Diary: Carolyn Ferrell, “We must trust in what is difficult” (Part 2)

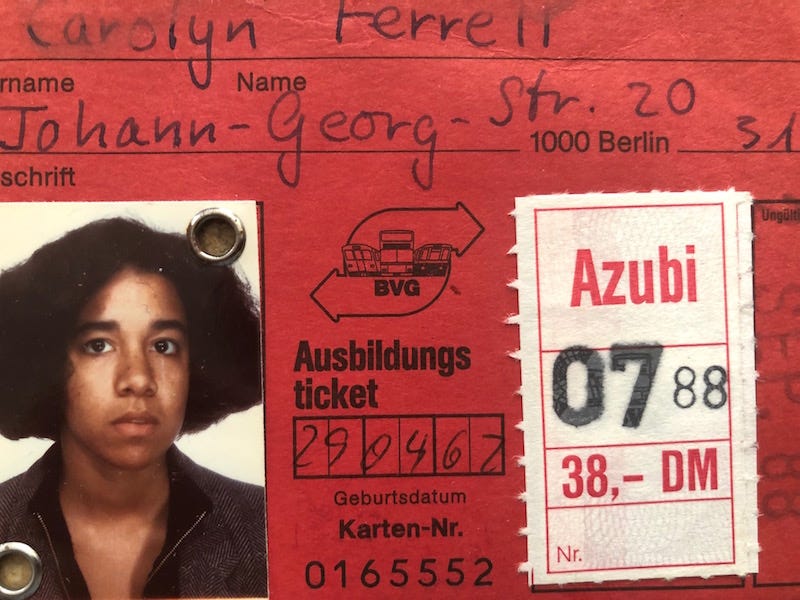

Carolyn Ferrell’s student bus pass, Berlin, 1988

In West Berlin, I found myself crying often. It was the winter of 1985, and, though I’d tenaciously planted myself there two months earlier, I had no friends. I lived in an unheated apartment, and my meager student loan left me broke by the middle of each month. The boy I’d followed there told me I should commit myself to a mental asylum. I hated West Berlin and its grimy, xenophobic residents. I had been forced to move a few times, and when I went looking for a room to rent, people often slammed the door in my face saying, “KEINE AUSLÄNDER!” My relatives belittled my concerns about the racism I encountered. Why did I want to study in Germany if it was so bad, they asked? Had my American education been so lacking? Once, while visiting my uncle in his small village outside Kiel, I took a walk in the forest and was accosted by an elfin elderly man. “I know where you’re from!” he shouted, “Africa!” Another time, a relative I hadn’t seen in years greeted me at her door with an apron and a bucket of soapy water. “Hilfst Du mir beim Fensterputzen?” she asked. I wasn’t there to clean her windows, I explained.

Sitting in my gray Neukölln apartment one frigid day, bawling into the overseas line, I tried to coax my mother to drop everything and come to me. I wanted her to realize she missed Germany—even if gritty West Berlin was not like the northern Germany of her youth. On some level I was living the life she should have had—a university experience, the chance to travel Europe. Payback for all those hard years on Long Island. “Don’t you want to come back home one day?” I asked, sniffling into the receiver. But I knew the answer without her having to say a word. She’d been in the U.S. for more than forty years. For all the hardships, my mother loved the life America had given her. She loved her independence. She loved being around different kinds of people and not breathing in a Nazi past.

I was miserable in Berlin, but it was there I began to learn that the horrible, wonderful treasures of my childhood were actually jewels. I would always eat that spoiled milk. I would wish for that James Brown record to be playing in our house. My church was not a brick building where Easter coats and satin sashes announced the pinnacle of girldom—solid black girldom, without any trace of whiteness. That was not me. My church was my hand around a pencil, my fingers on the computer’s keyboard. “Do you suppose that someone who really has [God] could lose him like a little stone?” Rilke asked before answering his own question. “We must trust in what is difficult.”

Eventually, I came back to New York and worked on my short stories, many of which took me back to that block of Cape Cods and that bowl of sour milk. “You mustn’t be frightened, dear Mr. Kappus,” Rilke wrote in 1904, “if a sadness rises in front of you, larger than any you have ever seen … you must realize that something is happening to you, that life has not forgotten you, that it holds you in its hand and will not let you fall.” This was the best writerly advice I could have gotten as I sat in West Berlin, devising ways for my mother to join me but knowing I was now on my own.

[Read Part 1 of this post here]

Carolyn Ferrell is the author of the book of short stories, Don’t Erase Me. This essay is drawn from her longer memoir, “No Indifferent Place,” which will appear in the anthology, Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents, this September.

Book Post is a by-subscription book-review service, bringing short book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to subscribers’ in-boxes, and other tasty items celebrating book life, like this one, to those who have signed up for our free posts and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend! Recent reviews include Sarah Kerr on Carlos Bulosan and Adam Hochschild on unsung heroes of the Nazi resistance. Coming up we have Mona Simpson on Lewis Hyde and Emily Bernard on Imani Perry’s Lorraine Hansberry.

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s current partner bookstore is The Raven in Lawrence, Kansas. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram