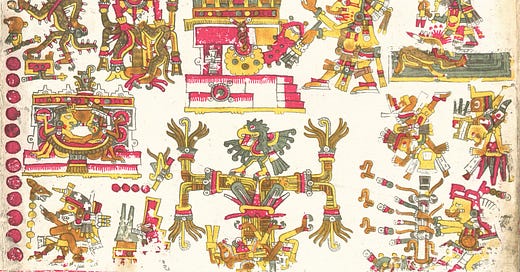

Cihuatlampa, “the place of women” in the western part of the sky, inhabited by women who die in childbirth according to Mexica cosmology. From the Codex Yohualli Ehecatl (Codex Borgia), a sixteenth-century manuscript from Central Mexico. Vatican Library

I’ve just read “The Third Baby’s the Easiest” by Shirley Jackson. A woman is on her way to the hospital to have her third child. Both the drive to the hospital and her labor are protracted, confused, complicated, and painful. The people around her keep insisting that she is “only having a baby,” and that the third is “the easiest.” My favorite part is when she gets to the hospital and the receptionist asks a series of tedious questions that she has to answer between contractions. When the woman inquires about her job, Jackson replies, “writer.” The receptionist says, “I’ll just put down housewife.” Despite her pain, Jackson repeatedly clarifies that she is a writer and the woman repeatedly says that she’s going to put down housewife.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.