Diary: Kathryn Davis, On Walking

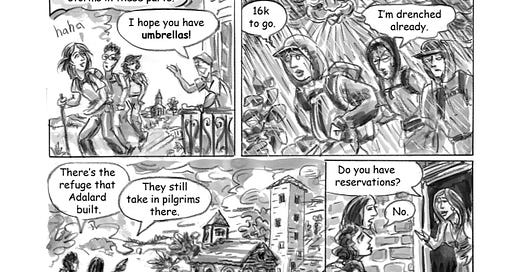

Image: From a graphic novel in progress, Walk this Way, by Sabrina Jones, about what a cartoonist learned on her way to Santiago

Several summers ago, I walked a section of the famous pilgrim trail that begins in a host of different places but always ends at Santiago de Compostela, home to the earthly remains of the apostle James. In France the trail is called le Chemin; together with my friends Steve and Sabrina, I started my walk in Le Puy, a volcanic landscape that also happens to be the lentil capitol of the world, and ended in the tiny village of Flaujac, where in the twenties my friend Sabrina’s artist grandparents built a small stone house, tucked into the edge of a giant hayfield in the Massif Central.

The desire to fill the empty space between one place and the next is overwhelming. It is, on the simplest level, what makes a person take another step on a trail, an impulse having less to do with the wish to see what’s next, what’s around that bend, over that rise, than with the imperative to make time contiguous. My friend Louise hates walking for this reason. She thinks it’s boring, unless there are stores, anything to disturb the horror of one day after another. The stores should be good ones, though. Also, the sidewalk should be smooth.

On le Chemin the trail underfoot was rarely smooth nor were there shops. There was the occasional village with its café or boulangerie. There was the occasional man or woman selling cool beverages in their dooryard. No one walking le Chemin was there to go shopping. Still, walking, there was the sense of a multitude of destinations, each of these destinations highly individual, some walkers approaching the walk as an expression of faith and in homage to St. James, some in a less specific yet decidedly spiritual vein, whether overtly religious or purely meditative, some because they wanted to exercise their limbs on a beautiful trail in a beautiful part of the world.

For my own part, I became intensely focused on my feet, on my splendid German hiking shoes (sadly quarantined each night with all the other hiking shoes to prevent the spread of bedbugs), on the mysterious relationship between the small distance covered with every step I took and the immeasurable distance inherent in the idea of destination—which is to say that over time, finally, I became intensely focused on just what a strange act walking is.

After his return from a more cosmopolitan period in Berlin to his home in Switzerland, the writer Robert Walser wrote more than fifty stories about walking. The longest of these, “The Walk,” composed in 1917, is considered a story, a piece of fiction, yet it’s obvious that the first person narrator, a writer, bears a striking resemblance to the author, particularly given the narrator’s strong identification with members of the class Walser was born into and in which we felt he belonged, the butchers and bakers and barbers and cobblers and tailors he encounters time and again while walking, who prove, time and again, to be nothing like the enemies of art he’s expecting but the bright spots on his journey. As the narrator explains in a lengthy “manifesto” that comes near the end of the story, “Walk … I definitely must, to invigorate myself and to maintain contact with the living world, without perceiving which I could not write the half of one more single word, or produce the tiniest poem in verse or prose. Without walking I would be dead …”

Walser spent the last thirty-six years of his life in mental institutions—though it’s not clear whether he ever had a genuine diagnosis. According to most accounts he was happy to enter the hospital in Berne, where he could do as he willed, “To be small and stay small,” as he put it, bearing out Virginia Woolf’s prediction that “If a writer were a free man and not a slave, if he could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work on his own feeling and not on convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style.” Later, though, when he was moved to a clinic in Herisau, Walser stopped writing completely. He died there, on a snow-filled path, on a walk, on Christmas Day, 1956.

I suppose it’s inevitable that stories about walking will conjure the endlessly unrolling “road of life”—in Walser’s case, despite the endless unrolling of the paragraphs, lists, and sentences that comprise “The Walk,” there are also many moments where the unrolling stops, some of them only for an instant, provoked by shifts in the narrator’s thought process (“Young boys and girls race around in the sunlight, free and unrestrained. ‘Let them be unrestrained as they are,’ I mused. ‘Age one day will terrify and bridle them. Only too soon, alas!’ A dog refreshes itself in the water of a fountain”).

To walk with this narrator is to keep company with Walser; it’s as if he desires your company in order to keep the unrolling from seeming endless but also from having it come to an end. Transition here is a form of invitation; the solitary walker either chooses his solitude or feels it thrust upon him. Spazieren (literally, to space) is German for take a walk.

In the case of Walser, whose self-described relation to the reader is one of “gentleness and tenderness,” solitude can be experienced as both blessing and curse, simultaneously.

The great single paragraph that constitutes Part 1 of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy (excepting the brief opening paragraph in which Molloy leaves his mother’s room) begins with him walking to find her. Destination is overt here but almost immediately overpowered by digression, everything dwindling, a town, a policeman, a violation of decency involving Molloy and his bicycle, corncrakes in flight, a hawthorne tree, mornings sunny “until ten o’clock or coming up on eleven … and in Molloy’s numbed heart a prick of misgiving, like one dying of cancer obliged to consult his dentist,” whilst approaching the ramparts of a town named X or B or P “when already all was fading, waves and particles, there could be no things but nameless things, no names but thingless names,” a dog with the name of Teddy belonging to someone named Lousse who buries him under a tree, and “It seemed to me if I kept on in a straight line I was bound to leave sooner or later,” between town and sea a swamp, and “if on the other hand it is true that regions gradually merge into one another, and this remains to be proved, then I may well have left mine many times, thinking I was still within it,” and into a forest where a charcoal burner offers to share his hut, “and if I did not go in a rigorously straight line with my system of going in a circle, at least I did not go in a circle, and that was something,” black slushy leaves, crawling on his belly, eating a mulberry, blowing his bicycle horn from time to time and the forest ends in a ditch, a “plain rolling away as far as the eye could see,” the towers and steeples of a town, and again he remembers the corncrakes, the sheep, rain then sunshine.

Sometimes these narrators appear to be walking to get somewhere but, more often than not, they prefer to be walking without a sense of destination. The thing about walking—about “taking a walk” as opposed to walking to get somewhere—is that the walker’s sense of purpose is tautologically just that: “to take a walk.” Whereas whatever we do with a sense of purpose reminds us of our mortality.

Walking meditation is a common Buddhist practice. In Japan it is called kinhin, meaning to go through like the thread on a loom, or (literally) to walk straight back and forth. Practitioners walk clockwise around the room while holding their hands in shashu, one hand cupping the other, which is closed in a fist. The pace can be fast or slow, the pace timed to coordinate with the breath.

“My steps were measured and calm,” Walser wrote, “and, as far as I know I presented, as I went on my way, a fairly dignified appearance.”

“In my head there are several windows, that I do know, but perhaps it is always the same one, open variously on the parading universe,” says Molloy. “The house was fixed, that is perhaps what I mean by these different rooms. House and garden were fixed, thanks to some unknown mechanism of compensation, and I, when I stayed still, as I did most of the time, was fixed too, and when I moved, from place to place, it was very slowly, as in a cage of time, as the saying is, in the jargon of the schools, and out of space too to be sure.”

To walk on a trail is to walk on a line. The line might go up or it might go down or it might bend right or it might bend left. It might even shoot you off in a different direction momentarily, into a moist, ill-lit chapel smelling of melted beeswax, or in a gite smelling of yeast and Gauloises. After awhile you might come upon a wayside cross practically invisible under all the blue plastic rosaries heaped upon it by the pilgrims who got there before you. The rosaries are the ones the bishop in the cathedral at Le Puy distributes to everyone who comes to be blessed by him before starting out. The rain has just stopped but water still drips off an overhanging tree onto the cross and the rosaries, making the blue plastic beads glisten like precious stones. Here you are. Here you are on this single, small point. But still you are walking on a line that goes on forever, carrying inside you an infinitude of space.

Walk all you want. Time cannot be made contiguous.

Kathryn Davis is the author of seven novels, most recently Duplex, which is, by the way, a current staff pick of our November partner bookseller, Left Bank Books. (Davis teaches around the corner at Washington University.) Her new novel, The Silk Road, will appear in March. Joy Williams has said of it: “The Silk Road concerns itself with nothing less than the workings of the great wheel of time and its terrifying promises of rebirth and forgetfulness. A mysterious and wonderstruck work.”

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing to your in box book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers, plus a few other treats, such as this one, for followers of our free updates and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Books and Books in Miami, Florida, and environs, is Book Post’s October partner bookstore.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Robert Walser