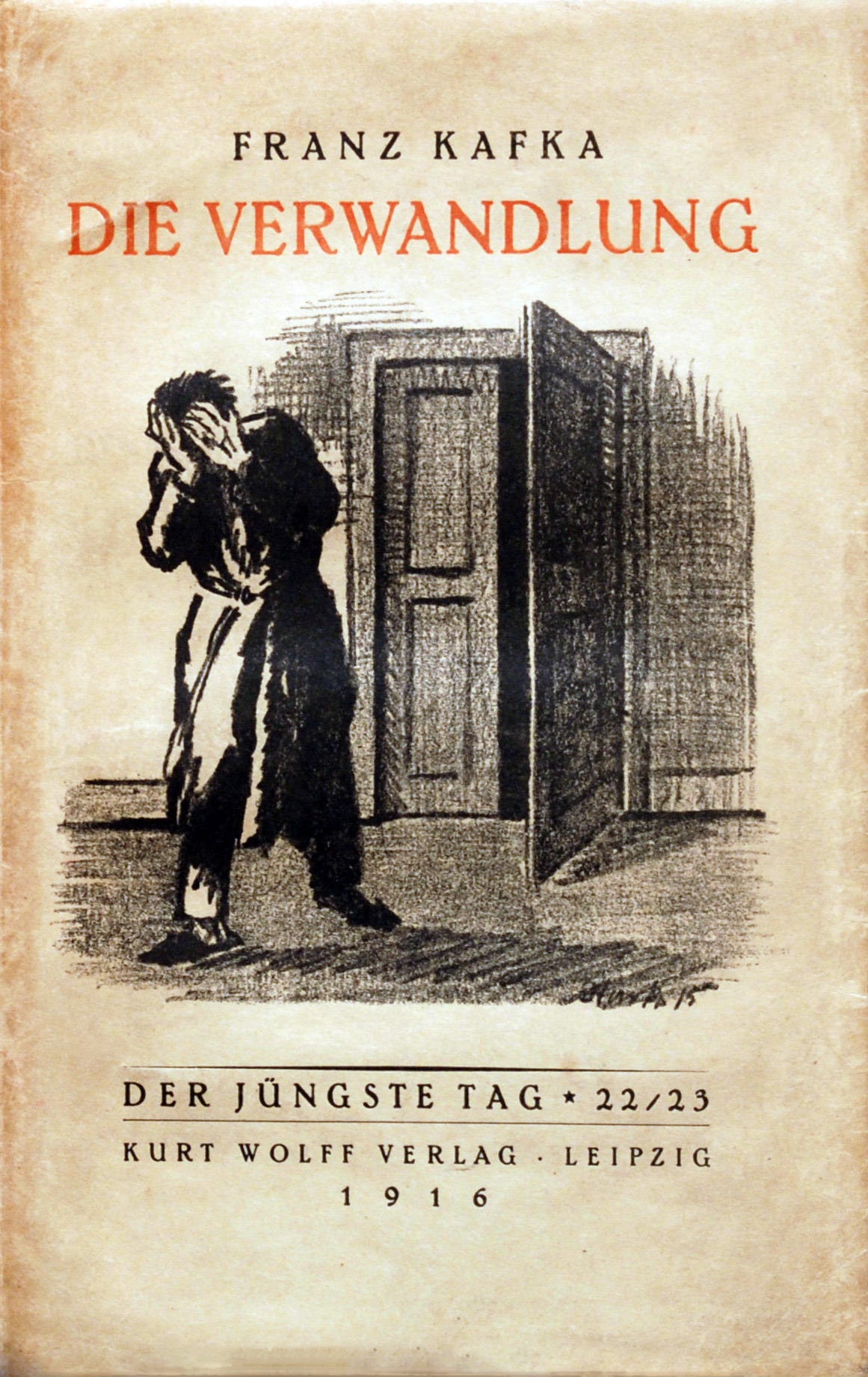

In a recent edition of Franz Kafka’s drawings, which are now being released for publication after long legal wrangling, editor Andreas Kilcher recounts the efforts of the original publisher of Kafka’s famous story “The Metamorphosis,” in which a salesman named Gregor Samsa awakens one morning to find himself transformed into a bug, to illustrate the story. The publisher, Kurt Wolff, later emigrated to the US and we wrote about his contribution to American letters last year.

Wolff had requested from Kafka the opportunity to read the narrative fragment “The Stoker,” which would become a part of Amerika, and “The Metamorphosis” on April 2, 1913, and by April 8 he had already responded with a concrete offer for “The Stoker,” while Kafka deliberated over sending “The Metamorphosis.” The typesetting, corrections, and printing of “The Stoker” were completed in short order: On May 25, 1913, Kafka was already writing to Wolff to thank him for sending his author copies of the book, which appeared as number three in the newly created series Der Jüngste Tag (Judgment Day). But his joy was tempered by an unwelcome surprise: a frontispiece with the caption “In the Harbor of New York.” It was clearly intended as an illustration of the first pages of Kafka’s text, in which the protagonist Karl Rossmann arrives in New York Harbor aboard an ocean steamer. Kafka objected to this in two respects, as he promptly wrote in his reply to Kurt Wolff: first, they had not agreed to have a frontispiece at all, and now he feared that the illustration might dominate the story; and second, what he himself had pictured was not a ferry arriving in a preindustrial harbor, but rather an ocean steamer arriving in the large harbor of a modern industrial metropolis. The letter remains polite, but it does not disguise Kafka’s displeasure. At the same time, though, Kafka forces himself to come to terms with the image and make it more palatable, at least to himself, in part through a surprising reference to their mutual friend, the artist Alfred Kubin:

Many thanks for the package. Of course I cannot venture to give a business judgment on Der Jüngste Tag, but in and for itself it strikes me as a splendid project.

When I saw the picture in my book, I was at first alarmed. For in the first place it refuted me, since I had after all presented the most up-to-date New York; in the second place, the picture had an advantage over my story since it produced its effect before my story did, and a picture is naturally more concentrated than prose; and thirdly, it was too pretty. If it were not an old print, it might almost be something of Kubin’s. By now however I have completely come to terms with it and am very glad that you surprised me, for had you put the matter to me, I would not have been able to agree and would have been robbed of this beautiful picture. I feel my book has been definitely enriched by the print and that already an exchange of strengths and weaknesses has taken place between picture and book. By the way, where did the print come from?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.