Let’s try a thought experiment for the narratologists among us.

In Book One and the first part of Book Two, tracks are still visible of Eliot’s decision to merge her two storylines. We know that Eliot wrote the sections about Lydgate, the Vincys, the Garths, Featherstone, and Bulstrode first, then, later, began “Miss Brooke” as another project. Yet she opened Middlemarch with Miss Brooke, introducing her readers to the country estates firsts, the town later.

How would our reading experience be different if we flipped the order, opening with Chapters 11 and 12 about Fred, Rosamond, and Mr. Featherstone? How would we have felt if, instead of ten chapters about Dorothea, Celia, and Mr. Brooke, contending with only two suitors, Sir James and Mr. Casaubon, we had begun with Fred, Rosamond, dying Featherstone, his sister Mrs. Waule, Mary Garth, the Vincy parents, Lydgate, Mr. Bulstrode, and Mr. Farebrother?

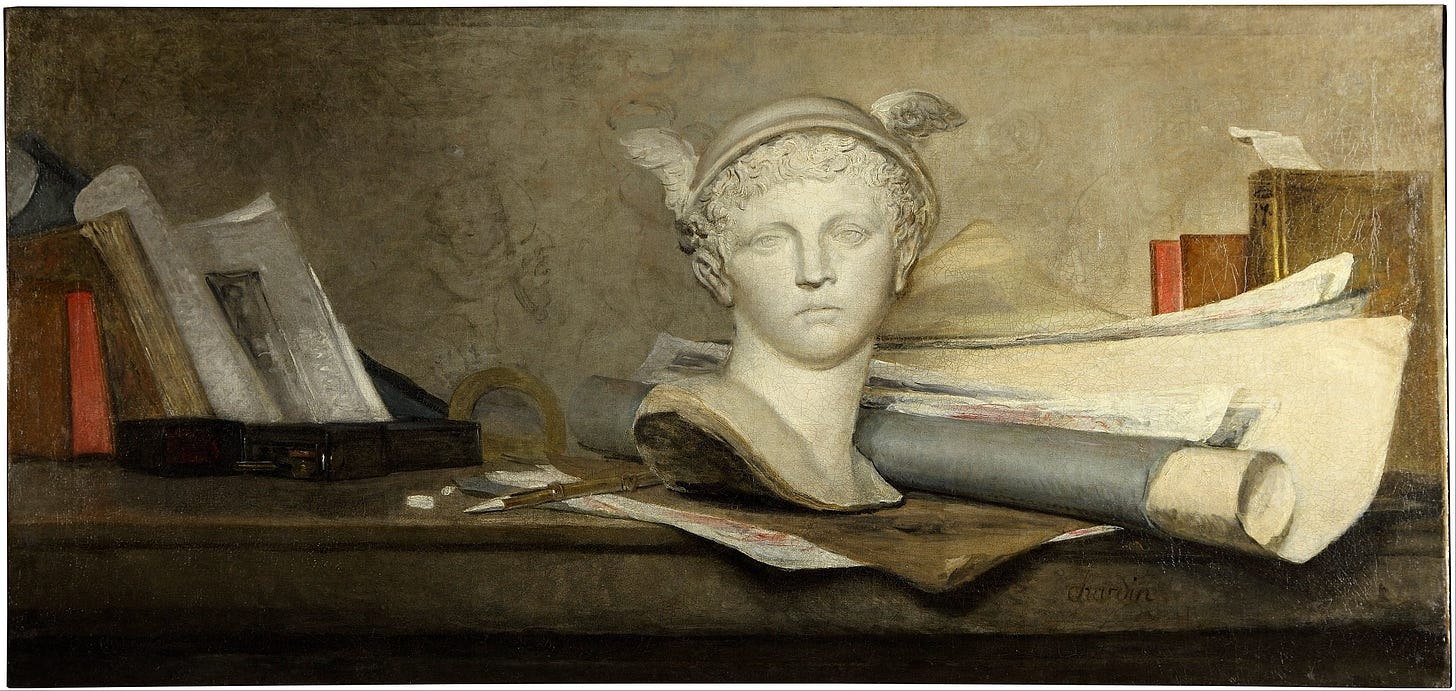

In one central way, Books One and Two mirror each other. In each, we meet an intellectually ambitious young person just beginning an adult life. Dorothea yearns to learn, to do, to be. All the while, she returns to her pastime of drawing cottages, moving a fireplace here or there to offer better floor plans and lives for the peasants on her uncle’s and his neighbor’s estates. Then, once she meets Mr. Casaubon, who seems to her the most promising means to realizing her own ambitions to become learned and spiritually fulfilled, she rushes into engagement, assuming “the really delightful marriage must be that where your husband was a sort of father, and could teach you even Hebrew, if you wished it.” Nonetheless, she intends to take her drawing pencils and plans with her. “I hope I should be able to get the people well housed in Lowick! I will draw plenty of plans while I have time.”

Lydgate has already made a plan for his future: “to do good small work for Middlemarch, and great work for the world.” He will avoid the prestigious cities and make his name in a provincial town with an authentic, sensible practice and also scientific research (he hopes to prove an anatomical conception and make a link in “the chain of discovery”). He pursues this goal deliberately and confidently and, unlike Dorothea, he’s determined that marriage is not on the agenda for him in the next few years.

Indeed, unlike Dorothea, who not long after meeting Mr. Casaubon imagines life with him “would be like marrying Pascal,” Lydgate meets Rosamond several times, finds her enchanting, feels “a hidden soul seemed to be flowing forth from Rosamond’s fingers” when she plays piano at a family party, declares the party “the pleasantest” he has attended since arriving at Middlemarch—but does not plan to return soon. It was a “wretched waste” of an evening he thinks, rushing home to look into “Louis’ new book on Fever,” which he reads “far into the smallest hour.”

In a flashback, we see Lydgate discover his passion for medicine, and this revelation has the quality of large X on the timeline of his life. It’s the beginning of a trajectory that finds Middlemarch on the first third of its arc.

While in Book One we follow Dorothea’s thoughts and feelings as she falls in love with Mr. Casaubon, Eliot does not devote a scene to the discovery of her passion for drawing cottages. We know that Dorothea has read John Claudius Loudon, the landscape gardener and horticultural writer who published Observations on Laying Out Farms, only by a brief reference to him. We never see her reading his book into the night or debating one of his sketches. Drawing cottages seems (even to Dorothea) to be just something she does. Her uncle calls it her “hobby.” Celia refers to the activity as her sister’s “favorite fad.”

Subscribe to Book Post! Bite-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers

In Book Two, Eliot notes that Lydgate brings “a much more testing vision of details and relations into this pathological study [the Fever book] than he had ever thought it necessary to apply to the complexities of love and marriage, these being subjects on which he felt himself amply informed by literature, and that traditional wisdom which is handed down in the genial conversation of men.”

While some of these varied reactions Dorothea and Lydgate have to their intellectual and artistic passions and to love can be attributed to the fact that Dorothea is an heiress and Lydgate a well-born orphan, it seems that the more determining difference is that of gender.

What else do pairings and parallel trajectories allow us to see?

The explanation for Eliot’s decision to open with Miss Brooke could be simplicity. While the first ten chapters of Book One follow the Miss Brookes and their suitors rather exclusively, Chapters 11 and 12, which lead into Book Two, are already a riot of characters and plots.

We have the complicated story of Fred’s debts, his putative inheritance from Mr. Featherstone, his father’s plan for him to become a minister, Mr. Bulstrode’s wish to take the living away from Mr. Farebrother, Rosamond’s flirtation with Lydgate, whom she’s already decided to marry.

And we have many, many more pairings to follow: Rosamond falls in love with Lydgate, envisioning the china and silver of her married life just as Dorothea imagines learning Latin, Greek, and even Hebrew. Each has a sidekick: Dorothea has her sister, Celia, and Rosamond has Mary, whom she’s known all her life. Rosamond and Mary also form a pair in parallel motion, each in love, one beautiful and richer, the other plainer, very intelligent and poorer, one whose primary requirement for a husband is that he be “from somewhere else,” the other in love with the ne’er-do-well boy next door. We have parallel clergymen in Book One and Book Two: the single minister, Farebrother, with his sister, aunt, mother, and a passion for zoology, and Mr. Cadwallader, a married minister with children and a passion for fishing.

Much of Book Two concerns the choice of occupation. Mary and Fred talk to each other about the careers they don’t see themselves fit for. Mary is a caretaker and maid to a cantankerous step-uncle because she didn’t like being a teacher; Fred doesn’t want to be a minister. Only Rosamond accepts her education at face value. Mr. Lydgate, seeing Farebrother’s meticulously collected specimens, wonders whether the church was his profession of choice.

Book Two is about striving, about money and status anxiety. The Vincys, kind and convivial as they are, are portraits of strivers—they’ve educated both their children, according to their genders, in what is supposed to be the most advantageous way to rise up the social ladder.

Book One is almost devoid of money. Money poses no problem, except for farmers in the blurry distance and the minor comic character of Mrs. Cadwallader, who manages well enough by bartering for fowl and training her maid with Mr. Brooke’s pastry chef. While it’s much simpler for us to enter a long complex novel with one heroine center stage for ten chapters in Book One, I think it’s also this fabular quality (lent by the absence of material concerns) that makes for a more enchanting beginning. By the time we reach Book Two, we’re ready for the welter of plots, and the realism of romantic love being put off until an income is secured.

For Sunday, July 23, we are finishing Book Two (through Chapter 22) and then for Sunday, July 30, we are reading all of Book Three (through Chapter 33). We post the schedule also here, under “Summer Reading.”

If you are not yet a Book Post subscriber and would like to receive installments of Summer Reading, sign up for Book Post free posts here. Book Post subscribers can opt in or out of receiving Summer Reading installments in their account settings.

Share your thoughts with us below in the comments!

Mona Simpson is the author of seven novels, most recently Commitment, which appeared this spring.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber—or give Book Post as a gift!—to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Coming soon: Edward Mendelson on Bible translation, Àlvaro Enrigue on Cristina Maria Garza, Joy Williams on Hemingway’s houses.

Rehoboth Beach indie Browseabout Books is Book Post’s Summer 2023 partner bookseller! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com. Read more about Browseabout’s story in here in Book Post.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, Notes, Twitter, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa. Special Middlemarch posts on TikTok!

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like.”

I never thought of myself as a "narratologist" before, but if the shoe fits .. : )

It's interesting to see where Dorothea disappears from the narrative, in Ch. 10 where GE throws a convenient dinner party and deftly shifts to another group of Middlemarchers. I do miss Dorothea and Celia when they disappear - and I mean the two of them together, for Dorothea needs to be "thrown into relief" to borrow a phrase from the beginning! On her own I don't think she can carry the narrative for long. They all need each other for that.

I was thinking along those lines reading the chapters about Lydgate. GE seems almost more interested in him, his past, what makes him tick, his personality, than she does Dorothea. Maybe it's Dorothea's way of thinking that sets the tone for the rest, so the others are all compared to her in some way, when it comes to their assumptions and blindnesses? Lydgate thinks he's not going to make an error after making one before -thinking he'd fallen in love with a woman who actually killed her own husband on purpose - a murderer !.. and still he lives in this kind of self-satisfaction that he knows what he's about .. re-reading that chapter yesterday I saw more of the dark humor in it and the way GE is both building Lydgate up and alerting us to his vulnerabilities to which he himself is comfortably insensible.

I think starting with Dorothea was a good idea because it makes you think you are going to read a love story but you get something different .. if she had started with the Vincy's she would have lost the determining factor of Dorothea's idealism .. it is a very tight little picture in the beginning that sort of naturally widens out to include others who in some way are all variations on Dorothea's pure example.

There's a really interesting section in Michael Gorra's Portrait of a Novel in which he talks about how serial publication affected the structure of the Victorian novel generally and Middlemarch specifically. Worth a read!