Diary: Noga Arikha, Stories and Neurology

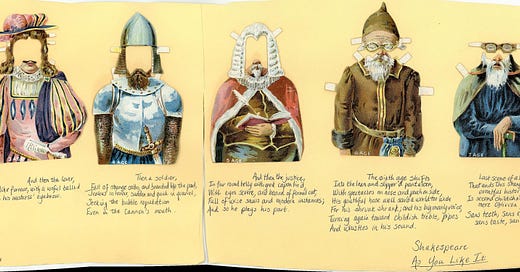

We know that without the sense of temporality embedded within memory, there would be no unitary self, and many emotions dependent on representing what is not immediately present to the mind would not exist—hope, anxiety, regret, pride, sadness, joy, love, guilt. Yet change is embedded within the very current of a unitary, subjective life. We have that “core self” that we feel to be so strong, for instance, in a loved one with dementia. We build an identity through time that is also outside us: things age, and we age in time, all things relative to each other. Being is being in time, in each others’ time. We change and experience time, in time, and especially in shared space and time. The cases of people with neurological damage who lose their connection to time—for example from dementia or amnesia—illustrate the ways in which metaphysics and biology connect. And our biology may give us the key to the metaphysics.

Start with the assumption that, if all is well, we awake each morning aware of being the person we were the day before. Personal identity seems, according to this standard view, to rely on temporal continuity, and the two, as John Locke had described in his “Essay Concerning Human Understanding” in 1690, are deeply connected. Of course, we also change—and this is what complicates the notion of personal identity. For Hume, writing a few decades later in the Treatise of Human Nature, “man is a bundle or collection of different perceptions which succeed one another with an inconceivable rapidity and are in perpetual flux and movement.” Just as flux characterizes our experience, so it is inherent in our identity: a small oak is the same tree as the grown oak, he writes, and the “infant becomes a man, and is sometimes fat, sometimes lean, without any change in his identity.” What binds the self together, the “source of personal identity,” is memory. “Had we no memory, we never should have any notion of causation, nor consequently of that chain of causes and effects, which constitute our self or person.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.