Diary: Jeff Deutsch on Organizing Books, i.e., Ordaining the Universe

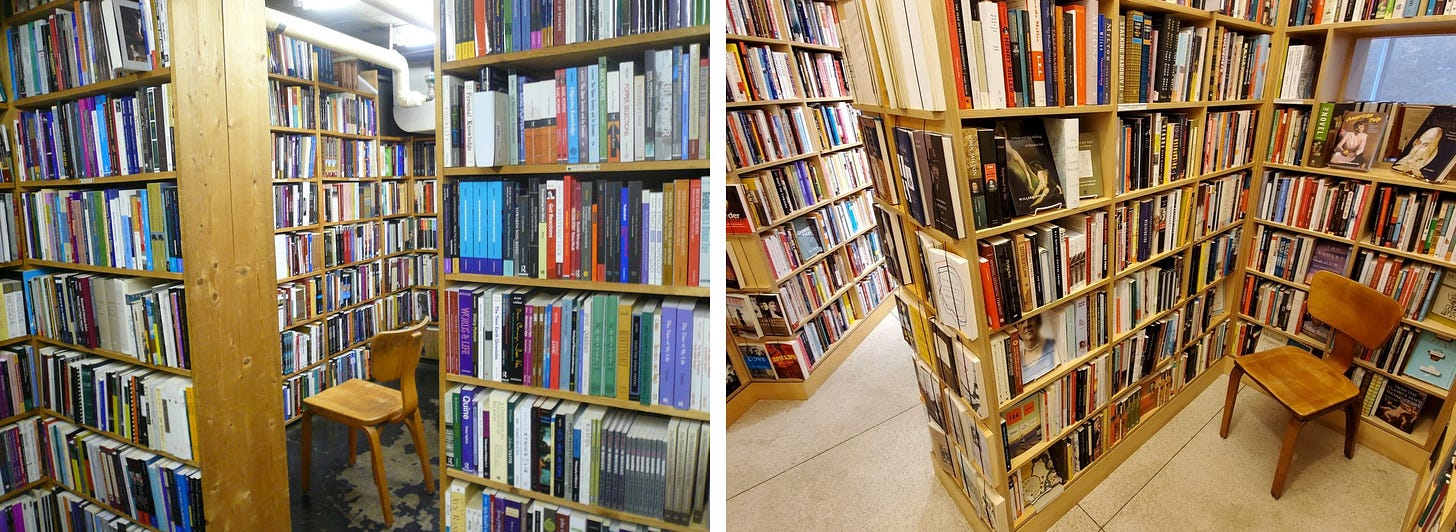

In the stacks at Seminary Co-op, then and now.

How a bookseller orders their collection dictates the logic and serendipities of a bookstore’s unique browse. Alberto Manguel tells us that the Sumerians called catalogers “ordainers of the universe.” Noting that our own bookstore, Seminary Co-op in Chicago, shelved books on the history of religion in the anthropology section, Indologist Wendy Doniger remarked, referring to the store’s then general manager Jack Cela, “all our efforts to keep the two disciplines separate had failed. If Jack saw that they were the same, they were the same.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.