Guest Notebook: Back to School special! (1) A little history of American math books

by Robert Rosenfeld

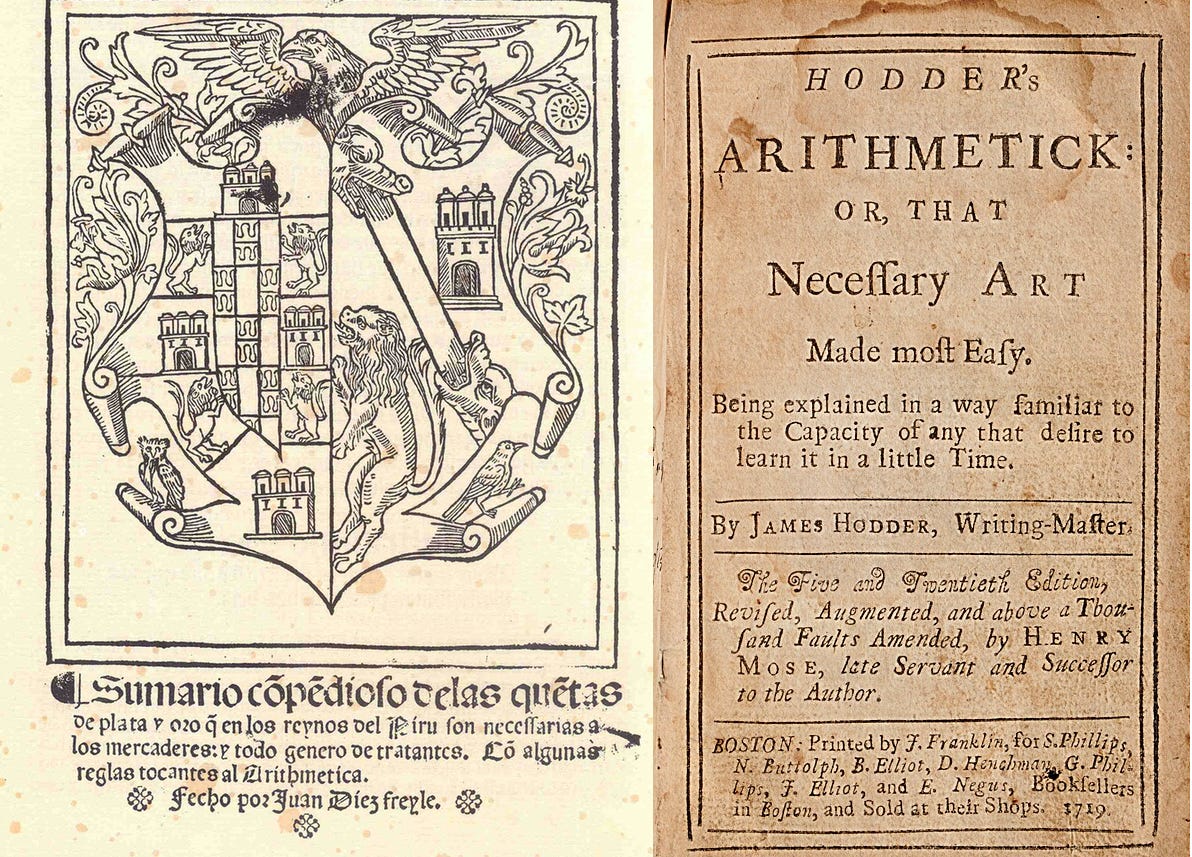

Frontispieces of Summario Compendioso and Hodder’s Arithmetick

The oldest American arithmetic textbook is Sumario Compendioso, printed in Mexico City, the capitol of New Spain, two hundred years before the American War of Independence. It was written in 1556 by Brother Juan Diez Freyle and consisted primarily of rules and tables to help traders of silver and gold, but it also has some straightforward arithmetic and algebra instruction. Brother Juan had first come to the New World in 1518 with the conquistador Hernán Cortés and over the years held various important administrative positions. The printing house was an arm of the Spanish government and church. The first English language arithmetic book did not appear in the New World until 1719, 163 years later. It was James Hodder’s Arithmetick, a Boston copy of a book first published in London. Hodder’s book was influential in America for a long time.

Schooling in the 1600s and early 1700s in the English colonies was quite variable, best organized in the larger towns in the Puritan colonies of New England and least so in the more rural southern colonies. Many children simply had some version of home schooling or instruction from an educated person (often a minister who may have been a college graduate in America or England). A man or woman could set up a “school” at home and tutor several children. Some communities set aside a building as a school. The push for public schools for all children did not take root until well into the nineteenth century. Elementary education often did not include anything about mathematics, only reading and writing. Arithmetic was primarily intended for later use in commercial life and in some specific trades. It could be learned in apprenticeships. If you were among the elite and attended a college, perhaps Harvard or Yale or William and Mary, and wanted to study mathematics, you might use a book from England such as John Ward’s Young Mathematician’s Guide, a monster at some 500 pages, covering material from how to read and write numbers to Newton’s new calculus.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.