For those of us teaching English in a small liberal arts college, two subjects prompt anxiety: Identity and the Internet. Identity preoccupies most everyone, especially those who enthusiastically embrace both Identity and its smarter younger sibling, Intersectional Identity. The comic-book version of what’s going on in the academy might lead you to believe that there are exactly two sides in the fight: the decriers of “identity politics” and those who live for it. But it is not so. Depending on the particular campus, there might be many groups to which students or faculty might say they belong and whose identity tags they embrace, but there are even more groups to which one might be accused of belonging, often on inscrutable grounds. For instance: “Antifa” might be a political identity one claims for oneself; or “antifa” might be a stinging slur from a political opponent against someone who does not want to be thought quite so radical; alternately, it might be a slur on style grounds, since after all “antifa” is so 2017. For another instance: Recently I, a white poet, was advised by a nervous white colleague that perhaps I should stop teaching the poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks and other black poets in my courses, lest I be accused of appropriation.

An old campus ideal, embodied in that harmonious phrase “diversity and inclusion,” seems to have been jettisoned for all practical purposes, as it gets harder to imagine anyone wanting to be included with anyone else.

No less direly, the Internet—by which I inaccurately refer to the material found on all screens—induces geschrei. We who teach literature and writing have noted that the last decade has seen a contraction of engagement in actual reading by our students; and, with it, of their attention-spans; and with that, a conviction that any of it matters. If this is not due to the transfer of reading life from the page to the screen, I don’t know what else might account for it. If one more student says to me that, as an English major, she wants to concentrate not on literary studies but on creative writing “because I don’t like to read”—and yes, I have actually heard this, many times—I don’t know what I will do. Who, if I cried out, would hear me among the throngs of angels?

Thus tormented by my workaday sphere, I find myself longing for coziness—or even just simple friendliness. That the Danish word for this, “hygge,” has prompted articles in magazines, entire books, chat show panels, and social media posts for the last two years suggests that plenty of other people are looking for it as well. Think of a fireplace, a hot mug of tea, comfy old clothes, conversation, and no need to hurry: that’s hygge. It is the opposite of having someone call you “an enabler of rape culture” because you assigned Ovid’s Metamorphoses; it is the opposite of scrolling through Twitter to find someone to attack, or scrolling through Instagram to find someone to envy.

I have now read several books about hygge, and can assure you that you do not have to. Some are more annoying than others, but with minor variations all define hygge as a warm hearth, good company, and simplicity. (Had Thoreau had been fonder of other people, his would have been a model of the hygge life.) Sometimes “mindfulness” language creeps in, but I am pretty sure most Danes would sock you if you tried to suggest that something so new-agey has anything to do with their hygge. If you don’t have a fireplace, light some candles. Sit and chat; maybe play music together. A game of charades or hunt-the-slipper would be quite hyggelich, as would reading aloud, eating heavy food, and snuggling the children close. The ideal of hygge, it seems, is a mythical version of nineteenth-century Scandinavian family life.

Well before the hygge craze, I had realized that my own version of home comfort was taking on a decidedly old-fashioned cast. Over the years my taste has grown increasingly rustic—as an entire Victorian dinner service, sets of lace-edged napkins and champagne flutes have gone to Goodwill, to be replaced by mismatched earthenware and stoneware plates and thick old glasses. Not a single piece of wood furniture with a surface requiring polish remains in my house.

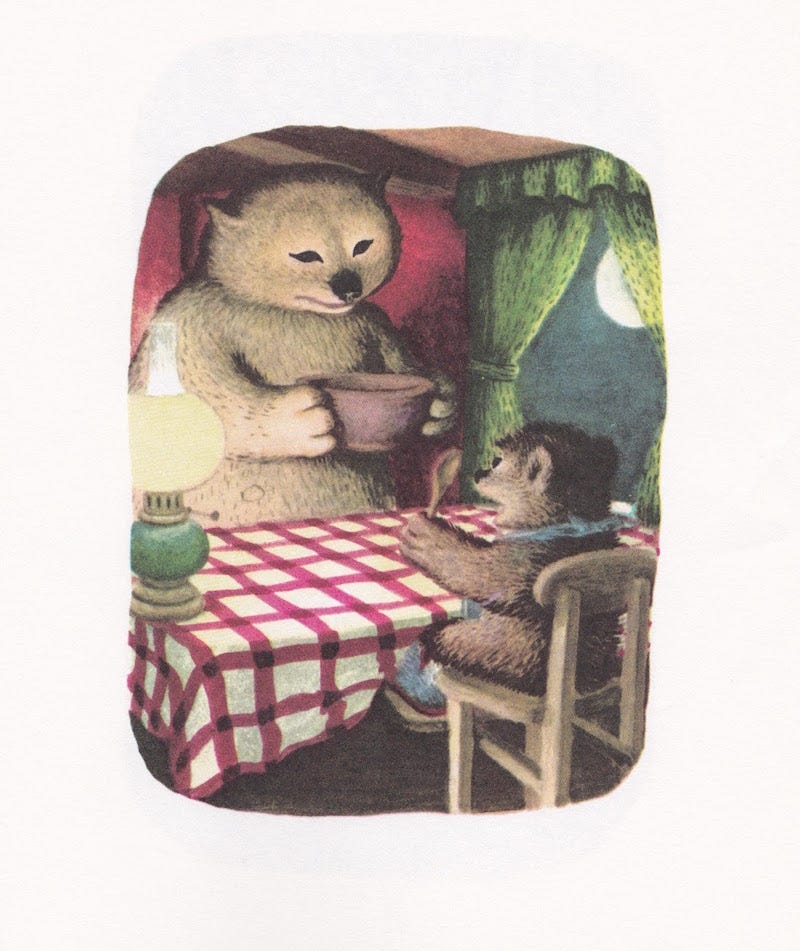

The other day, I was gazing fondly at my low, rough-edged dining table and rush-seat chairs, and with a gentle shock realized that my house has come to resemble something from a drawing. From many drawings, in fact: those wonderful, soft, charcoal book illustrations by Garth Williams. To my combined delight and chagrin, I discovered that I have made my very small house into one that could, plausibly, be lived in by the Little Fur Family—or by the Ingallses, my own Little House in the Big Woods.

That I do not live in the big woods, and certainly do not live in a tree (as the Fur Family does), may make my choices seem quaint. But this slow and steady reversion to my childhood dream of coziness, found once upon a time only, and miraculously, in those drawings, strikes me as one of the most distinctive ways that I have learned how to live and thrive. Even as the strife of the greater world presses on us—from our president and his circle to the surge of unkindness, suspicion, and name-calling that marks this moment in the academy—nothing, it seems, could be more important than lighting a candle, a hygge candle if you will, rather than cursing the darkness. Every time I make tea for a friend, lighting the tea-light under the pot, I am remembering, in my own actions, those of the ancestors. Through all our generations, and all the way back to the hearths of eastern Africa. May they live on through me and those I love.

April Bernard’s most recent books are Miss Fuller (a novel) and Brawl & Jag (a book of poems).

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in box. Thank you for your subscription! As a subscriber you can read our full archive at bookpostusa.com. Please help us spread the word about Book Post: your subscriptions keep us going, supporting writers and books and reading across America.

Coming soon: Elaine Blair on Sally Rooney, Àlvaro Enrigue on Gabriel Garcia Marquez, more!

Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn is Book Post’s winter partner bookstore. We support independent bookselling by linking to independent booksellers and bringing you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. Spend more than $100 at Greenlight and we’ll give you or a friend a free one-month subscription (send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com).

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

Image: From The Little Fur Family, by Margaret Wise Brown, illustrated by Garth Williams

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

“Hygge. It is the opposite of having someone call you “an enabler of rape culture” because you assigned Ovid’s Metamorphoses”