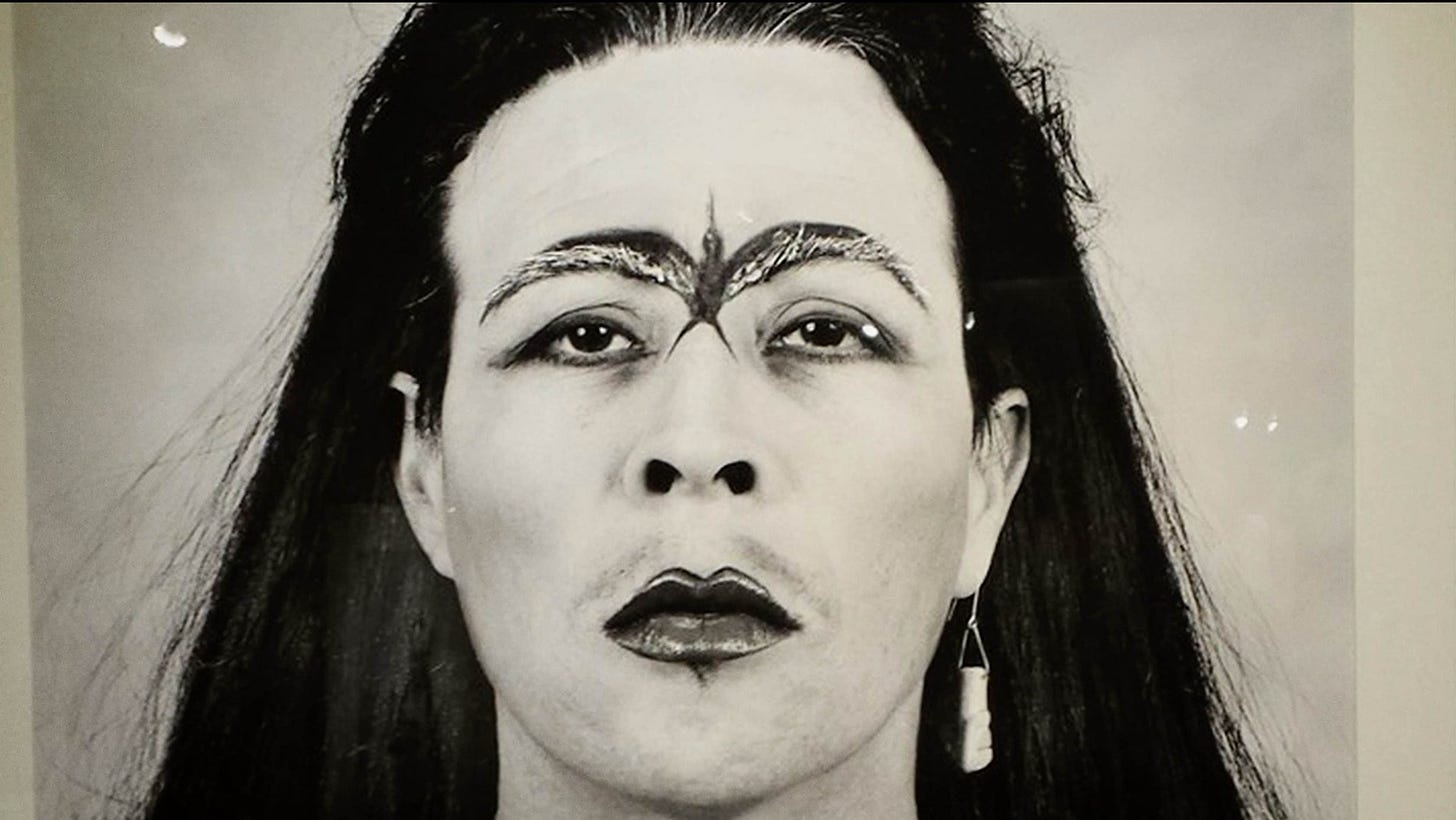

Still from the 2019 film Lemebel ©Joanna Reposi Garibaldi

El Coordinador Cultural

If I don’t tell the story here, it might get lost, as memory twists and closes like an oyster around remember when. Because the eighties had barely begun, and those days were so grim and blighted there was almost no light, and only a few of us voiced our outrage in public, through demonstrations that tried to wake the Chilean people from their sleepwalking, their consciences struck dumb by marching boots. Here and there, in disguise or on the down-low, actors, painters, poets, and political groups would meet up after curfew to plan acts of sedition against the regime. And that’s how El Coordinador Cultural was born—a ragtag committee of activists and artists who staged interventions on politically symbolic days. I think it must have been for September 11, as by sunrise the streets were already policed, just like every year, ready for any hint of protest. The organizers had met beforehand, in an unknown location to make sure the details weren’t leaked, which meant the exact time and place where we would intervene were kept secret until the last possible moment, the instructions passing only mouth to mouth to avoid using the phone or writing anything down.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.