Notebook: (1) Some Men Reading

Reading in a way that makes people feel like they are a part of something

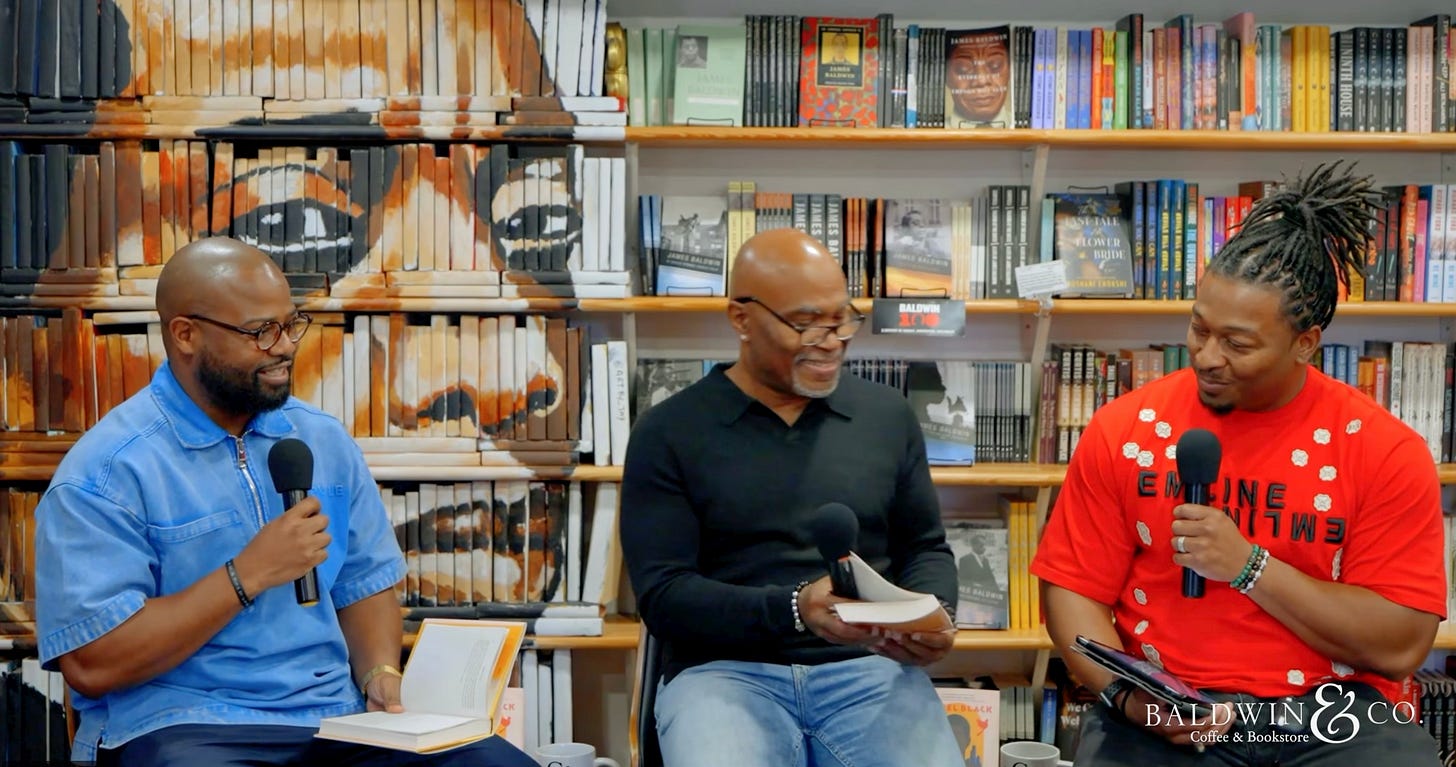

Pastor Jonathan Everett, novelist Daniel Black, and Dr. Jerid P. Woods at Baldwin & Co. Bookstore in December

Let me explain something, because I just figured this out about myself. People say that a bibliophile is someone who loves books. Cool, respectable, very dictionary.

But what do you call someone who doesn’t just love books, but someone whose walk looks like it was edited by a library? Yeah, that’s different. That’s what I like to call bibliolific living.

You see, I used to collect books, heavy emphasis on used to. Now, I live with them. I work with them.

These aren’t books that just sit on shelves looking cute and unopened. These are books that share oxygen with me. Books that know my moods, books that whisper, Yo, you good? Sit down. We got you. Some people call this a clutter, but me, I call community, because look at my life, I’ve got books everywhere…

You see, at some point, I realized these books aren’t decorated in my space, they’re making me comfortable inside myself. Some folks collect sneakers, some folks collect wine, I collect both, but I also collect sentences that rearrange my spirit. So if a bibliophile loves books then the bibliolific life is when the books love you back.

Yeah, that’s right.

This is Jerid P. Woods, speaking on his Instagram feed, @ablackmanreading.

He was born and raised in Natchez, Mississippi, and became a high school teacher in Hattiesburg after a somewhat indifferent stint at the University of Southern Mississippi. In 2018 he started posting online as @ablackmanreading. In one of his early posts, under his sometime nom de plume Akili Nzuri, he explained that he had been drawn to a line from Will Smith who said that “finding one’s purpose was grounded in exploring and experiencing.” “It has been my experience,” he went on, “that exploration has led me to many things, especially books, which have provided me with multiple means of adding others’ experiences to my own … Books have always been a symbol of humanity’s on-going search for themselves as well as a symbol of man’s search for his place relative to the world. Here I will seek to explore and experience through not only books, but music, cigars, politics, and whatever catches my eyes and ears.” In his early posts this project of self-discovery is interwoven with his motivation to help his young students find their way in the world. He cites the same quote from James Baldwin that is a motto of sorts for our current partner bookstore, Baldwin & Co. in New Orleans. “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

Flash forward to 2026. Jerid Woods has just received a doctorate from the University of Southern Mississippi and he is the Customer Relations and Partnership Manager at Baldwin & Co., still running @ablackmanreading while also hosting podcasts with famous writers as part of the store’s “Baldwin Dialogues” (organized in the spirit of founder DJ Johnson’s aspiration to revive the nineteenth-century tradition of the lyceum) and a book club (“bring your thoughts, your stories, your people; because we’re reading, we’re building, we’re growing together”) and the very interesting job of facilitating institutional bookstore partnerships. His almost uncountable output of podcasts, videos, social media posts, and collaborations to this day brims with joy and intellectual enthusiasm. He began a recent podcast series saying he was doing it “because books still matter. Not just posting about them, but reading them, living with them, and letting them shift us … it’s important to think deeply and critically about all of it. The books, the music, the headlines, the shows, because that’s how we grow our own understanding, instead of just inheriting someone else’s.”

Last summer I heard Baldwin & Co. founder DJ Johnson talk about a program the store had to invite local kids, many of them underprivileged, who came to their story time to earn a little sum to read books and review them for the store’s web site, sums that could be deposited in a college fund in the store’s adjoining credit union, contributing to advancing their education without debt and thereby potentially lifting a whole family’s financial trajectory, in addition to encouraging them to read (see our November profile of Baldwin & Co.); he also described how the store uses its podcast studio both as an invitation for neighbors to come off the street and to spread the word, by excerpting passages from videos and podcasts of the store’s author appearances and spreading them algorithmically on Instagram and TikTok and YouTube, becoming visible to people who may not realize they are interested in books.

At the moment I heard about these ideas from DJ the literary internet was awash in commentary about “men reading,” how they weren’t doing enough of it, whose fault that was, and what the consequences might be. Here were original, practical, positive ideas about how to capture the attention of people who might not think they want to read. I thought, I’ll partner with Baldwin & Co. this fall and try to learn more.

Jerid Woods’s project is all about surmounting the barriers that make people think reading is not for them, especially men. As, just last week, advocate and author Shaka Senghor said in a Baldwin Dialogue with Jerid Woods, “We have to make intellectualism cool again,” noting that in “the Harlem Renaissance the writers were the keepers of the culture.” In a solo episode of “Lost in the Woods” Jerid Woods sets fictional characters up like competing rappers, challenging each other with their worldviews. Indeed music and literature often emerge in his conversations as serving the community spiritually in similar ways. In a podcast with theologian and author Danté Stewart they discuss music’s role in Black spiritual formation, and how music that connects with your soul creates “an intimacy, a closeness that happens between art and your heart” that becomes “a reservoir of grace and hope that you can like lean on.” “Much of hip hop,” Danté Stewart says, “is also about paying attention and being aware, attuning to things that people are missing,” and “this quest to be the best version of ourselves is spirituality. It’s to pay attention.”

fIn another podcast with music critic and essayist Lawrence Burney, Jerid Woods says “I think books and music are carrying on, like, the divinity that our grandmothers wanted to hand us through church,” and author Kiese Laymon says, in the extraordinary first interview of “Lost in the Woods,” that he is “trying to make the sentence do a little bit of what I saw my auntie do with gospel and soul, and then what I saw MCs do with the actual sentence, not just with the rhyme, but with the sentence. Because even now, when I think of a rhyme, like I still see it in sentence form, you know what I’m saying? I’m like, I break the paragraph there, I put a comma there, even though these dudes are thinking writing in verse or writing in line, and it’s a completely different scenario.”

The conversations often also address arriving at a new ideas of masculinity, envisioning the reading man as someone who listens and seeks to grow and is not driven to dominate. Jerid Woods often cites bell hooks on love: “It is the most militant, most radical intervention anyone can make to not only speak of love, but to engage in the practice of love. For love as the foundation of all social movements for self-determination is the only way we create a world that domination and dominator thinking cannot destroy. Anytime we do the work of love we are doing the work of ending domination,” while “the world keeps trying to convince us that to care is weak, that softness will get you crushed.” In his solo episode about the two fictional characters, Milkman Dead from Song of Solomon and King Tremain from Guy Johnson’s Standing at the Scratch Line, Jerid Woods speaks of a moment in which “a man stops fighting to be powerful and starts learning to be present,” and that somewhere between the two characters, one who is a “drifter” and one who is a “builder,” “lies the map to a spiritual adulthood that I want to offer us.” In the podcast with Danté Stewart they discuss hip hop as speaking to “men wrestling with absent fathers,” “teaching Black men how to be men,” and that passing on music to sons is a way for Black men to communicate values intergenerationally. In another recent Baldwin & Co. conversation, novelist Daniel Black says, “this is the generational healing that needs to happen badly,” generational healing that is facilitated by music and reading that can carry spiritual lessons from one generation to another when family ties have been broken. (Later in the interview he offers that Black men “left [the plantation] with the hopes that the white man’s manhood would one day be ours because that looked like power,” when “the dream should really be the destruction of the master-slave narrative period, not the dream of my turn”). Jerid Woods says that when he first started @ablackmanreading people kept assuming it was some kind of assignment, but “reading doesn’t have to be forced on me, it’s my birthright.” He labors to undo a sense that reading has to be something punishing and joyless that makes you feel bad about yourself.

Listening to Jerid Woods’s videos reminded me of another person who has done enormously original work to bring men to reading, Simon & Schuster senior editor Yahdon Israel. Yahdon Israel first made his mark as a young essayist with an at-first-casual post, also on Instagram, of someone looking good while reading on the subway, attaching the hashtag #literaryswag. He started noticing and photographing other well-dressed people with books and the hashtag became an Instagram feed which came to host conversations and meetings with authors and evolved into an in-real-life book club meeting in a clothing store in Gowanus, Brooklyn (after starting out at The Strand).

Yahdon Israel has said of yoking fashion to books that, like Jerid Woods, he wants to make literature cool, like movies and music; to separate it from the social signifiers (a haughty disdain for “materialism”) that mark it as the property of a certain demographic. “The intellectual crowd usually didn’t dress in a way that made me interested in or inspired by what they did,” he said in an interview. He used fashion as a teenager in Bed Stuy to protect him from the stigma of being a student and a reader; attaching fashion to reading he saw as a way of opening its availability to people who lacked a way into the literary world. “I remember going into these literary spaces, and feeling cold, cold to the touch,” he told the critic Merve Emre in a wide-ranging interview in The New York Review of Books. “I internalized this fear of not looking literary.” On the other hand, “when you look at The Dick Cavett Show, you had Truman Capote or James Baldwin sitting next to Lena Horne.” But these days among intellectuals there seemed to be “this understanding that … if you wanted to be materialistic, you could not have a conscience … If art is cool, it cannot be of substance … When I say swagger, I mean influence with integrity. What I mean by influence with integrity is conviction.” #Literaryswag came out of “a deeper desire to encourage more people to [read and write] without feeling like they have to give something up.”

His own good taste, playful and colorful, “becomes identified with literature, insofar as you trust my taste to the point that I can help make books, reading and literary culture popular.” Another commonality is recasting acquisitiveness as an exuberance around owning physical books: Jerid Woods celebrates his book collection, and Yahdon Israel, in an essay called “Why Hardcover Is the New Vinyl,” eschews screens and says “I want to feel as connected as I possibly can to the world around me. Having all that weight, the weight of so many books, reminds me of this … I was conscious of that hardcover [a first edition of a book by Margo Jefferson] from the moment I touched it. I was aware of its weight, its burden, and the responsibility it demanded of me.”

The Literary Swag book club gatherings were designed to “make people feel like they can walk in and immediately become a part of something,” he has said. “As we are a community committed to bridging the gap between people who love books and people who have never had a chance, it was important for us to eliminate the barriers of entry that have traditionally kept people out. Engaging in the conversation, and connecting with community is our priority,” he said on Instagram. He was looking in his gatherings for “a barber shop mentality.”

A few years ago he was speaking with then Simon & Schuster Vice President and Publisher Dana Canedy and told her, that he “wanted to be a part of bookmaking, but I thought the only way that I could do that was by writing books.” She told him that it broke her heart that he didn’t know he could be an editor. “She was like, ‘you’ve been doing editorial, curating and finding an audience and all these different things. You’ve been galvanizing books, and talking to writers, you’ve been doing the work of an editor and you didn’t know that.” She led the way to getting him hired as an editor at Simon & Schuster, where he has done revolutionary things to open up the process and work with new writers to make them “more effective vehicles for the transmission of their message” in a punishing commercial environment, learning “how to develop a career to the point where you can have a real impact on the culture.” He received his first acquisition, Temple Folk, from Aaliyah Bilal when she was an unagented, self-taught writer who responded to an email address he posted on Instagram. It became a National Book Award finalist (and was reviewed for us by Allan Callahan). He created an Advance Readers Club that would give regular people access to early copies of books. (Simon & Schuster made another effort to drum up the elusive male reader by hiring glossy magazine editor Sean Manning.)

Yahdon Israel’s work as a journalist and a curator has also addressed the tensions between masculinity and reading. Last fall he started “The Fiction Revival,” a book club for heterosexual men built around his reflections on an observation from Ursula LeGuin’s essay “Why Are Americans Afraid of Dragons?”: “Men are not taught to embrace their imaginations,” he took from the essay, “lest they be dismissed as ‘womanish’ or ‘childish.’ They are hardly taught to read for pleasure, she believes, but often taught to read for productivity.” In an Instagram live announcing the book club he characterized it as a “case for the imagination,” for “free play of the mind,” that is “done without an immediate object or profit,” but that “does not mean there is not a purpose.” (The value of work without immediate tangible reward also comes up in Jerid Woods’s conversation with Kiese Laymon, when he described Kiese Laymon’s auntie’s masterful church singing, “without any hope of material gain,” as a model for art. “To strive for mastery without any proof of material benefit is how you express your love for people, for a city, or a neighborhood, for a block.”)

In Yahdon Israel’s writings and Jerid Woods’s conversations you find reference to a matrilinear inheritance of reading: mothers teaching sons to read, mothers pressing them to go to school, women writers—and also gay writers—opening them up to more expansive ways of experiencing masculinity. Yahdon Israel writes of his mother communicating a painful expectation that he think critically—“read” the world. They share a sense of gratitude toward women for literary experience and a desire to model a vision of success in ways that include women as well as LGBTQ people. “You cannot seek liberation while denying it to those walking beside you…”

Read Part Two of this post here

Ann Kjellberg is the founding editor of Book Post. Read her Notebooks on books and the reading life here (Reader’s Guide here).

Read about our other two Black-owned partner bookstores, Source Booksellers in Detroit (and its founder Janet Webster Jones) and Black Stone Bookstore and Cultural Center in Ypsilante.

Baldwin & Co, in New Orleans, is Book Post’s Winter 2025–26 bookselling partner! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com. And support the Baldwin & Co nonprofit’s mission of leveraging the power of books to ignite social justice and inspire change with your donation or membership—or see if there are ways to support your local bookseller financially.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa