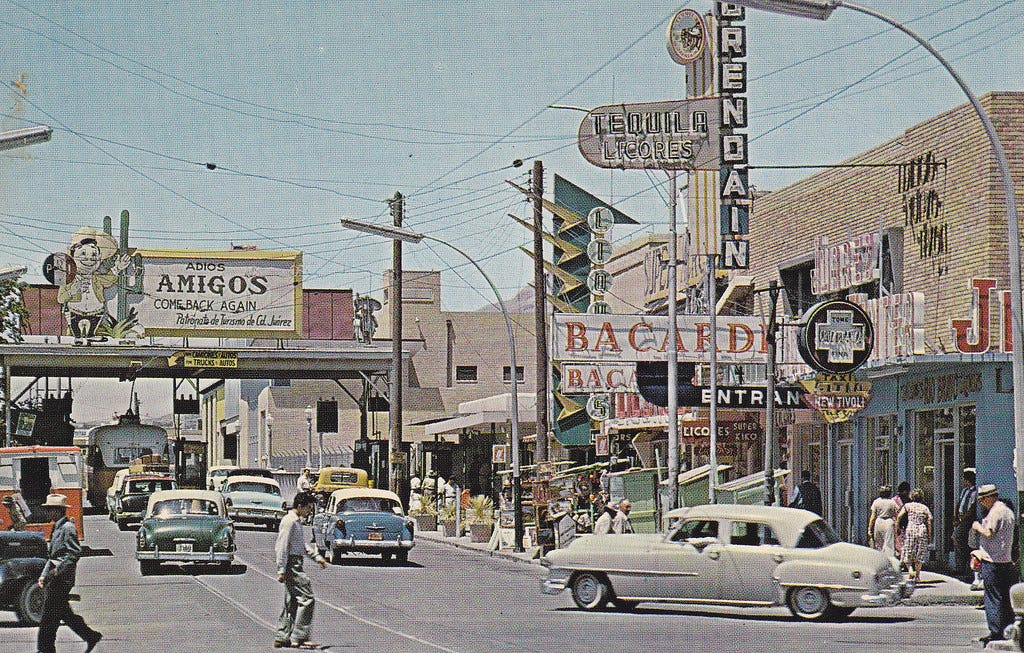

Playwright Octavio Solis grew up just a few miles from the Mexican border in El Paso, Texas. Join him as he remembers his Saturday visits with his family to neighboring Juárez.

Listen to that. That’s Juárez you hear. That is where we are once a month on Saturdays. Riding along la Avenida de las Américas with that crazed accordion erupting from the radios all around. Paleteros taking their smoke break on the curb. There’s the old cop who watches over our parked station wagon for a modest ten-dollar mordida from my dad. He’s got a gold tooth in his smile and duct tape around the handle of his gun. His armpits wet and ripe with his morning smell but it’s all a morning smell here. There’s the Centro Pronaf where we do our shopping, my mom filling her cart with things half the cost of those at our Piggly Wiggly. Plus the tortillas are always better here, chamacos. A short walk through the mercado, where the old woman sits on a stool hawking the leather belts in her leather hands, and the piñatas dangle from the ceiling like papier-mâché gods, and piles and piles of serapes and blankets amid black velvet paintings of Jesus and Pancho Villa and the Beatles. And the taquitos are fresh here. Sit outside and eat some with a Fanta while Dad throws a few centavos on the street to delight the urchins with feet hard as stone, and that little one looks like someone he remembers, maybe himself as a boy, and he gives him a half-dollar coin more. Poverty is obvious in Juárez; it’s out in the open, tugging on our sleeves, thronging around us for whatever surplus scraps of hope we’ve got. Now it’s time to see the barbers. My younger brother and I, and my youngest brother too, we’re all trying to cultivate styles that suit the time and we take pains to instruct the barbers how we want it cut, un poquito longer on the sides and the back, shorter on top, and can you make sideburns on us too like in those music shows on TV and the album covers of the bands we love, long hair is the way to go, por favor, and they nod like they understand, like they’re on our side, slapping their barber capes over us, spinning our chairs around so we don’t face the mirror, and then it’s all a chaos of clippers and trimmers and shears, our chins pushed into our sternums so all we see is our tufts wafting to the floor in clumps. We’re sobbing like fools when we finally see our scrawny bald heads in the pinche mirror, my father looking up from his Memín Pingüín comic book to find us wailing while those perfidious barbers sweep the frazzle-ends of our yearning into a fuzzy little mound for the trash bin. Dad pays them for their trouble and appeases us with some Mexican Coke, but it’s scant comfort, we’re so disgusted at how four-sided we look, plus that one with the pompadour left nicks on my neck and even nipped my ear, but Dad salutes us ’cause we look like Ft. Bliss soldiers, making us bawl even more; the world is over as far as we’re concerned. That’s when Mom takes over. While my dad tanks up the station wagon for five bucks, she takes us by the hands and guides us just a few steps down the buckling walkway past the bony dog dozing under his halo of flies through the open door of a warehouse so we can behold in its dark metal swelter this astounding vision: a young man thin and shirtless, spearing a long hollow pole into a kind of furnace and taking out a glowing mass of molten red-orange light, hissing against the cooling air, pieces of it spattering on the cement floor like lava. Then he performs this magic: he blows into the pole and the glob swells as he spins it over a flame, shapes it with another metal rod into something unimaginable, shapes it into glass, it’s glass he’s breathing, crafting it into forms that begin to take on color and character; it’s a vase, then a panther, then a long lamp-like sculpture, wondrous and ghostly, this gleaming young Vulcan breathing structure into throbbing suns of incandescent glass. Now we’re not thinking haircuts or sodas or feeling anything but the lulling heat of this primeval forge where the most elegant fragile fires are blown into being. All the way home, on the slow bumper-to-dented-bumper drive over the bridge back to El Paso, as we shove chili-powdered chicharrones into our mouths, we marvel at the genius of Saturday, ay sábado, mi sábado, you took our hair and paid us back with a glimpse at how this beautiful messy world blazed when it was first created, might blaze again someday.

Octavio Solis is a playwright whose work has been performed at the Mark Taper Forum in Los Angeles, the California Shakespeare Theatre, Yale Repertory Theatre, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and other venues nationwide. “Saturdays in Juárez” (under the title “Saturday”) will appear in his first book of prose, Retablos: Stories from a Life Lived Along the Border, a book of memoirs of his life growing up a few miles from the Rio Grande in El Paso, Texas, coming in October from City Lights Books (a legendary bookstore that is also a great publishing house!). The retablo is a centuries-old tradition in Mexican folk art: modest religious offerings painted on repurposed metal, telling the story of a crisis and offering thanks for its successful resolution.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing to your in box book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers, plus a few other treats, such as this one, for our followers and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable environment for writers and readers and to support bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land.

The Regulator Bookshop in Durham, North Carolina, is currently Book Post’s featured bookstore. Send them your good wishes as they gird themselves for Hurricane Florence! We will keep you posted on their fate.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Nice, well done!