrote “isolation without literature is exile, prison, and torture; supply literature, and it becomes your country, freedom, and delight.” Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, MS Lat. 6802, fol. 143v

If you are reading this, gentle reader, you have probably been to a library. You may have one of your own. You make lists of books that you have read, want to read or want to write yourself. You buy, borrow, and give away books. Perhaps you organize your library by author, period, region, gender, size, color of the spine, order of acquisition (like in medieval monasteries), or, very likely, haphazardly. Maybe you arrange your books like the art historian Aby Warburg, who classified his collection according to the “law of the good neighbor,” that is, how good a conversation a book might have with the one next to it. His namesake library in London today still follows this quirky principle of serendipity. Georges Perec, in his playful “Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books,” says, “like the librarians of Babel in Borges’s story, who are looking for the book that will provide them with the key to all others, we oscillate between the illusion of perfection and the vertigo of the unattainable.” You might even, like me, practice the refined art of what the Japanese call tsundoku—buying books and not reading them.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.