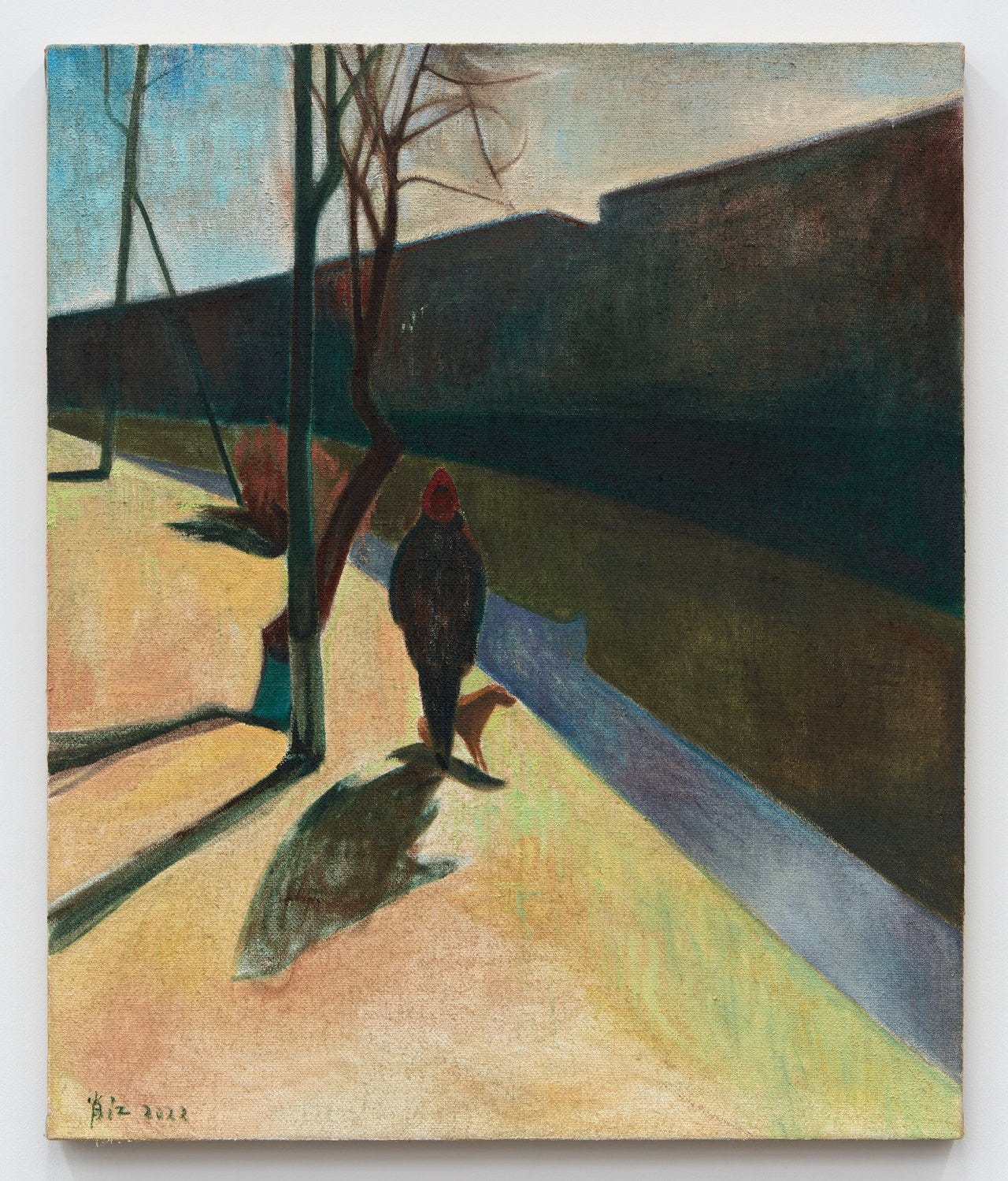

Xiao Jiang, Early Spring in February (2022). Courtesy of Karma

A great reading experience can be like a love affair or a journey—it lives on in memory and in our lives, it touches the way we understand our own decisions, how we fall in love, and the way we approach our work.

Social scientists claim that human beings are biologically prone to overvalue endings; be that as it may, every writer knows that there is nothing more important than her book’s close. Middlemarch offers a gentle, inevitable, and deep ending—one that enters the reader’s own life more than the endings of most books. This is my third time reading the novel and, since finishing, I’ve walked around in a bit of a daze, feeling somehow understood and, even more importantly, forgiven.

In the novel, Eliot poses common questions:

How can we be happy?

How can we do good, for ourselves or others? She also probes and complicates these questions by exposing how little is, after all, within our own power.

From apocryphal, expiring octogenarians to sociologists who study the trajectories of Harvard men over multiple decades, many people will tell us that the most whimsical, romantic, and unreliable of our choices has an outsize impact on our future happiness. That is to say, love, especially as enacted in the form of marriage.

Eliot offers multiple problematic attractions and follows the marriages of three young couples and two older ones.

Only Mary Garth does most everything right (and even she rejects a man who deserves love and, we might note, never finds it), and yet, one could argue that the Mary-Fred union is the most boring in the book. (As Tolstoy pointed out, four years later—Anna Karenina was written between 1875 and 1877—happy families are not nearly so various and compelling as the unhappy ones.)

Our two central characters, our darlings, not only do not marry each other in this novel, but each marries badly. Each picks the wrong person to love. Even so, as Eliot chronicles the history and consequences of their mistakes, she doesn’t give us much hope that either of them could have done otherwise and changed her or his destiny, without the experience they live through with us in the course of the novel.

Eliot takes on the age-old problem that therapists grapple with every day in their practices: love expresses itself by an inner prompting, an intuition, a feeling. Dorothea and Lydgate both have broken romantic compasses. Their deepest intuitions lead them into trouble.

Yet, as even Mr. Brooke knows, in the modern era of 1829, one cannot fall in love by number.

In Book Eight, Eliot’s last installment, we see aftereffects of the mistakes our hero and heroine made epochs ago.

Lydgate and Dorothea respond to their misfortunes in similar ways; as they gradually see who their spouses are, they respond with anger and hurt feelings, sometimes with outbursts, but later they question themselves, take their own share of responsibility, and try to be kind.

Eliot spared Dorothea, and let Casaubon die, but even as a widow she can’t escape the town’s gossip and disapproval because of the codicil in her late husband’s will. We see Lydgate at the nadir of his life, having accepted money from Bulstrode, a man he doesn’t trust and whom he increasingly suspects didn’t follow his orders in taking care of Raffles, who subsequently died. Still, Lydgate is scrupulous. He considers that perhaps Bulstrode didn’t do anything wrong, and he doesn’t want to vindicate himself by throwing his benefactor under the bus.

“Is there a medical man of them all in Middlemarch who would question himself as I do?’ he asks himself.

Lydgate is a pariah in Middlemarch, though his wife doesn’t yet know what’s happened. His reputation and his practice are suffering and may suffer indefinitely. He senses the futility of his position. “Even if I could be cleared by valid evidence, it would make little difference to the blessed world here. I have been set down as tainted and should be cheapened to them all the same.”

While both of her protagonists (not to mention Eliot herself) are hampered and substantially hurt by the cruel judgements of their social worlds, Eliot is rarely funnier than when she describes the gossiping Middlemarchers relishing the troubles of their friends. This is her view of the social world: prompted by “the love of truth—a wide phrase,” our narrator tells us, the neighbors find “a lively objection to seeing a wife look happier than her husband’s character warranted, or manifest too much satisfaction in her lot: the poor thing should have some hint given her that if she knew the truth she would have less complacency in her bonnet, and in light dishes for a supper-party.”

The women in the town move in choral harmony to see that Harriet Bulstrode and Rosamond Lydgate, both still proud and clueless, receive the “moral improvement” offered by the understanding of their new status as social lepers. “On the whole, one might say that an ardent charity was at work setting the virtuous mind to make a neighbor unhappy for her good.” They all notice when Mrs. Bulstrode, despite the scandal, appears at church with her daughters “and they had new Tuscan bonnets.”

“She has always been showy,” says Mrs. Hackbutt, and “all I can say is, that I think she ought to separate from him.”

“I can’t say that,” says Mrs. Sprague. “She took him for better or worse, you know.”

“But ‘worse’ can never mean finding out that your husband is fit for Newgate.”

“Yes, I think myself it is an encouragement to crime if such men are to be taken care of and waited on by good wives,” says Mrs. Tom Toller.

Even here, among the gossips, the question of Book Eight is: what should a person do when they realize they’ve made a terrible mistake? Only Mrs. Plymdale evinces any sympathy. “With all her faults, few women are better” than Harriet Bulstrode. “From a girl she had the neatest ways, and was always good-hearted, and as open as the day. You might look into her drawers when you would—always the same. And so she has brought up Kate and Ellen.”

We watch Mrs. Bulstrode cry in private “from the conviction that her husband was not suffering from bodily illness merely, but from something that afflicted his mind. He would not allow her to read to him, and scarcely to sit with him.” She then goes around town, trying to ascertain what has happened. But the gossips, when confronted by their friend, do not have the nerve to tell her. She finally goes to her best friend, Mrs. Plymdale, but though “beforehand Mrs. Bulstrode had thought that she would sooner question Mrs. Plymdale than any one else” she finds to her surprise “that an old friend is not always the person whom it is easiest to make a confidant of: there was the barrier of remembered communication under other circumstances—there was the dislike of being pitied and informed by one who had been long wont to allow her the superiority.”

Harriet finally goes to her brother and understands from his look that her husband is believed to be guilty.

“People will talk,” he says. “Even if a man has been acquitted by a jury, they’ll talk, and nod and wink—and as far as the world goes, a man might often as well be guilty as not. It’s a breakdown blow, and it damages Lydgate as much as Bulstrode. I don’t pretend to say what is the truth. I only wish we had never heard the name of either Bulstrode or Lydgate. You’d better have been a Vincy all your life, and so had Rosamond … But you must bear up as well as you can, Harriet. People don’t blame you. And I’ll stand by you whatever you make up your mind to do.”

Mrs. Bulstrode locks herself in her room, needing time “to get used to her maimed consciousness, her poor lopped life, before she could walk steadily to the place allotted her … Her honest ostentatious nature made the sharing of a merited dishonor as bitter as it could be to any mortal.” There is never any question of forsaking “the man whose prosperity she had shared through nearly half a life, and who had unvaryingly cherished her.” She knows she will stay with him, she’ll “mourn and not reproach.” But first she sobs out “her farewell to all the gladness and pride of her life.”

As she gets ready to “go down” to join her husband she prepares herself “by some little acts which might seem mere folly to a hard onlooker; they were her way of expressing to all spectators visible or invisible that she had begun a new life in which she embraced humiliation. She took off all her ornaments and put on a plain black gown, and instead of wearing her much-adorned cap and large bows of hair, she brushed her hair down and put on a plain bonnet-cap.”

We can’t help but admire Mrs. Bulstrode’s loyalty. And her kindness is the only thing that manages to make Bulstrode question himself, even a little. His fear of the withdrawal of her love marks the first time he actually feels guilty.

Her mourning dress, her expression, “all said, ‘I know;’ and her hands and eyes rested gently on him. He burst out crying and they cried together, she sitting at his side. They could not yet speak to each other of the shame which she was bearing with him, or of the acts which had brought it down on them. His confession was silent, and her promise of faithfulness was silent.”

For the first time, Bulstrode does not say, “I am innocent.”

Dorothea and Lydgate both stay loyal to their spouses, Dorothea, as we remember, was walking out to give Casaubon her promise of obedience when she finds him dead among the yew trees.

Mr. Vincy is left to tell his daughter, as well as his sister, of her new disgraced position, finally advising, “I think Lydgate must leave the town. Things have gone against him. I dare say he couldn’t help it. I don’t accuse him of any harm.’

Rosamond’s shock is enormous. It doesn’t seem to occur to her, as it does to her aunt, to wonder whether her husband is deserving of the shame his neighbors are inflicting. She’s considering the misery of her own lot, as the wife of a Middlemarch pariah.

The distinction matters greatly to Lydgate, who hopes against hope that his wife will believe in his honesty. “If she has any trust in me—any notion of what I am, she ought to speak now and say that she does not believe I have deserved disgrace.”

“But Rosamond on her side went on moving her fingers languidly.”

Lydgate, we’re told by the narrator, had “almost learned the lesson that he must bend himself to her nature, and that because she came short in her sympathy, he must give the more” (italics mine).

Dorothea, with her husband dead and Will gone, needs someone she can help. The idea of some active good within her reach “haunted her like a passion” when Lydgate comes to talk to her about the funding of the hospital.

“I know the unhappy mistakes about you. I knew them from the first moment to be mistakes. You have never done anything vile. You would not do anything dishonorable.”

It was the first attestment of belief in him since the death of Raffles; “it was something very new and strange in his life that these few words of trust from a woman should be so much to him.”

Even so, he can’t promise to stay in Middlemarch, lead the new hospital which Dorothea offers to fund, because he can’t now “take any step without considering my wife’s happiness. The thing that I might like to do if I were alone, is become impossible to me. I can’t see her miserable. She married me without knowing what she was going into, and it might have been better for her if she had not married me.”

Then there is the last Trollopian plot twist, the repetition of the first scene when Dorothea witnesses what she mistakenly believes is an ardent encounter between Will and Rosamond. Everyone’s pride, you see, must be brought down.

Afterwards, we see Will explode in anger towards Rosamond. “I had one certainty—that she believed in me. Whatever people had said or done about me, she believed in me.” This is Dorothea’s great talent, to believe in the people she loves. It’s an interesting conjecture to wonder whether, after she stops believing in Casaubon’s Key to All Mythologies, she also stops believing in him.

Will’s cruelty to Rosamond is out of character, though it allows one plausible change—after daydreaming about a romance with Will, she’s now able to turn back to her husband.

“If it had been Tertius who stood opposite to her, that look of misery would have been a pang to him, and he would have sunk by her side to comfort her, with that strong-armed comfort which she had often held very cheap.”

Dorothea has a night of sleeping on the floor, “after her lost woman’s pride of reigning in his memory.”

“Oh, I did love him!” she thinks.

Dorothea decides, the next morning, to return to Rosamond to try to prevail upon her to have faith in Lydgate. The two women have an honest vulnerable scene together; “pride was broken down between these two.”

Dorothea talks to Rosamond about straying. “Even if we loved some one else better than—than those we were married to, it would be no use … it murders our marriage—and then the marriage stays with us like a murder—and everything else is gone.” Dorothea assures Rosamond that Lydgate is worthy of respect. “But better days will come. Your husband will be rightly valued. And he depends on you for comfort. He loves you best. The worst loss would be to lose that—and you have not lost it,”

Rosamond then rises to her one moment of generosity in the book. She tells Dorothea that she didn’t witness a love scene, that Will loves only Dorothea.

Finally, appropriately, Will and Dorothea confess their love for each other in a library, where she’s tried to read political economy and study Casaubon’s maps of the world.

“We can never be married,” he says.

“Some time—we might,” says Dorothea, “in a trembling voice.”

“When?” says Will bitterly. “What is the use of counting on any success of mine? It is a mere toss-up whether I shall ever do more than keep myself decently, unless I choose to sell myself as a mere pen and mouthpiece … I could not offer myself to any woman, even if she had no luxuries to renounce.”

“We could live quite well on my own fortune—it is too much—seven hundred a-year—I want so little—no new clothes—and I will learn what everything costs” (italics mine).

This is Eliot’s underlying belief. We won’t be able to direct our desires to the most advantageous objects, we will make mistake after mistake, but we will take responsibility ourselves. Town gossips, never quite believing in the power of the harm they unleash, will always be with us, like the poor. We will learn what everything costs.

Both the Lydgates and Dorothea and Will leave Middlemarch.

“I am going to London,” Dorothea tells Celia, with finality, where Lydgate and Rosamond settle too. We’re left to wonder whether the two friends—Tertius and Dorothea—ever see each other there.

Lydgate’s end cuts deeply, because it is so common. “Lydgate’s hair never became white. He died when he was only fifty, leaving his wife and children provided for by a heavy insurance on his life.” Heartbreaking but characteristic that he had a heavy insurance on his life. He continued to love his wife as best he could.

“He had gained an excellent practice, alternating, according to the season, between London and a Continental bathing-place; having written a treatise on Gout, a disease which has a good deal of wealth on its side. His skill was relied on by many paying patients, but he always regarded himself as a failure: he had not done what he once meant to do … In brief, Lydgate was what is called a successful man.”

While we’re sorry that he had not done what he once meant to do, we can infer some pleasures too, with his daughters and satisfaction at the scientific understanding of a disease, even with wealth on its side. (The contemporary equivalent would be cancer, the disease we invent in most.)

Dorothea’s life feels smaller, too, by the novel’s end, even with a more compatible marriage and two children. “Many who knew her, thought it a pity that so substantive and rare a creature should have been absorbed into the life of another, and be only known in a certain circle as a wife and mother.”

Be only known … as a wife and mother.

In the critical canon, Will is a controversial figure. Many people feel he’s not as memorable a character as Dorothea and Lydgate or even as Farebrother. I find his dialogue sparkling, his scenes with Dorothea palpably charged, yet I don’t remember him when I’m not in the book. His arc is a bit like Fred’s—a slightly indulged, unsettled young man falls in love and shapes up. And Will becomes active in the reform movement. We assume that’s the life into which Dorothea becomes absorbed.

Nonetheless Will feels somewhat irrelevant, except for Dorothea’s happiness. Both Lydgate and Dorothea live on, finally, for other people, not for glory, for their loved ones, whether or not their loved ones are capable of returning that love.

Eliot finishes quietly. “The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.”

It’s a gentle ending that sends us all back to our lives. Lydgate does not become Darwin or Marie Curie; Dorothea does not become Baron Haussmann. They each take care of those closest to them, to whom they make an enormous difference.

It’s ironic that this book, so much about the vanity of seeking to find and publish “the key to all mythologies”—what better parody could there ever be of a masterpiece— should be Eliot’s masterpiece. For the consolation of not being able to write Middlemarch, Eliot gives her heroine the gift of “a noble nature, generous in its wishes, ardent in its charity,” which “changes the lights for us: we begin to see things again in their larger, quieter masses, and to believe that we too can be seen and judged in the wholeness of our character.”

We too, can make life a little better for some other people before we rest in unvisited tombs.

Mona Simpson is the author of seven novels, most recently Commitment, which appeared this spring.

We have so enjoyed reading Middlemarch with you; we thank you so much for being a part of Summer Reading! We are putting together some follow-on conversations this fall and we will let you know how these go. We look forward to seeing you in our future Book Post endeavors and finding you in our closing conversation, below.

I'm sorry our summer of Middlemarch is ending. It's been wonderful. It does feel right, somehow, that Dorothea and Lydgate both leave Middlemarch, both because of their spouses.

Thank you so much. How was Idalia? (I've lost track of Hurricane names. I had to make an earlier-than-expected departure from Mississippi to get home before LA's hurricane -- was it Hilary?)

Thank you so much for this nuanced note. I love the idea of analyzing the first and second marriages here...I'll ask Aaron Matz if he will share his paper.

ps -- I agree! Let's throw out all the rules