Diary: J. M. Coetzee, (2) Mother Tongue

Can a writer’ find his work beyond the boundaries of one language?

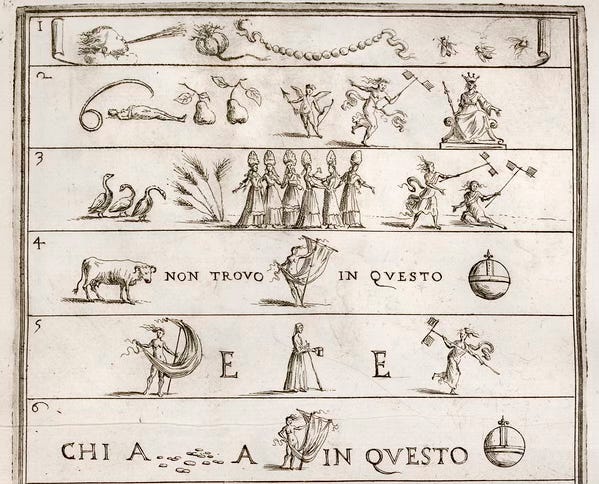

Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (1634–1718), Engraving with Rebus (detail). Istituto centrale per la grafica, Rome

Read Part One of this post here

In this way we come to my novel The Pole, which first saw the light of day in Buenos Aires in 2022, in the version that you prepared, and then in Australia in 2023, before making its appearance in the North. The English in which The Pole was composed is unusually bodiless and unlocated: it is not at all obvious where in the world it comes from (given that English is used as a medium for writing over much of the world today), and it lacks the solidity (semantic but sonic too) that characterizes most high-quality literary English.

There are two reasons why the book inhabits this null linguistic state. The first is that I deliberately starved it of what I think of as native nutriments while I was composing it. The second is that, by the time I began to compose it, I had reached a point in my life where I was seriously concerned about the English language as a global political force, and wished to emphasize my personal rupture with it.

It was my intention that no translation—no “good” translation—of the book should be inferior to the English, and thus that the notion of an “original” version of The Pole/El polaco could be brought into question. As legal copyright holder of the story, and therefore in a sense its “owner,” I intended that the English text, once it had metamorphosed into the Spanish text, would retire for a while, withdraw into the shadows, while the Spanish text would give birth to a multiplicity of translations.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.