Jane Austen’s great and immensely popular novels were published between 1811 and 1817 (she died in 1816 at forty-one of Addison’s disease). George Eliot, coming of age in the 1840s, of course knew them. In fact, in her thirties, when she was living in London and worked as an editor of The Westminster Review, she assigned the writer who would become her future partner a piece which he titled “The Lady Novelists.” The essay, according to Rebecca Mead (author of the wonderful My Life in Middlemarch) covered George Sand, Mrs. Gaskell, Charlotte Brontë, and Jane Austen, whose novels the writer, George Henry Lewes, greatly admired, claiming she was “the greatest artist that has ever written.” He particularly admired a “special quality of womanliness,” which, he suggested, no male pseudonym could have disguised.

As Eliot began to write fiction, she reread Austen’s novels in the evening. “So without Austen, no Eliot,” Rebecca Mead claims, also asking rhetorically, “Could there be a more Austenesque scenario than the beginning of Middlemarch, which presents two young, well-born, unmarried women recently arrived in a country neighborhood, one of them filled with sense and the other brimming with sensibility?”

But influence works in odd ways. Book 1 of Middlemarch, “Miss Brooke,” feels like an Austen novel turned on its side or balanced on a corner.

“He thinks with me,” said Dorothea, to herself, in the strange Chapter Three. The movement of Dorothea’s romance is fast-paced, even for a nineteenth-century novel, and yet it holds—for the reader—no real anticipation of pleasure.

Here is Eliot describing our heroine falling in love: “… the dreams of a girl whose notions about marriage took their color entirely from an exalted enthusiasm about the ends of life (italics mine), an enthusiasm which was lit chiefly by its own fire, and included neither the niceties of the trousseau, the pattern of plate, nor even the honors and sweet joys of the blooming matron.”

“For a long while she had been oppressed by the indefiniteness which hung in her mind, like a thick summer haze, over all her desire to make her life greatly effective. What could she do, what ought she to do?–she, hardly more than a budding woman, but yet with an active conscience and a great mental need, not to be satisfied by a girlish instruction comparable to the nibblings and judgments of a discursive mouse.”

“There would be nothing trivial about our lives. Everyday-things with us would mean the greatest things. It would be like marrying Pascal. I should learn to see the truth by the same light as great men have seen it by. And then I should know what to do, when I got older: I should see how it was possible to lead a grand life here–now–in England. I don’t feel sure about doing good in any way now: everything seems like going on a mission to a people whose language I don’t know;—unless it were building good cottages (!)—there can be no doubt about that. Oh, I hope I should be able to get the people well housed in Lowick! I will draw plenty of plans while I have time” (italics mine).

Eliot notes Dorothea’s “trust” in Casaubon’s “mental wealth,” yet stipulates, in her immense fairness, that “because Miss Brooke was hasty in her trust, it is not therefore clear that Mr. Casaubon was unworthy of it.”

By now, we’ve seen and heard Mr. Casaubon ourselves; we don’t have to rely on Celia’s distaste for his “moles and sallowness.” We can make our own judgements.

Who, so far, feels optimistic about this match?

We’ve learned a bit about Casaubon’s intended work. “With something of the archangelic manner he told her how he had undertaken to show (what indeed had been attempted before, but not with that thoroughness, justice of comparison, and effectiveness of arrangement at which Mr. Casaubon aimed) that all the mythical systems or erratic mythical fragments in the world were corruptions of a tradition originally revealed. Having once mastered the true position and taken a firm footing there, the vast field of mythical constructions became intelligible, nay, luminous with the reflected light of correspondences. But to gather in this great harvest of truth was no light or speedy work.”

This masterwork was to be called The Key to All Mythologies.

One can feel almost as much pity for Mr. Casaubon facing his pigeonholes of “research,” contemplating the task of making a whole out of them, as for Dorothea in imagining their ideal life together.

Even in Dorothea’s inner swoons, a reader might find cause for concern. “This accomplished man condescended to think of a young girl, and take the pains to talk to her, not with absurd compliment, but with an appeal to her understanding, and sometimes with instructive correction. What delightful companionship! Mr. Casaubon seemed even unconscious that trivialities existed, and never handed round that small-talk” (italics mine).

Or: “He talked of what he was interested in, or else he was silent and bowed with sad civility.”

We see Dorothea, walking with Monk, “the Great St. Bernard dog, who always took care of the young ladies in their walks. There had risen before her the girl’s vision of a possible future for herself to which she looked forward with trembling hope, and she wanted to wander on in that visionary future without interruption.”

But interruption she has in the form of Sir James Chettam, who has a Maltese puppy to offer her.

Of course “Miss Brooke was annoyed at the interruption.”

She criticizes the dog and Sir James hands it back to his servant.

“The objectionable puppy, whose nose and eyes were equally black and expressive, was thus got rid of, since Miss Brooke decided that it had better not have been born.”

But then Sir James, with a robust eagerness to please, offers something more appealing than the dog.

“Lovegood was telling me yesterday that you had the best notion in the world of a plan for cottages—quite wonderful for a young lady, he thought. You had a real genus, to use his expression. He said you wanted Mr. Brooke to build a new set of cottages, but he seemed to think it hardly probable that your uncle would consent. Do you know, that is one of the things I wish to do—I mean, on my own estate. I should be so glad to carry out that plan of yours, if you would let me see it. Of course, it is sinking money; that is why people object to it. Laborers can never pay rent to make it answer. But, after all, it is worth doing.”

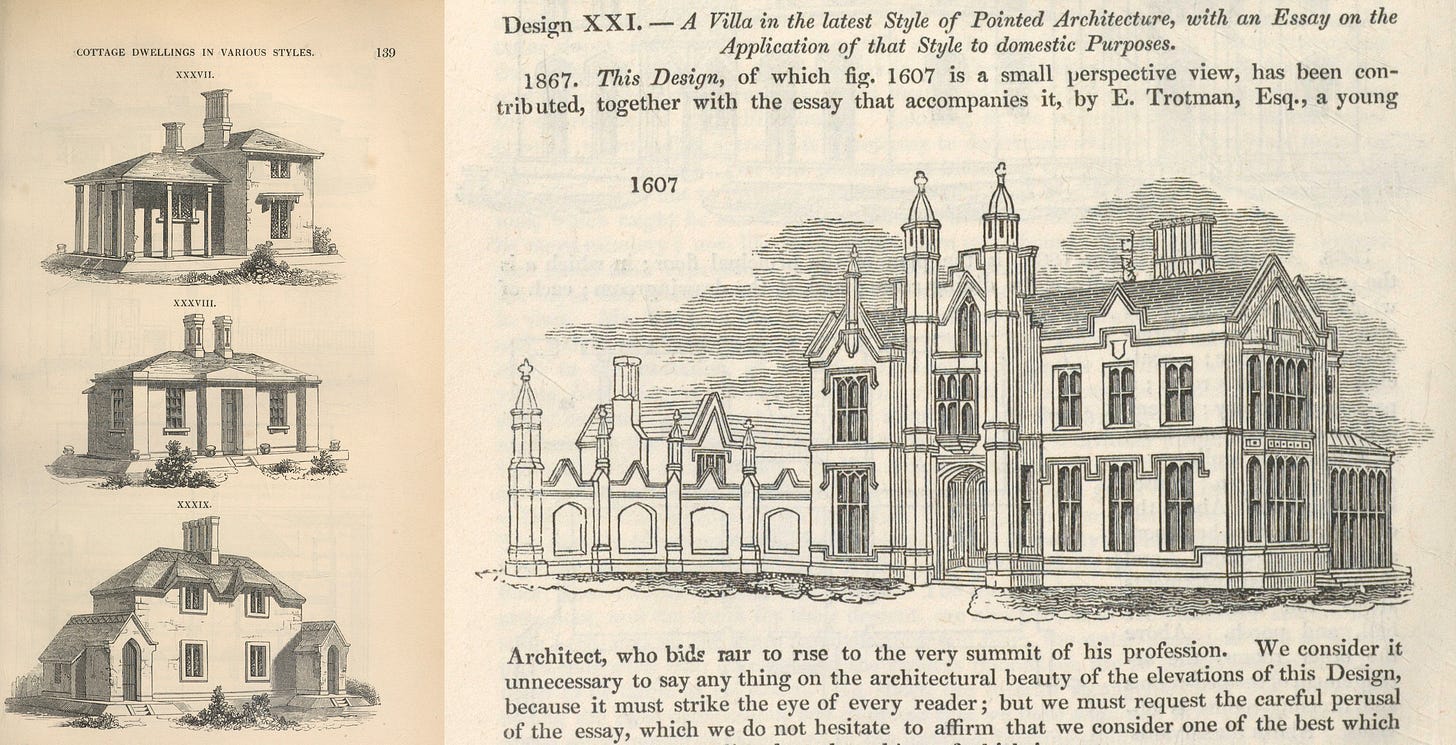

So we are in a Jane Austen plot after all. A spirited beautiful young woman with two suitors: one whose “face was often lit up by a smile like pale wintry sunshine,” who has mentioned “that he felt the disadvantage of loneliness, the need of that cheerful companionship with which the presence of youth can lighten or vary the serious toils of maturity.” The other who engages her in her passion (we know Dorothea has been examining “all the plans for cottages in Loudon’s book”).

But with Eliot we have a character who will not dance to the music. Dorothea’s affections stubbornly stick to Casaubon.

“Sir James, as brother-in-law,” she concedes, “building model cottages on his estate, and then, perhaps, others being built at Lowick, and more and more elsewhere in imitation—it would be as if the spirit of Oberlin had passed over the parishes to make the life of poverty beautiful!”

“On one—only one—of her favorite themes she was disappointed. Mr. Casaubon apparently did not care about building cottages, and diverted the talk to the extremely narrow accommodation which was to be had in the dwellings of the ancient Egyptians, as if to check a too high standard.”

But even this does not put off Dorothea. She assumes “he would not disapprove of her occupying herself with it in leisure moments, as other women expected to occupy themselves with their dress and embroidery.”

Sir James Chettam’s begins the desired improvements on his estate; he and his steward Lovegood calculate estimates and make plans. “He came much oftener than Mr. Casaubon, and Dorothea ceased to find him disagreeable since he showed himself so entirely in earnest.”

Dorothea proposed to build a couple of cottages. Two families were to transfer from their old cabins, “which could then be pulled down, so that new ones could be built on the old sites. Sir James said, ‘Exactly,’ and she bore the word remarkably well.”

Is there any hope for Sir James?

Join us with your thoughts here in the comments! And please share to help our reading group grow. For next Sunday, we’re picking up the pace! Chapters 4 and 5.

Mona Simpson is the author of seven novels, most recently Commitment, which appeared this spring.

To receive Summer Reading installments by email sign up for a free subscription to Book Post. Current Book Post subscribers can opt in or out of Summer Reading in their account settings. Summer Reading subscribers are eligible for bookselling partner Tertulia’s special offer for a 25 percent discount on the pair of Middlemarch and Mona’s new novel, Commitment.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber—or give Book Post as a gift!—to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Coming soon: Joy Williams on Rachel Ingalls, Edward Mendelson on Bible translation, Àlvaro Enrigue on Cristina Maria Garza!

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, Twitter. Special Middlemarch posts on TikTok!

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like.”

Another thought: I noticed that Eliot doesn’t linger much over setting scenes, but she gave us such a luminous picture of the afternoon of Dorothea’s walk, when she was “not consciously seeing, but absorbing into the intensity of her mood, the solemn glory of the afternoon with its long swathes of light between the far-off rows of limes, whose shadows touched each other.” We suddenly feel the breadth of the landscape as an expression of her sense of possibility, such a contrast with the pinched, indoorsy Casaubon. We see her as a romantic heroine in a vista, like a Caspar David Friedrich painting.

“Dorothea by this time had looked deep into the ungauged reservoir of Mr Casaubon’s mind, seeing reflected there in vague labyrinthine extension every quality she herself brought ...” Love how Dorothea is constructing a fantasy about Mr. C. projecting her own qualities and longings onto him.