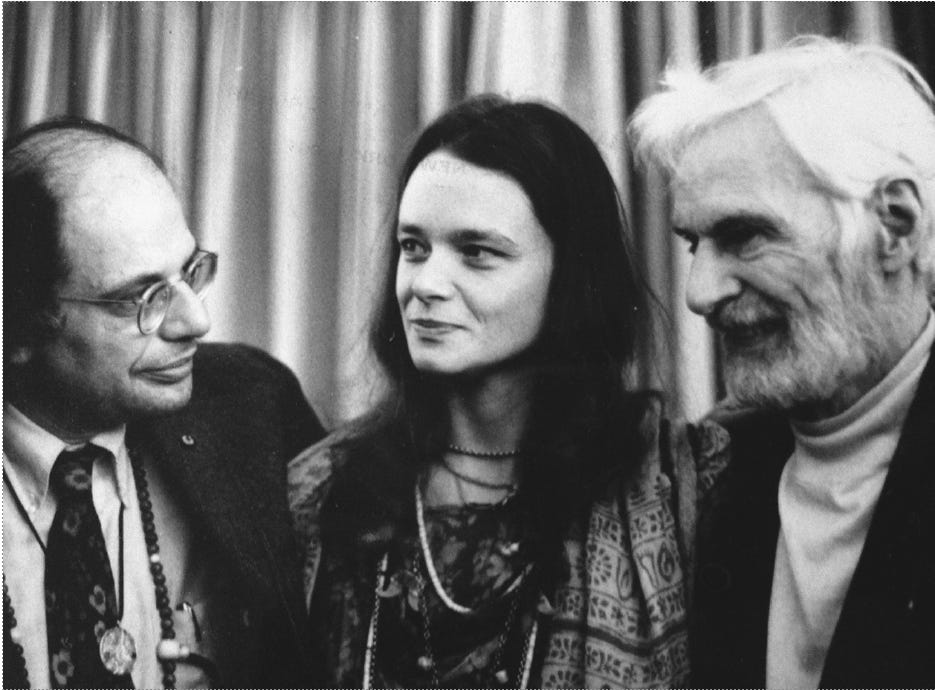

Anne Waldman with poet Allen Ginsberg and poet/dance critic Edwin Denby at the Gotham Book Mart, 1970. Photographer unknown, Anne Waldman Archives. Anne Waldman and Allen Ginsberg would go on to found, with Diane DiPrima, the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University, in Boulder, Colorado.

I sat on Lead Belly’s lap as a baby. Patti Smith, my neighbor, insisted I start with this tantalizing detail. Wear it as an amulet.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.