Diary: Geoffrey O’Brien, Paris—Dream of book lovers

Often I daydream of a city awash in bookstores—not just in one or two neighborhoods, but emerging on the most unexpected streets and alleyways—bookstores with histories, some around for many decades, some dating back more than a century; in a few copiously stocked establishments, a huge range of books—popular, literary, scholarly, obscure—promiscuously sharing the same shelves; in other, smaller spaces, books meeting a multitude of specialized tastes and interests, acquainting you with the products of ever more esoteric publishers and the writings of authors perhaps unknown to you who here receive the veneration due to classics. With each step—each fresh book cover—you find yourself initiated not only into new releases but whole new fields of knowledge—or old fields of knowledge, in dimmer interiors where antique volumes fill every available bit of room, sometimes simply piled up on the floor as in someone’s overcrowded apartment. When the daydream becomes too persistent, I figure it is time for Paris again.

Paris is many cities but for a reader it is most indelibly this city of bookstores. A full charting of them would uncover multiple enfolded realms of intellectual history. Since the time I had the good fortune to study there briefly as a teenager, Paris has been the place I had to keep going back to, simply to find out what is new, what has been coming out since the last visit, what fresh approaches have been tried, what unsuspected information has appeared on the table—and to find out as well what new retrievals have been made from a past apparently limitless in its capacity for redefinition. It seems almost inevitable that there will be another Alexandre Dumas novel rescued from oblivion, another addition to the canon of Marcel Schwob, another neglected libertine author of the sixteenth century, another crucial yet curiously unknown document of early modernism, another previously untranslated manuscript of Fernando Pessoa.

Always there is a sense of surprise, accompanied by the frustration of not having enough time—or, early and late, enough French, and enough different kinds of French—to take full advantage of the feast on display. There could be no greater inducement to sharpen one’s skills. The profusion has seemed to embody what culture is supposed to mean, not just French culture but world culture, since one of the signal aspects of French publishing has been its restless curiosity about what is being written in other languages. In a fashion that puts the Anglophone world to shame, Parisian bookshops make available the works of Asian and European and African writers—as well as American writers unjustly ignored in their homeland. I remember years ago longingly contemplating French versions of romans noirs by hard-boiled Americans David Goodis and Jim Thompson that were at the time out of print in English.

Just scanning the titles of books spread out on the tables and shelves of, for example, La Hune—the bookstore that was patronized early on by Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, and many others, and that for some fifty years exercised a radiant influence amid Café de Flore, Aux Deux Magots, and other legendary haunts of bohemian Saint-Germain-des-Près—provided an instant update on the emerging ideas and fascinations of the moment, whether in art or politics, ethnology or philosophy, cinema or poetry. La Hune means “the crow’s-nest,” and the perilously winding staircase connecting its two levels was itself an indication that to roam through the store was to participate in a voyage of reconnaissance. It was always my first stop in Paris. When it closed in 2012, replaced by a Louis Vuitton outlet, it seemed as if the end was at hand for a unique culture no longer resistant to the machinery of capital that had ravaged its counterparts elsewhere in the world. In fact it reopened around the corner a few years later, only to mutate into a more narrowly defined establishment specializing in photography books. The new venue, heavily damaged in a fire last year, seems now to have remade itself as a gallery. In the meantime the neighborhood’s bookselling credentials are sustained by the spacious L’Écume des Pages (174 Boulevard Saint-Germain), whose stock ranges comprehensively across genres and disciplines, with a good selection of art, photography, and travel books, an ideal place to browse were it not that its top shelves soar beyond reach and almost beyond sight.

Parisians lament that the city’s bookselling culture is not what it was, despite government policies that have helped shore it up, notably by restricting discounting. The inroads of Amazon and other on-line sellers cannot be kept altogether at bay—one need only watch Olivier Assayas’s new film Non-Fiction (which opens in the U.S. in 2019), set in the publishing world, to gauge how the same inexorable forces, from digitization to declining readership, now afflict Europe as well as America. There is no question that the number of distinctive specialized bookshops in Paris has dwindled. Yet for a New Yorker who in recent decades has witnessed the swift decimation of the city’s once glorious array of independent bookstores to a hardy few, Paris continues to dazzle with the range of its offerings. Not only are there many places to find books; you find different books in each of them.

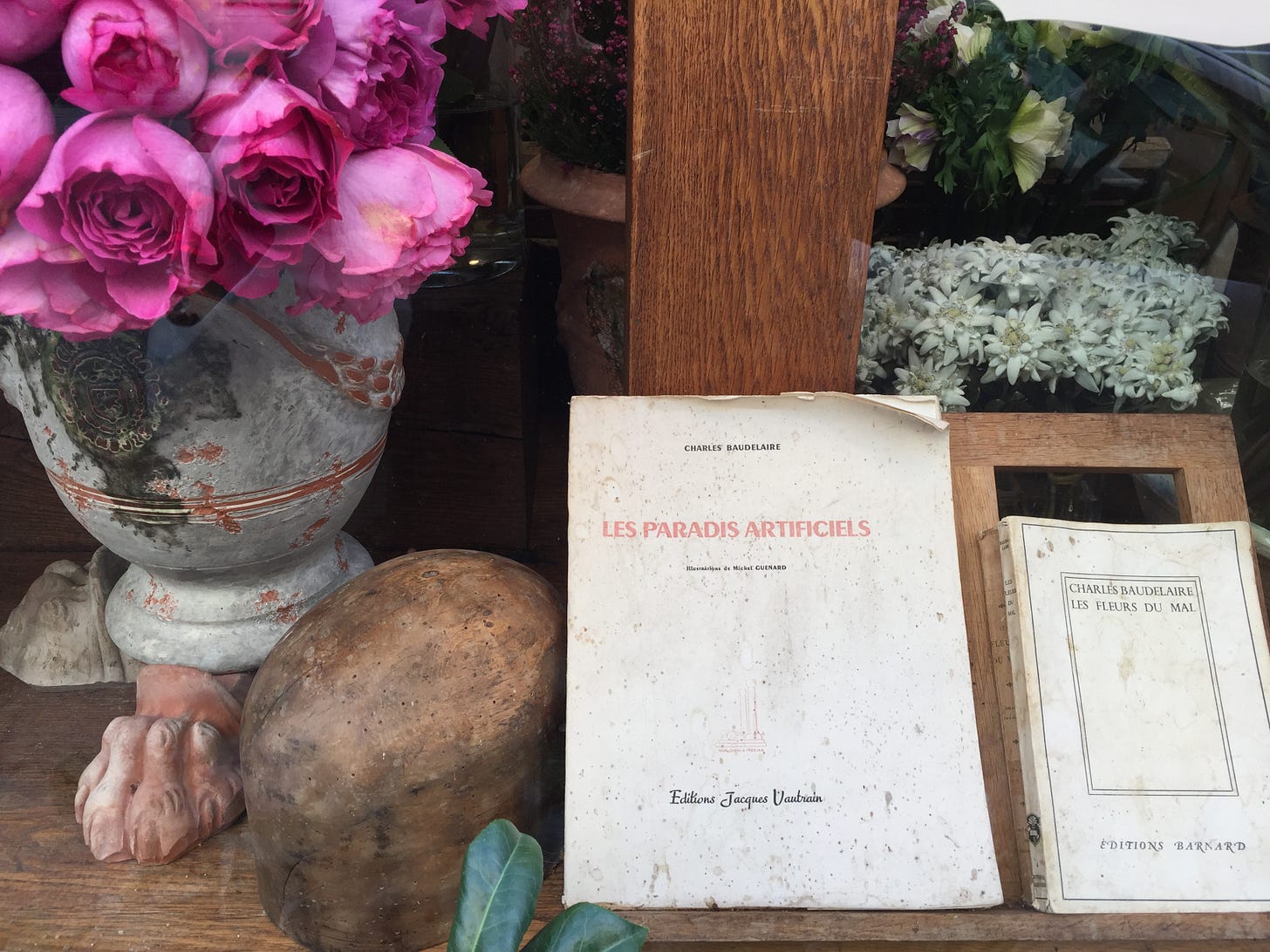

Books seem to be everywhere, not only in bookstores, as if to underscore that Paris is in some sense the city of the book. A florist places two books in the center of a window display: Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal and Les Paradis artificiels. The bouquinistes whose bookstalls line the Seine are a familiar postcard image, but it is still possible to come upon the out-of-print oddity you were looking for, whether a 1930s fashion magazine or a lurid true-crime periodical of the Belle Époque. In crowded little antique shops along Rue Notre Dame des Champs you can find, alongside ottomans and Art Deco lamps, choice clusters of gently used volumes of Gallimard’s comprehensive series, the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, whether your taste runs to the maxims of La Rochefoucauld or the nouveau roman experiments of Nathalie Sarraute. In one of these I was delighted to find the Pléiade’s illustrated Album Balzac, before being informed that the asking price was 86 euros: “Everyone is always looking for the Album Balzac. It was the first in the series.”

Large department stores like Galeries Lafayette and Bon Marché house book sections that anywhere else could be free-standing destinations—not to mention the third-floor book section of the cavernous FNAC (136 Rue de Rennes), which makes up for its lack of intimacy with the sheer quantity of its holdings. In the Marais, La Belle Hortense (31 Rue Vieille du Temple) is a “bar littéraire” where you can browse an elegantly tended selection of literary volumes while sampling the wine list. The lobby of the live theater-and-cinema complex Lucernaire features a stock of theater books; the gift shop of the Musée de l’Orangerie offers an abundance of recent books on art, photography, and film.

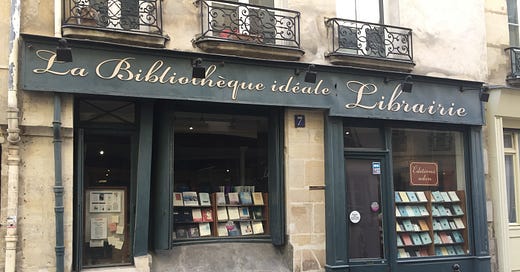

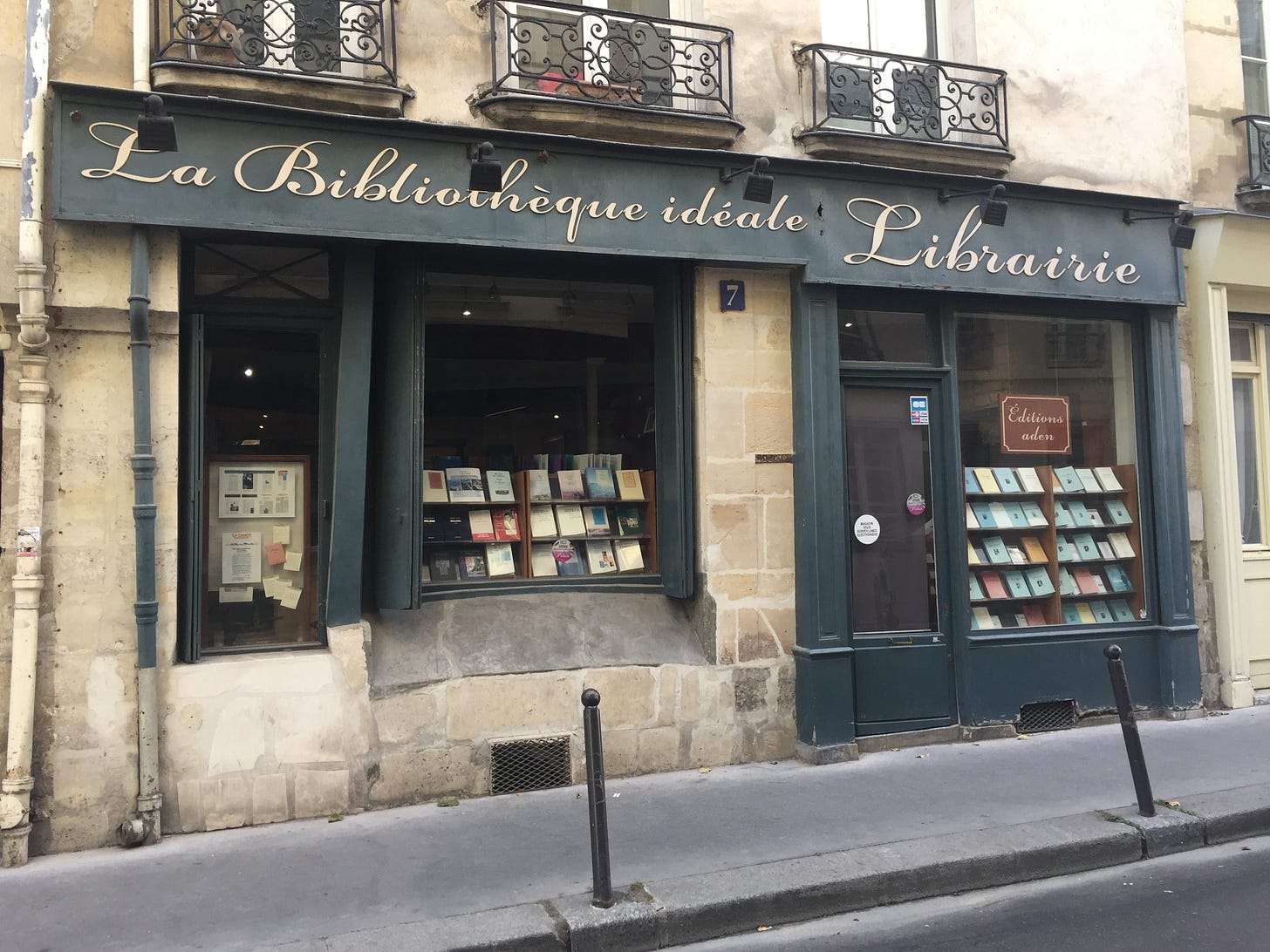

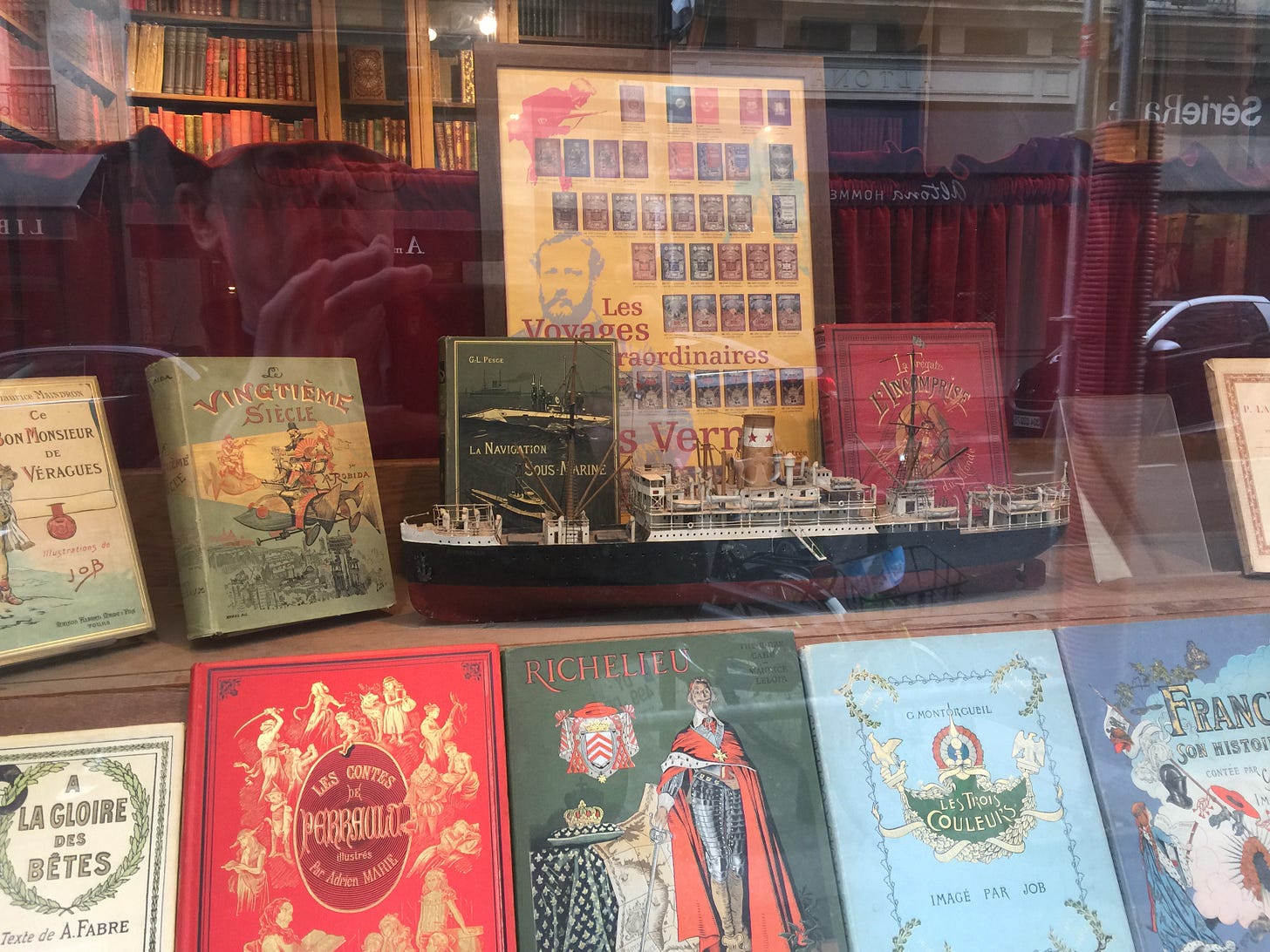

Then there are the bookstores proper, whose names alone are often sufficient inducement: Le Dilettante, La Bibliothèque Idéale, Librairie de l’Inconnu. The latter proved to be a disappointing mélange of lunar calendars, guides to the Tarot, and the like, with the most prominent window space reserved for the companion volumes What Your Dog Knows and What Your Cat Knows. But you never know what you will find in these windows. Vitrines around the Sorbonne and other academic precincts display freshly-minted scholarly works on everything from the poetics of octosyllabic couplets in medieval literature to a new biography of the hermetic and endlessly fascinating poet and sinologist Victor Segalen. Another window displays a rich assortment of introductory texts for studying the languages of Indonesia, Burma, Laos. The Librairie Monte Cristo (22 Rue de l’Odéon) offers a sampling of the octavo first editions of Jules Verne’s novels, along with other similarly irresistible antiques: fables, adventure stories, speculative fictions such as Robida’s The Twentieth Century (1882), an illustrated panorama of the “electric life” of 1955.

So often there is an experience of stepping into one of these bookstores and stepping right out of time. Here are five—an impossibly small selection—where a variety of worlds are laid open to inspection.

Librairie du Cinéma du Panthéon (15 Rue Victor Cousin), perched in back of the Sorbonne, is currently the most accessible film bookstore in Paris. That there are not more may testify to a waning of the cinephilic passion that once held sway here. Le Minotaure, with its appropriately labyrinthine association, where I used to immerse myself in the latest issues of Cahiers du Cinéma and Positif and Présence du Cinéma, is long gone, and the marvelous Scaramouche, a veritable den of closely-packed cinematic arcana, closed last year. The Pantheon shop is less epic in scope but still teems with a multilingual assortment of directorial monographs, essays in theory, visual compilations, and periodicals current and otherwise.

Le Coupe Papier (19 Rue de l’Odéon), which has been around since the beginning of the 1960s, must have few peers worldwide in its devotion to all aspects of theater. Books new and old on stage history, dance, puppetry, the circus, and every aspect of theatrical technique and theory, along with a rich archive of theatrical periodicals, fill every available space, with pride of place given to as thorough a stock of play texts ancient and modern as can be imagined. This is bookstore as cultural institution, with a sense of mission manifest at every turn.

L’Harmattan (16 Rue des Écoles) is the flagship store of a publishing enterprise and cultural center founded in the mid-1970s, focused primarily on sub-Saharan Africa but encompassing a much wider geographic range, as its sign indicates: AFRICA – INDIAN OCEAN – ANTILLES – ARAB WORLD – SPAIN – PORTUGAL – LATIN AMERICA – ASIA. The multileveled bookstore is the equivalent of a very serious research library, divided primarily by region. Here can be found in translation the literature of scores of different languages. Colonial and post-colonial history and politics can be studied in microscopic detail. At random you might come upon a survey of contemporary theater in Mali, Georges Clemenceau’s account of his voyage to Argentina, or Zeami Motokiyo’s fifteenth-century treatise on the art of the Nō theater. In short, a school in the form of a bookstore.

To enter L’Amour du Noir (11 Rue du Cardinal Lemoine) is to step into an attic where an especially orderly hoarder has amassed a century’s worth of crime fiction. Collectible editions of pioneering French writers like Emile Gaboriau and Maurice Leblanc and their successors such as Léo Malet and Jean-Patrick Manchette are jostled by volumes from Gallimard’s legendary Serie Noire, with its repertoire of once-underestimated Americans including David Goodis, Ed McBain, James M. Cain, Horace McCoy, and so many others. Georges Simenon occupies a wide swath, his staggeringly copious output neatly arranged by publisher, so that you can trace successive decades of publishing history and savor the fragile charm of the cheaply printed paperbacks of the forties and fifties. From that decaying paper the aroma of a whole subterranean culture emanates. As a bonus, a central table is piled high with back issues of Cahiers du Cinéma and other vintage film magazines.

Finally—now that La Hune is gone—there is the store that offers the best snapshot of French literary culture in its current state: Compagnie (58 Rue des Ecoles), situated directly opposite the Sorbonne, is not the largest Parisian bookstore but through deft selection it offers a staggering range. Happy hours can be spent examining every item on their shelves and tables, marveling at the organization that makes the store itself seem like a compressed encyclopedia: something that every bookstore should at least aspire to. My favorite table is right by the exit, and features recent books of poetry. This time around I was delighted to find slim volumes of classic works by the great Charles Reznikoff (1894–1976)—among them Jerusalem the Golden and In Memoriam: 1933—newly translated in editions so elegant I wanted to read them all over again, in French this time.

Geoffrey O’Brien’s books include The Phantom Empire: Movies in the Mind of the 20th Century, Stolen Glimpses, Captive Shadows: Writing on Film, 2002–2012, and, most recently, a book of poems, The Blue Hill. Photographs are the author’s; we’ll be posting more on social media!

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing to your in-box book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers, plus a few other treats, such as this one, for followers of our free updates and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend!

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s December partner bookstore is Greenlight. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram.

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”