Unexpectedly, I, a historian of the Roman Empire who has spent most of her life as an American university professor in the Midwest, found myself this summer in the heart of Tel Aviv, every Saturday night from 7 to 10, joining thousands of Israelis hoisting Israel’s national flag and shouting DEMOKRATIA!

I surprise myself. I could never abide large crowds or loud noises. But there I was, participating in an ever-escalating war of words over the survival of democracy in Israel. According to labels disseminated by the government and its allies, I am a “traitor.” It is unclear whom and what I was betraying. No one bothers to explain. The government claims my fellow protesters and I are financed by foreign entities. No specifics there either. When I check my bank account I don’t see anything coming in.

I am torn. I was born in Israel. I have lived much of my life in the US. I have travelled to Israel every few years, mixing tourism with research. Why join a fight for democracy thousands of miles from home? Because it is a matter of checks and balances, a foundational tenet of liberal democracy. Because what happens in Israel can happen elsewhere, not least in the US. In early January, days after its inauguration, the newly constituted government of Benjamin Netanyahu announced a series of judicial reforms aimed at dismantling the existing fragile balance between the executive and the judiciary in Israel.

The prime target was the Israeli Supreme Court, the only body with authority to question and, if need be, obstruct the legislative branch. Israel does not have a constitution. All proposed legislation passes through the unicameral Knesset (parliament), where Netanyahu’s coalition commands the votes of 64 out of 120 members. In late July, the coalition voted to abolish the Unreasonableness Clause, the basis for judicial challenges of legislative action. The implications of this step are far reaching, allowing government to pass laws without judicial hindrance or opposition. At the moment of writing, a historical paradox is emerging—the Israeli Supreme Court (whose president is a woman) discussing the abolition of the very clause (reasonableness) that undergirds its authority. No less threatening is the specter of all-male rabbinic courts, who control laws that govern the domestic sphere of Israel’s Jews, directing Netanyahu’s ultra-orthodox partners to defund secular schools and reduce the participation of women in public life. They also open the door to increasing persecution of Arab and other non-Jewish Israelis.

I was in Israel from early May through the summer. By the time I arrived Parliament seemed more committed to battling protesters against these proposals than to governing. In spite of mounting heat and humidity I began joining the Shabbat protests. I found that I actually enjoyed the Sabbath certainty of knowing exactly what I was going to do and where I was going to be each week between 7 and 10 PM.

I found I liked the brief camaraderie prompted by the protests. I stood shoulder to shoulder with complete strangers. I smiled at those who passed by me and was ready with doggie bags to collect doggie poo. I was fascinated by the canine calm amidst so much clamor. I am used to worrying over my students, problems of research, academic policies. Was it a sense of helplessness that goaded me to join the dissenting masses? A belief that my presence might count? On the streets of Tel Aviv I was a protester among many, one of countless individuals striving to make a tiny difference, but a difference nonetheless. Many brought children. They were a lively reminder of what the protests were primarily about—maintaining a viable democratic future. It is a chapter, my chapter, in a larger story that is embracing us all.

I especially reveled in the nascent street literacy. Every Saturday I contemplated the numerous signs that graced the protest. I carefully sifted through what I dubbed the “avenue of aphorisms,” a series of placards pasted to the road in two parallel lines offering comment on the situation. Many are tinged with Israeli humor (“Let criminals appoint judges: What can possibly go wrong?”). I am far from alone. Reading has emerged as a dimension of protest. We walk slowly, stopping for a few seconds at each placard, often exchanging glances with whoever stands next to or across for us, smiling wryly. It is a companionship of reading.

Street literacy is creative. I am the proud possessor of a crisp, freshly minted note of 200 Israeli shekels (about $55 US). It is not the genuine item. Rather, it is an example of the verbal imagination that the demonstrations are awakening. It is strikingly similar to the real 200 shekel note. Both notes bear the stern portrait of Nathan Alterman, the great Israeli poet. The real one displays two lines from his Morning Song:

We love you, Homeland,

In joy, in song, and in labor.

The new 200 Israeli shekel note presents more words, in plain prose:

This money could have been yours, it could have expanded a hospital, it could have repaired a road, it could have added classrooms. But it was given to freeloaders. THIEVING GOVERNMENT.

I delight in perusing this note minutely. Historians of antiquity are trained to analyze the imagery and inscriptions of artefacts to reconstruct what brought them into being. Ours is a study in popular imagination, a guess at what ancient beholders of imperial portraits would have thought when fiddling a coin before paying for a slave or a donkey. This piece of ersatz currency references the staggering outlays the current Israeli government is dedicating to its coalition partners, the messianic and extreme right.

Every Saturday I looked forward to the short speeches that arise from the protests. Speakers varied greatly, from former PMs and government ministers through notable inventors, writers, and public intellectuals to activist high-schoolers. As soon as they mount the platform silence descends. In early April, on the eve of Passover, novelist David Grossman addressed protesters in Jerusalem with the Haggadah’s line: “How does This Night differ from all Other Nights?” His answer, like the shekel note repurposing deeply familiar themes, “Because of us, the protesters, because we have changed it!” In Tel Aviv, at the beginning of August, Yuval Noah Harari, known for looking backward at human change, intoned: “Stop the revolution or we will stop the state.” Writers, greeted with loud cheers and blows on plastic horns.

I engage in the semantics of t-shirts. By now I own three, with slogans relating to women, education, and democracy. Wearing the blue one, with the slogan Loyal to the Declaration of Independence, I am struck by this sudden display of fealty to a document that I do not even remember reading in school. In the absence of a constitution, Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence remains the only foundational document articulating civil rights in the state of Israel.

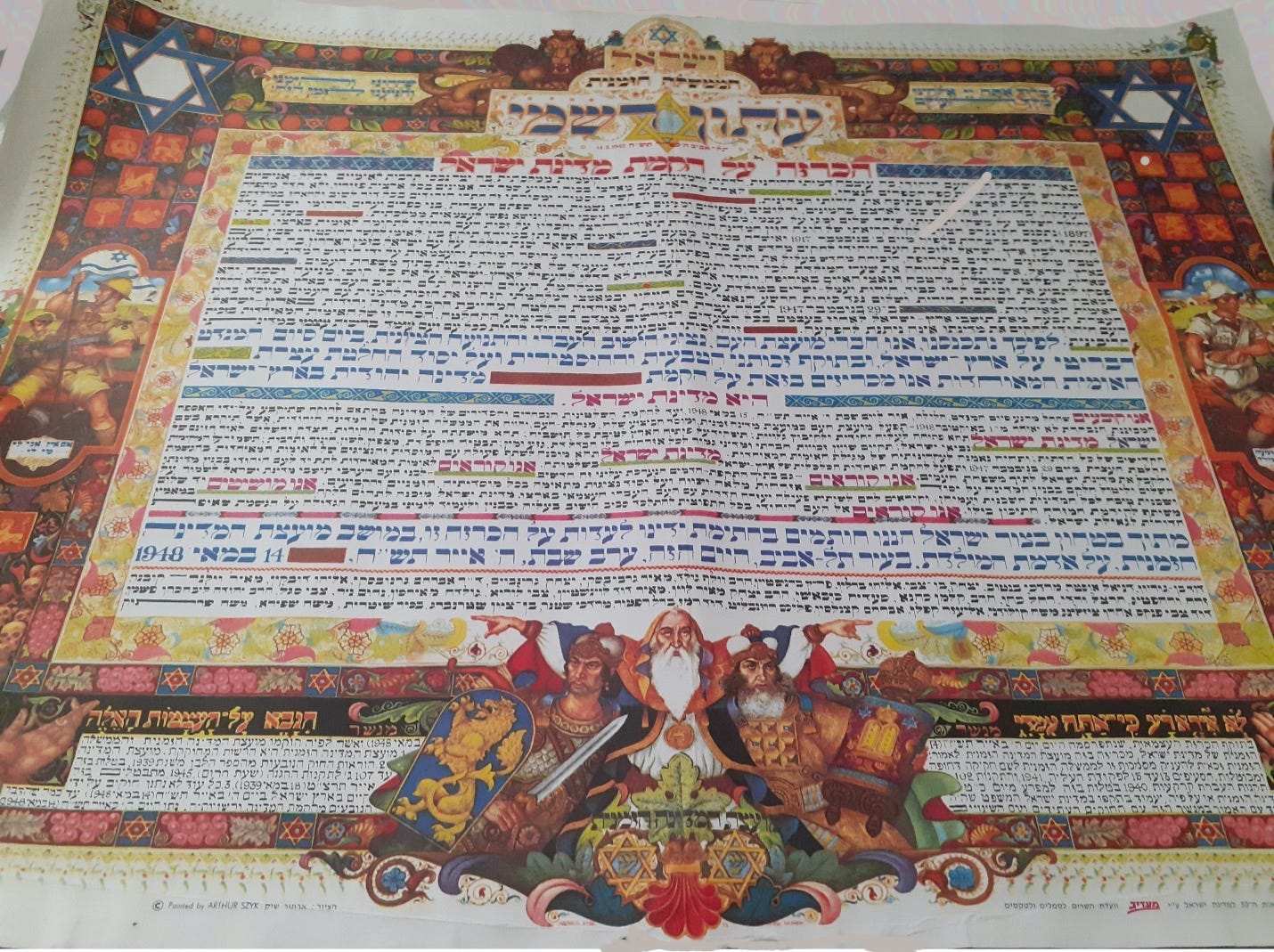

To my surprise and delight, on my last visit I discovered among my late mother’s belongings an ornate copy of the Declaration likely issued in 1948, the state’s contemporary. I realize that this artefact also rewards the classical historian’s treatment. The text is embellished with illustrations that would not have been out of place on an illuminated medieval manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. At the bottom center is a man with a flowing white beard (could be Moses), arms spread over two figures and fingers pointing at two biblical verses, I will fear no evil for thou are with me (Psalms 23:4) and prophecy upon these bones (Ezekiel 37:4). Below Moses is Aaron, the High Priest, in full regalia, carrying a scroll of the Torah and wearing a breastplate with twelve stones, representing Israel’s twelve tribes. On Moses’ other side is a medieval knight armed with a sword (likely Joshua; likely David). Two additional figures express 1948 perceptions of Israeli man—images of virility, fertilizing the land (on the right with a bucket of seeds) and defending it (on the left with gun and a flag). What is missing? Women of course. The mothers and grandmothers of the countless female protesters who flood the streets with me every Saturday. I hope that one day this beautiful document will be decorated afresh in the more egalitarian spirit these protests are summoning.

In spite of the benefits of studying history all my life, being a historian does not necessarily help a person respond to historic times. It may though help one to read them. The protests’ street literacy has created thousands of ad hoc historians fully aware that they themselves are making, and writing, history, before their own eyes.

Hagith Sivan is the author of Jewish Childhood in the Roman World and Galla Placidia: The Last Roman Empress, among other books.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Our most recent review, Michael Robbins on Wild Souls: a writer grows weary with writerly bromides in the face of crisis.

Detroit’s Source Booksellers is Book Post’s Autumn 2023 partner bookstore! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com. Read more about Source’s story in here in Book Post.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

If you liked this post, please share and tell the author with a “like.”