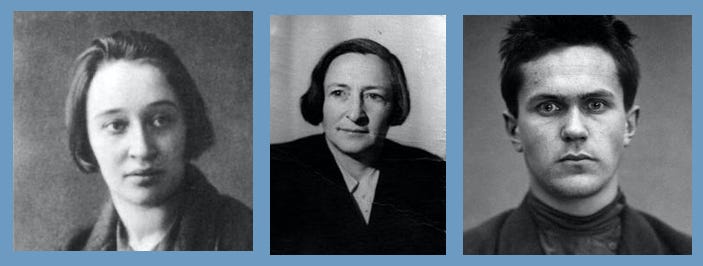

Nadezhda Mandelstam (1925), Lydia Ginsburg (1940), Varlam Shalamov (1929)

Poet Maria Stepanova writes of the Soviet-era memoirs of Nadezhda Mandelstam, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

As far as we can judge she set out to write a novel, something along the lines of a roman à clef, with real but disguised heroes. Perhaps this seemed safer at the time. “N. Ya. began her memoirs in the form of a novel in which all the names were invented,” wrote Larisa Glazunova, a friend in Tashkent whose family looked after her notebook labelled “material for the novel.” At the time the idea that the experiences of the twenties and thirties should be somehow drawn into a large-scale prose work, new, modernist, post-Joyce and post-Proust, but a novel still, a single form capable of holding everything together, hung in the air.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.