Dear Summer Readers of Book Post:

I will be assuming that you have access to the full texts of these poems by Elizabeth Bishop, so my quotations will be relatively sparse. This week, I’ll be looking at “The Map,” “Over 2000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,” and “At the Fishhouses,” all of which have close connections to Bishop’s early life.

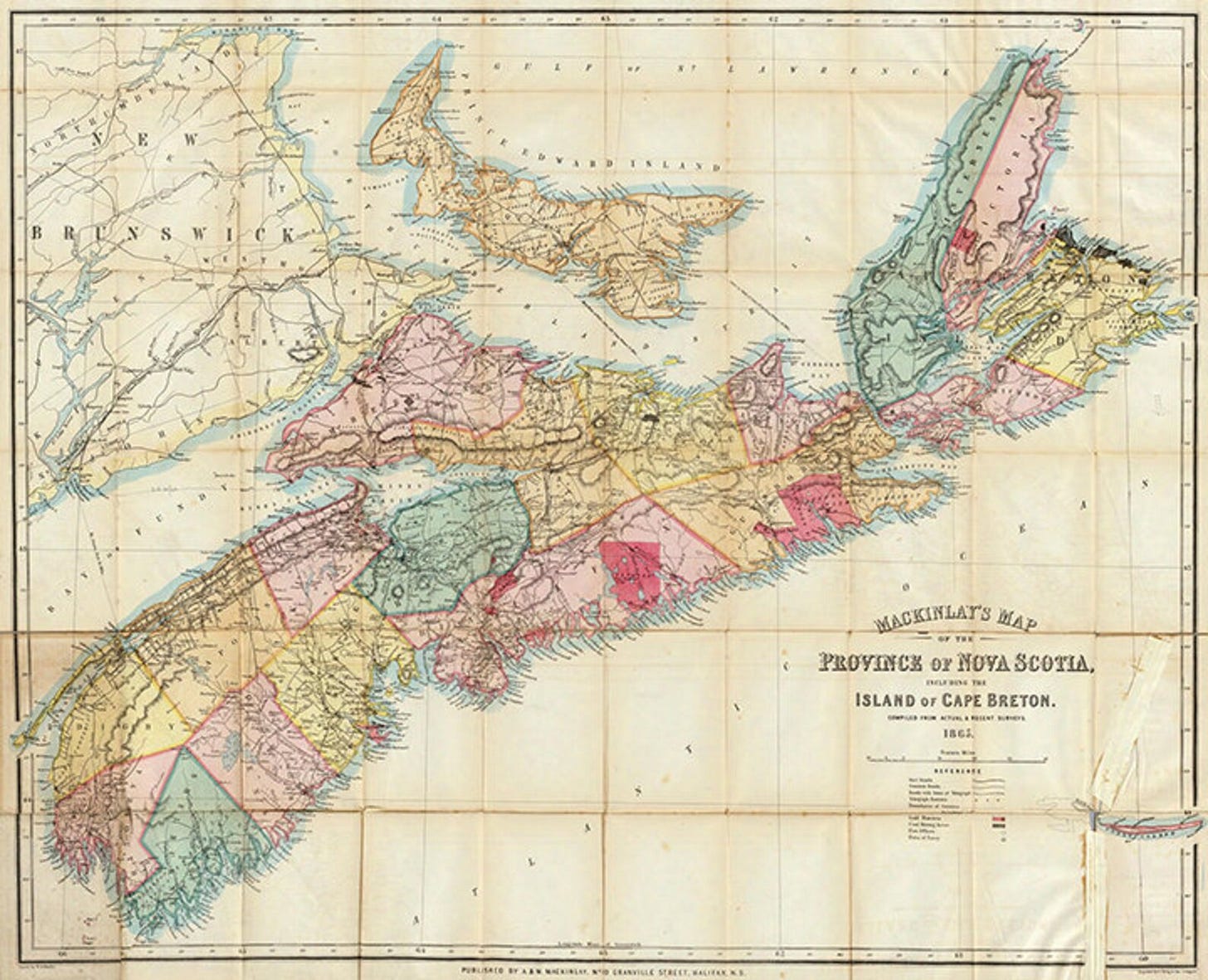

To begin at the beginning, “The Map” opens Elizabeth Bishop’s first collection, North & South; she speaks to us here, as she always will, in low, confiding tones—as a friend, perhaps. She is showing us something, a map of Eastern Canada and the Arctic, and has placed herself side-by-side with the reader to point out what she has noticed. Perhaps we are sitting next to one another on a couch, or on chairs drawn up to a table, with the map spread out before us. Aren’t maps interesting? is the implicit (and slightly familiar, even parental or pedagogical) question, rhetorical of course, because the poem’s task is to make them so.

The map includes the large peninsula of Nova Scotia. Although not stated here, it was the poet’s home, where she spent a significant part of her childhood being raised by her maternal grandparents. Though her father died when she was a baby, and her mother was placed permanently in a sanitarium when Bishop was five, these dramas of youth are entirely absent from the overt concerns of the poem.

Childlike, we inspect the map and marvel at its exact contours: “The names of seashore towns run out to sea, / the name of cities cross the neighboring mountains.” Periodically, the speaker hesitates, asking, as if in real time, whether her perceptions have been exact. “Shadows, or are they shallows, at its edges.” Although a fair number of Bishop’s early poems play with more regular forms, this poem is in a loose free verse of four-beat lines, irregulary rhymed, with an underlying cadence, often anapestic or paeonic, da-da-DUM or da-da-da-DUM. The effect of this is to create a gentle sort of wave action throughout, as in the lines, “Along the fine tan sandy shelf, / is the land tugging at the sea from under?”

When the poem ends, on its soft note—“More delicate than the historians’ are the map-makers’ colors”—we need a moment to reflect on what is actually being said by not being said. What might be the indelicate colors of the historian? Red for blood, to be sure, and other vibrant colors of strife and suffering. We are invited to see the map, in its softer pastels, as a kind of respite from history, although history made the map. Geography, this poem suggests, can offer a different dimension, or even alter time.

This opening poem displays several characteristics of Bishop’s lifelong poetics: A confiding tone; the impression that the poem is proceeding in the present tense, in real time, so that the speaker may correct herself or question her assertions; precision of physical detail; and a preoccupation with geography, and travel, that dramatizes a search for home both internal and external.

“Over 2000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance,” which was included in Bishop’s second collection (A Cold Spring), makes many of these same preoccupations even more explicit. John Ashbery said that this was his favorite poem of the twentieth century, and something of its rhetorical power can be seen, I think, as influencing his work.

Here, again, the speaker is asking us to sit alongside her and look at—not one map, but an old-fashioned historical and geographical atlas of some kind, as indicated in the title. Probably it was her favorite book in childhood, where she once traveled in her imagination. “The Seven Wonders of the World are tired / and a touch familiar, but the other scenes, / innumerable, though equally sad and still, are foreign.” This poem also asks multiple unanswerable questions—Have I visited the right places? Where should I have gone instead? What is travel for?—that establish the central drama of the poem as a crisis of belonging.

Although Bishop can also be quite plain-spoken, this is often cited as one of her “difficult” poems—perhaps because the narrator moves between images from the atlas and quickly sequenced images from her own disparate travels, without always letting us know which is which. “And at Volubilis there were beautiful poppies / splitting the mosaics; the fat old guide made eyes. / In Dingle harbor a golden length of evening/the rotting hulks held up their dripping plush. / The Englishwoman poured tea, informing us/that the Duchess was going to have a baby.”

In exasperation at the dizzying pileup of travels, the narrator breaks into the famous ending of the poem:

Everything only connected by “and” and “and.”

Open the book. (The gilt rubs off the edges

of the pages and pollinates the fingertips.)

Open the heavy book. Why couldn’t we have seen

this old Nativity while we were at it?

—the dark ajar, the rocks breaking with light,

an undisturbed, unbreathing flame,

colorless, sparkless, freely fed on straw,

and, lulled within, a family with pets,

—and looked and looked our infant sight away.

The manger scene of Christ’s birth in the stable becomes a locus of longing—for the childhood vision of “a family with pets,” for a childhood that might have been this beautiful, for a journey through the world where an exile might have found a home.

The “pollination” of the fingertips by the gilt on the pages is not only a perfectly exact image; it also links the gilded, haloed, divinely lit vision of the Nativity with both pollen dust from all the flowers mentioned earlier in the poem—“butter-and-eggs,” “Easter lilies,” “poppies”—and the sand and dust from desert scenes, in North Africa and elsewhere, in the poem. “Everything only connected by ‘and’ and ‘and’ ” may refer as well to the dissolving, dispersing act of time and weather on things that once seemed solid but which memory can only inadequately form.

If you haven’t read it recently, I urge you to look up Ashbery’s vivid—and, by contrast, exuberantly hilarious—poem, “The Instruction Manual,” in which a speaker in a boring office job takes a daydreaming journey to Mexico. “Guadalajara! City of rose-colored flowers! / City I wanted most to see, and most did not see, in Mexico!”

An adult visit to a Nova Scotia childhood setting, in which the poet leads us by the hand into a landscape, is “At the Fishhouses.” We first look down, with the speaker, from a slight height to take in the scene—“All is silver: the heavy surface of the sea, / swelling slowly as if considering spilling over” and the five fishhouses, an old fisherman, fish tubs, lobster pots, the trees—before making our way downward, and then pausing. “The old man accepts a Lucky Strike. / He was a friend of my grandfather.” Then we proceed, down the boat ramp to the water itself, where, our narrator tells us, she often encounters a seal, to whom she sings “Baptist hymns” because they both believe “in total immersion.

We have swooped now, slowly down, and down, and are on our knees, as the poet urges us into the water, telling us, “If you should dip your hand in, / your wrist would ache immediately, / your bones would begin to ache and your hand would burn / as if the water were a transmutation of fire.”

She ends by claiming that the salt water is

like what we imagine knowledge to be:

dark, salt, clear, moving, utterly free,

drawn from the cold hard mouth of the

of the world, drawn from the rocky breasts

forever, flowing and drawn, and since

our knowledge is historical, flowing, and flown.

So this story is not only of return to a childhood place, but also to a site of baptism, and to a “mother,” whose breasts are the stones and whose milk is the ocean. One of the many things I admire about this poem—apart from the gorgeous accuracy of detail—is that sonic pairing of “flowing, and flown.” As is often the case in the poems of George Herbert and Gerard Manley Hopkins, which Bishop read and studied, the music of language can make a “sense” beyond simple definitions or etymologies. And here, as in many other poems by Bishop, the ending sends us off, as if we’ve been dunked into the water for our own transformation, our own baptism, and perhaps our own death, into the cold “element” that is thrillingly, and maybe terribly, our true home. Her confiding voice here whispers us into the deep.

I am grateful to a reader who pointed out, after reading last week’s post, that Nova Scotia is not an island; it is actually a peninsula, connected to the mainland by an isthmus; its sister landmasses, Cape Breton Island and Prince Edward Island, are true islands.

Key West poems for next week: “Little Exercise,” “The Fish,” “Roosters”

Join the conversation in our comments below! Subscribe to our free posts to receive Summer Reading by email.

April Bernard is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently The World Behind the World. She is also author of the novels Pirate Jenny and Miss Fuller. She has written for Book Post on Colette, Elizabeth Hardwick, Hilary Mantel, Patricia Highsmith, Wallace Stevens, Janet Malcolm, and Angela Carter, among others.

Order Elizabeth Bishop’s Poems from Book Post bookselling partner Northshire Bookstore.

Join April and Book Post editor Ann Kjellberg in a virtual conversation looking back on our month of Bishop, hosted by our bookselling partner Northshire, on August 29 at 6 pm. Sign up here.

We are in the midst of a special summer offer on subscriptions to Book Post! Find out more here.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. “Summer Reading” is a special Book Post feature. You can join or check out of Summer Reading in your account settings.

Book Post aspires to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Coming soon: new posts from Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, who has spent years thinking about comedy, on the women of Hacks; Yasmine El Rashidi on the recurrent device in Arabic writing of the memoir trouvé; Kathryn Davis on a lingering childhood fascination.

Northshire Bookstore in Manchester, Vermont, and Saratoga Springs, New York, is Book Post’s Summer 2024 partner bookstore! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. Read our portrait of Northshire here. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Not ready for a paid subscription to Book Post? Show your appreciation with a tip

I'm very moved by something Mary Jo Kietzman wrote in her comment: "This line for me is an admission of somehow not being able to feel the sacredness of ordinary things." (Mary Jo was referring to the ending of "2,000 Illustrations" and, tangentially, also "Fishhouses.")

I have loved Bishop for decades; she was my gateway into writing poems. And the first thing I loved --that so MANY people love-- was her ability to capture the places and people she encountered. With her signature perfection and quirkiness. However, I don't think I every fully considered the distance she may have felt, not just from the idea of home and love, but from the very illumination and significance of the objects (or places) she describes.

Bishop created a quasi-holiness in the world for me. Mary Jo, with one simple sentence you made me feel how often Bishop may have yearned for that experience herself, but instead felt distance or dislocation. It make me think of what Dickinson says in #348: "Had I the Art to stun myself / with Bolts -- of Melody!".

Having returned a week ago from a week exploring Nova Scotia, this was perfectly timed. I’m transported back to brief experiences that left an indelible impression in my life. The Bay of Fundy’s 58 ft tide change is a life moment that begs poetry for expression. And the people — pure, undaunted, warm without coddling. There are occasional caution signs but they read very differently than those in the US — “Site seers have been rewarded here with death. Due to conditions, rescue is unlikely.”

Nothing else — no “be safe” or “be cautious.” Just the facts and we’re left to draw our own adult conclusions. There is something wonderful about that.