[Read Part One of this post here]

In mid-October, Rosenberg found Picasso and Olga a luxurious Right Bank apartment, and Picasso immediately asked his friend Apollinaire—with whom he had shared years of Montmartre grittiness—to come see it. Shortly after the visit, Apollinaire fell ill; by the first days of November he was coughing uncontrollably. Picasso was devastated—and terrified. A notorious hypochondriac, Picasso ordinarily stayed as far away from sick people as he could; during the pandemic he was known to hold his hand over his mouth when anyone spoke to him to guard against infection, a gesture that seems particularly resonant today. (The doctor’s article in Mercure, which Picasso may well have read, warned that flu patients must be totally isolated.)

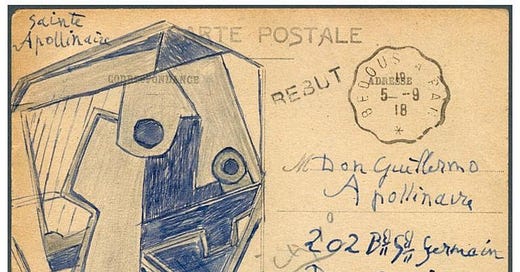

And yet Picasso was at Apollinaire’s bedside hours before he died. When a doctor was sent for, the poet said, “I want to live! I’ve still got so much to say!” That afternoon, Picasso was too upset to do anything except stare in the mirror and draw himself, over and over again. (“Self-portraitists usually look lonely,” his biographer John Richardson has written, “but few as lonely as Picasso does in these drawings.”) When they learned of Apollinaire’s death Picasso and Olga ran back to his apartment. Picasso, holding a lamp above him, commented that he looked just “as he was when we first met.” Above his bed, between two candles, hung the painting Picasso had given him that summer.

Help spread the news about books and ideas

Subscribe to our reviews: $5.99 for a month, $45 for a year

Building a connected world through reading

If Picasso had also contracted the flu, much of the art world we know today might not have come to pass. By 1918 he had already produced some of the most revolutionary art of our time. He had absorbed El Greco and Cézanne and the sculptural traditions of sub-Saharan Africa; he had taken Cubism to the cusp of abstraction and back again; he had made a cast of lonely circus performers, nudes, blind men, absinthe drinkers, and other castaways an enduring image of turn-of-the century bohemia. Yet much of his art—and the international renown that would secure his lasting influence—lay ahead of him. He was nearly twenty years away from Guernica, and even Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, painted back in 1907, remained in his possession, known mostly to his own circle in Paris. At the time of Apollinaire’s death, Picasso was largely shunned in the United States and knowledge of his work there confined to a handful of connoisseurs. As his French biographer Pierre Daix put it, he was still “a celebrated unknown.”

Picasso himself seemed to recognize the cruel arbitrariness of Apollinaire’s premature death and his own survival. For years to come, he obsessed over designs for a monument to his friend, a project that would inspire some of the most original sculpture of his career. Playfully conjuring modern machinery, West African kota masks, avian forms, and astronomical maps, these varying, spindly welded-wire prototypes attempted to give material form to Apollinaire’s polymorphous genius, creating what the poet had described in his novella, The Assassinated Poet, as a “statue made of nothing.” Ultimately, the designs were a little too radical, and, in an outcome that would have amused Apollinaire, the literary committee that was sponsoring the monument rejected them. (In the late fifties, skittish Paris officials would finally adapt an unrelated and rather conventional Picasso sculpture for a monument in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.)

As his own star rose and rose, Picasso could not forget his “cher Guillaume.” Even as he cycled through mistresses and wives and lived through another world war—even as he entered his ninth decade, more than fifty years later—he was still quoting from Alcools and striving to give form to its shattering vision of modern life. If the pandemic had robbed him of his greatest friend, it had also, as Read suggests, given him an enhanced sense of purpose, a kind of death-defying life force that would push him restlessly forward, year after year. It would be up to Picasso to consummate the poet’s leaping ambition and live out his evocation of self-replenishing genius:

Listen to me, I’m the throat of Paris

And if I want, I’ll drink the universe again

Hugh Eakin, a Brown Foundation Fellow, is working on a book about Picasso in America.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box, as well as free posts from time to time like this one. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Recent reviews: John Guare on Stephen Sondheim; Anthony Domestico on Louise Glück.

Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe, in Asheville, North Carolina, is Book Post’s Autumn 2020 partner bookstore! We support independent bookselling by linking to independent bookstores and bringing you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 there during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Book Post has done it again. This 2-part essay is sublime. The first had me thinking beyond my pandemic-limited life and on the edge of my seat waiting for the second part, the second part so beautifully conveyed the depth of human connection that is fundamental to all that is glorious in this world; and that is assaulted in the challenges we face right now. Thank you, Ann, for this wonderful project. -JCP