As part of the project, “Folkore Reimagined,” the British Academy asked Marina Warner to join their “Books That Made Me” series by selecting some books that have shaped her life and work and talking about them with broadcaster Ritula Shah. This post is adapted from their conversation.

I loved fairy tales as a little girl. My father was a bookseller, so I had extraordinary access to books, and in fact he was very indulgent father, so whenever my sister and I expressed an interest in anything, if we noticed a caterpillar, we would have a book about caterpillars come back from the shop the next day. So I was very spoiled in that way. Also there was absolutely no censorship, so I read my way through my grandparents’ library, which was full of derring-do and I’m afraid the most awful sort of imperial adventure stories, C. S. Forester, G. A. Henty, etc. I do think one has to remember that we’re also able to resist books—we can be made by them but we can also be in command of them to some extent. It’s quite important; I don’t think we should censor reading too much for children. I think we should let them make up their minds. I still have a great love of Kipling, for example, who is much criticized ideologically now. I was recently rereading the Just So Stories which of course are animal fables, a very long tradition in folklore, one of the most ancient, going back in India to the Panchatantra, which is full of these tales of animals passing down wisdom, which Kipling adapted with such imagination and vitality and humor.

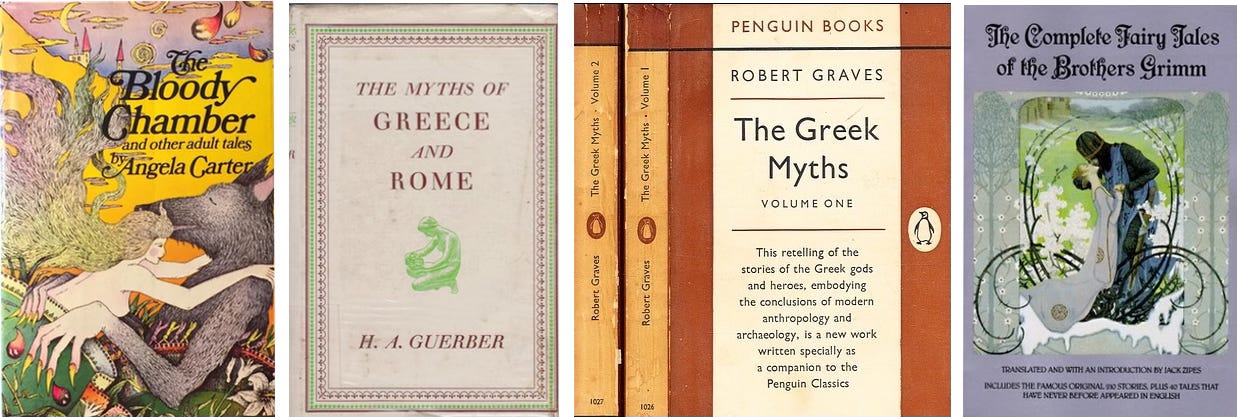

Fairy tales stayed with me in a sort of guilty-secret way—I knew that they were considered feminine, in fact not even feminine, they were considered girly, there hung around them a sort of miasma of suspicion, as if they were like pink dolls. I was of course a child before Barbie, I was spared Barbie, but there was a kind of feeling that fairy tales were in that genre. And then Angela Carter came along and she really released my generation from this sense of shame, so we can now love these stories. When she first broke into our imaginations with The Bloody Chamber she was a feminist, and it was a very feminist book, because she uncovered the latent erotic content and the kind of subversive and eerie quality of fairy tales. Then, the same year, she published her essay on desire, The Sadeian Woman, a very powerful essay, a very polemical, furious piece, and she became controversial for appearing to be sort of pro-pornography, considering pornography as revelatory of the transactional nature of marriage. The book came out of a period when she was very involved in French culture and surrealism, and surrealism was very interested in the sort of revolutionary power of violence, de Sade was one of their heroes. It’s a difficult essay now and also created difficulties for her during her lifetime. I’ve always stood up for her. I don’t think she’s colluding at all. I think she’s definitely on the side of the angels. She saw the difficulties herself: later she changed and a kind of Mother Goose figure takes over, the garrulous narrator in Nights at the Circus for example. She also put together a collection that was published originally as the Virago Book of Fairy Tales. I think it was two volumes originally but now it’s in one, called Angela Carter’s Book of Fairy Tales. It’s a very interesting collection because she selected without rewriting the stories and she shows a lot of the positive sides of this kind of material, the strength of girls and so on.

Read April Bernard in Book Post on Angela Carter

We differentiate fairy tales and folklore from myths because myths are really about gods, they demand allegiance and faith. We think of the Greek myths as mythical because we no longer worship them, but in Hinduism or in Islam there’s a lot of folklore that is believed, the jinn for example, who are the main motors of narrative plots and changes in The Arabian Nights. In The Odyssey, which is a famous myth, there is Circe changing men into pigs, an absolute classic center of many fairy tales, the sorceress–enchantress figure who is ravishing and lures you in and then does terrible things to you, changes you, perhaps not always into a pig, but certainly into other things. She wants to eat Hansel, and have Sleeping Beauty’s children cooked for her. There are other folklore elements not only in The Odyssey but in many myths. For example the trickster figure is common to myths and folklore. The trickster is a kind of hero who doesn’t occupy the same prominence as the warrior, the martial hero, or the saint hero of myth. The trickster is often an underdog who uses cunning to get by and to overcome the authorities—the giants, the tyrants, the kings. Odysseus is not an underdog but is nevertheless a trickster. In some of the stories that gathered around him, he’s quite a dubious character. There are many African tales about Anansi the spider, who is a trickster figure. It’s a definite character of worldwide imagination, unfolding the subterfuges and the ways that you can survive if you don’t actually have power.

Characterizing them as “mythic” was one of the ways of denigrating other religions from the Christian European point of view—you can’t say that the tenets of the Christian creed are fairy tales, nor should you say it about other religions either, because it carries such a pejorative charge, but I particularly loved the fairy tales that were taught to me in Catholicism—the stories of the saints, many extraordinary stories of saints flying, magicking away enemies, like Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a very famous saint who is able to turn her torturers from her, and Saint Christina, an even better story, in which her tongue is cut out by her father because her father wants her to marry a pagan prince and she doesn’t want to. He cuts out her tongue and her tongue lands on the ground and it flies up and pierces him through the eye. This follows very fairy-tale structure, but in the cathedral in Bolsena you can see the millstone in which they tried to drown Christina. It’s a perfect example of religion meeting folklore. I think now the liberalization of thought within the Christian churches means that they don’t bridle so much at the stories’ wonders, but allow some of these elements to be accepted as metaphors rather than literal events.

Read Marina Warner in Book Post on magical Christian women and folkloric crones as agents of resistance

The volume The Myths of Greece and Rome, which I had when I was a child, was illustrated with Victorian paintings, so for instance when I admired the Minotaur looking out over his terrace I didn’t really realize that he’s watching for the boat of Athenian boys and girls he’s going to eat. I just identified strongly with this solitary hulking figure looking so unhappy as he was gazing out to sea. I’m afraid that I liked Apollo and Daphne, I loved that story, and I would make my little sister play Daphne and then I would play Apollo and chase her around the garden. In The Myths of Greece and Rome that story is not seen as a rape; it ends with an explanation that it’s an allegory of how the dew is melted by the sun. I actually believe that it’s quite right to tell stories in a different way, I don’t think you should try to be authentic or accurate to some origin, because there is no known origin. Some people were brilliant at inventing stories, but Homer is a composite and many of these pre-Gutenberg, pre-printing press traveling stories were rewritten, readapted—and changed. Part of folklore’s nature is its inner transformations, even beginning often as written texts: there may have been written versions of some stories that were then elaborated on by oral means. I've always emphasized that there is a transmission from voice to page and from page to voice that goes on all the time.

I know these stories now because I was young and impressionable when I encountered them, the funny names didn’t seem funny to me. Some of the first names I came across seemed no stranger than, you know, Mr. McGregor. Actually as a child you’re very accepting of different things, it doesn’t strike you as strange, a blue beard is not particularly odd, and so on.

Robert Graves’s writing about myths caused a certain amount of controversy but for me his book The Greek Myths is a very learned compilation and extremely useful still. It is Greek, it isn’t Roman, so there are some very famous myths that you can’t find in it, which is quite frustrating, but he does some things which people now writing about myths or retelling myths don’t do. He gives you the sources, which is incredibly generous of him, so you can go back and actually look at what he’s drawing on, and then he winkles out his own interpretations which are very wacky and all to do with worshiping the goddess and all kinds of strange things, but he takes these ideas out of the story and puts them in another set of footnotes so you actually have a very honest volume. He’s a poet and he writes very well, you have these nicely retold stories, and where they came from, what he’s using, and then his own interpretation, which you’re free to accept or not. Later he became controversial for The White Goddess, which is a sort of feminist take, mostly on Celtic myth, but very much I think a male feminist take. There is a dilemma that I’ve been struggling with all my life, which is this deification of woman: it is not very helpful to women, because it separates them out, it distinguishes them from other concerns, it doesn’t let them be, doesn’t let us be real. There was a whole group, some of them marvelous writers. Ted Hughes is another. I really admire Ted Hughes, he was a marvelous poet, but he had this goddess-worshipping side. In Ted Hughes’s case, and possibly in Robert Graves’s too, it contains a streak of a kind of violence. But I’m more interested in this approach now than I used to be, because it’s come back so strongly, goddess worship. I have letters and emails from many young women artists and poets working with this material. There’s a real resurgence of the desire to find a feminine spiritual principle. At first I was worried about it, because I thought we were getting back onto the territory of The White Goddess and the idea that somehow menstruation and biology made women very different and very special. It may be I was wrong; there is certainly an evolution going on now which is more interested in feminine difference.

I do think though that fairy tales have been misrepresented or mis-selected to emphasize stories of male courage and female passivity, because if you begin to read widely in them actually there are a lot of plucky girls, some of them even tricksterish, so they outwit the giant or the enemy or the tyrant or the suitor whom they don’t want, and others are simply brave and courageous. Hans Christian Andersen took that type when he made Gerda in “The Snow Queen,” which is a wonderful fairy tale and an example of a literary reworking of lots of motifs from traditional fairy tales. It’s Gerda who goes out to find Kay after Kay has been stolen by the Snow Queen.

Read Kathryn Davis in Book Post on Hans Christian Andersen and childhood

The Grimm brothers claimed to have collected from the people, their project was part of the Romantic movement, which also brought us Wordsworth and Coleridge. Their Lyrical Ballads are in a sense invoking the oral tradition of the British Isles. Coleridge, even more than Wordsworth, was influenced by the German Romantic movement, which was led by a whole group of people who at first collected music, they collected ballads, like Des Knaben Wunderhorn, “the young man’s wonderful horn,” which was the first Romantic collection of popular songs. It contains stories, a lot of them very eerie, like “The Erl King,” which we know from Schubert’s terrifying setting, the Erl King being the spirit of the forest who steals children. The Grimms did travel around, but they didn’t actually collect from as many peasants and workers as they said. They had a whole extended family with connections to France, and they were very distressed to discover that some of the fairy stories in their first collection were French. Theirs was a very nationalist movement, a way of getting away from classical culture, from the gods of Greece and the whole Hellenistic passion of the eighteenth century. They were trying to go for the local, the folkish, the echt imagination of the people.

This movement did actually preserve a lot of material that would have been lost, but it was interesting that the Grimms didn’t really find as much authentically German popular material as they hoped. And they rewrote a lot because they were very censorious. They were not worried by the violence in fairy tales, they didn’t mind how many people were torn in two or, you know, danced in their red-hot shoes till they dropped, but they did mind sex, they were extremely prudish about sex. In the famous story of Rapunzel, you remember, she is shut up in a tower by her adopted mother, the grandmother figure, and isn’t allowed to see anyone, but then a prince notices that the old woman climbs up her hair to get into the tower so he does the same thing, and then a few months later, in the original, Rapunzel says to her grandmother, “why are my clothes getting so tight?” and the old woman becomes absolutely furious. The Grimms changed this, because they didn’t want the idea that Rapunzel had had sex with the prince.

So in the original story, as opposed to the Grimms’ retelling of it, there would have been what we should assume to have been some sort of message or idea behind it: the stories were told as forms of passing on wisdom, this was very much mother-wit. They contain huge amounts of sex education. This was perfect storytelling: this is what happens if you let a prince climb up your hair, don’t let your hair down for anybody. There are many other examples. My favorite is “Donkeyskin,” which is actually a story by Charles Perrault but has many counterparts in other collections. There’s an Italian one and earlier, medieval versions. The father loses his wife, she dies, and she makes him promise that he will never marry anyone who’s not as beautiful and as good as she is, and then their daughter grows up and, you know, he says gosh, she’s just as beautiful and good as her mother was, and so he wants to marry her, and the daughter runs away with the help of a fairy and she disguises herself in a donkey skin. The story really does pass on the idea that she is right to run away. That’s a deep lesson about child abuse and protecting yourself, but it’s told in such a way that it doesn’t tell you that the man next door or your father might be a threat to you—it kind of tells it in a in a way that I think is very sensitive to children, because it passes this on without necessarily alarming them.

Subscribers can read Part Two of this post here.

Marina Warner’s most recent book, Sanctuary: Ways of Telling, Ways of Dwelling, was published this month in the UK. It considers sanctuary as an ancient right and a sacred prohibition, explores the concept of hospitality, the imagination of place and travel, and asks, could a revived practice of sanctuary help to define ideas safety, home, freedom of movement, and peace in a world increasingly riven by displacement? She has also been working with the project Stories in Transit, which brings young refugees together with artists, writers, and musicians in the UK and in Sicily to invent or reimagine stories and perform them. The work offers storytelling as “a salve, a route to a site of mutual interaction and understanding, and a new place of belonging and conviviality.” In October her exhibition, The Shelter of Stories: Ways of Telling, Ways of Dwelling, will open at Compton Verney, in Warwickshire.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Some Book Post writers: Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, Jamaica Kincaid, Lawrence Jackson, John Banville, Álvaro Enrigue, Nicholson Baker, Kim Ghattis, Michael Robbins, more.

Page & Palette in Fairhope, Alabama, is Book Post’s Summer 2025 bookselling partner! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

Thank you so much for this article. It opened so many new horizons and directions, what to explore and what to pay attention to.