Notebook: Boxed Out (Part Two)

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

(Read Part One of this post here)

As independent bookstores struggle for survival facing a perilous fall season, publishers are in a somewhat tricky spot. Threatened themselves by the prospect of declines in consumer spending, they have a commercial incentive to cut out the ailing middleman and market directly to consumers. In September the New York Times reported that Penguin Random House, the giant that has gobbled up many of the publishers you have heard of, has taken a page from Amazon’s book and “built what is probably the most sophisticated direct-to-consumer online marketing and data operation in the industry, with a proprietary research operation that tracks 100,000 book buyers across the country.” Analysts quoted in the story argued that such mechanisms are freezing out medium-sized publishers and diversity in what gets published: “As publishing becomes even more of a winner-take-all business,” it has, like Hollywood, “become increasingly reliant on blockbusters.” Said Michael Cader, the founder of Publishers Marketplace, “They’re not going to have the next wave of books sitting in the backlist if they take away the lesson that they don’t need anything other than the big books.” Publishers also have an incentive, as noted in last month’s House antitrust report, to direct marketing dollars toward Amazon in order to secure favorable search placement.

Josh Cook, the co-owner of the Publishers Weekly’s Bookstore of the Year, Porter Square Books, noted in a Twitter thread way back in February that independent bookstores do not suffer as much as the industry generally when there are not blockbusters on tap because “contemporary indie bookstores are really fucking good at selling books. You come in for 1 book, you leave with 3. You come just to browse, you leave with 3.” Indie bookselling, in short, may not always serve the immediate bottom line as much as a mega-bestseller, but it is vital to the reading ecosystem: not only supporting a range of writers and publishers (and ideas) but selling the books that are cultivating the careers and the readers that publishing will need for the fertile backlists of the future.

What are publishers doing for these vital partners in this life-and-death moment? Well, at the end of October PRH announced a “Books Give More” campaign that puts some promotional muscle behind a selection of their books and gives indie bookstores a “marketing credit” for selling them, as well as a virtual events support program. Workman announced a "Shop Local NOW, So You Can Shop Local FOREVER” campaign, with videos of authors and a cute poster by illustrator Jon Klassen (“a spot of light a good book and off I go”). Visitors to the Frankfurt Book Fair learned that German publisher Kiepenheuer & Witsch staged a four-hour online recitation, broadcast on YouTube, of German-language authors reciting the names of four thousand independent bookstores in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Perhaps more substantively, Brazilian publisher Companhia das Letras is offering bookstores loans. Cook’s idea was more ambitious: create a grant-making nonprofit or B-corporation to support independent booksellers and the creation of bookstores in underserved communities.

Book Post supports books & readers, writers & ideas

across a fractured media landscape

Subscribe to be a part of our work

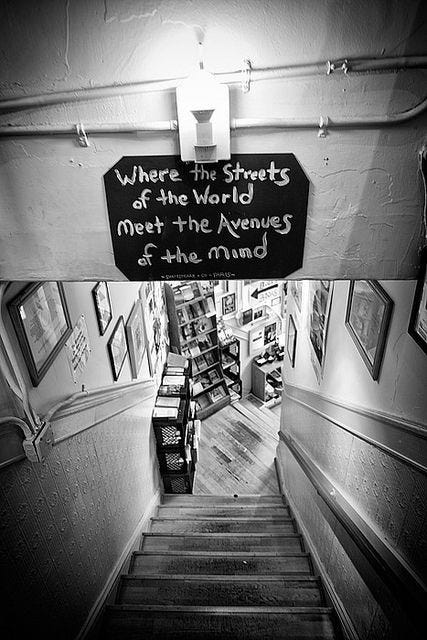

Meanwhile, a few miles from Silicon Valley, a fabled anniversary reminded readers of the San Francisco of yore—the sort of place that drew to it the erstwhile big-thinkers and rule-breakers who would bring us tech as we know it. Veteran San Francisco book-buyer Paul Yamazaki celebrated his fiftieth year in bookselling, at City Lights Bookstore, the fabled beat destination described by Point Reyes Books’ Stephen Sparks as “possibly the most thoughtfully curated bookstore in the world.” Yamazaki recalled in a conversation with Sparks a few weeks ago in the California literary magazine Zyzzyva how the poet and City Lights founder Lawrence Ferlinghetti had given him his first job to help him get out of jail: “Lawrence was sympathetic to someone he considered a political prisoner.”

Yamazaki recalled the importance of neighborhood to City Light’s signature bohemian spirit: “the number of poets and painters sharing flats, being neighbors, living in close proximity, helped City Lights become the place it is.” (Added Sparks: “Having a bar near a bookstore that’s conducive to conversation and bartenders who don’t mind you nursing a beer while you read for a few hours is of great importance to the development of my professional skill set.”) That the real estate crisis in San Francisco—another consequence of big tech—now constrains not only the ability of visionary small businesses to open, but also for a supportive community to embrace them, looms in the background of of a story featuring walk-ons by the likes of Patti Smith and Allen Ginsberg. (Our current indie partner Malaprop’s former manager Linda-Marie Barrett said of the neighborhood they helped put on the map: “It’s a challenge as a bookseller to live in a town where housing is so expensive.”)

Sparks praises Yamazaki’s “panoptic vision” as a buyer; Yamazaki advocated for the store to depart from its original paperback-only mission in order to participate in the arrival of new work: “My contention at the time was to ask if it was more important to have a format or a mission? We weren’t shaping literary taste.” Says Yamazaki, “Some of what we know is really good will not be in the short term economically viable. I’m in a privileged position at City Lights to be able to order those books I think will last or whose cultural impact won’t come for years. When we look at the great booksellers through the US, most of us agree that there are certain books and certain authors we fight for … Almost every book needs time.” He talks about how they stocked and recommended Cormac McCarthy for years before McCarthy broke through with All the Pretty Horses. “I think we were the only store to sell Blood Meridian as an original hardcover in double digits. It was only like fifteen copies!” (Sparks wonders if other bookstores could be so patient if they too owned their buildings.) Yamazaki notes also that “One of the reasons for City Lights’s success is due to the fact that many of our employees, about half of whom are people of color, recognized themselves in books on the shelves. There’s a correlation there.” He asks if regional associations could help support booksellers to be deliberate about giving books by writers of color time to grow on bookstore shelves.

But really don’t listen to me, read this whole wonderful interview for its immersion in the confluence of literature, personality, and place that makes for great bookselling and vital intellectual culture. Reflects Yamazaki in another recent conversation, “Over the first decade here I worked the night shifts. I closed the store for many many years. Still my favorite time to be in the store is after we close. Go out for a drink, maybe come back. 3:00 [am] is the magic time here, because the streets have gone quiet, the bars have let out. So there’s a stillness, out on the streets, there’s a stillness in the store. To sit quietly in the store at that moment is still one of my favorite things.”

More on Paul Yamazaki (bio)

January 2013 Interview with Siglio publishers

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti has always thought of City Lights as being part of a long tradition of resistance and dissent, a beacon of possibility and a place of refuge to consider the long horizon of potential futures. He has always felt it was imperative that City Lights be a place of lively stillness, where the browser/reader could peruse the shelves, select several books and read them at one’s own pace.”

January 2017 Appearance at the De Menil Collection in Houston, TX, as part of the exhibition Holy Barbarians: Beat Culture on the West Coat

“Fifteen- to thirty-five-year-olds have so much discernment in terms of what platforms they chose to read on. Younger readers have a very profound understanding of what works for them on a screen and what works for them in print. For most poetry, for most long-form narrative nonfiction, for most fiction, they prefer print. The last seven years at City Lights have been the best seven years in terms of gross sales. And it’s not just City Lights. We’re seeing a whole new generation of readers, writers, people coming into publishing. We still have issues about race and class that we haven’t dealt with that are very difficult and need to be discussed, but … in all the years I’ve been doing this, this is one of the most exciting times, because of the quality of work that’s getting published, who’s writing, who’s reading, who’s selling books.”

April 2020 TV interview about City Lights’ response to the pandemic

“One of the things that keeps City Lights afloat is our staff, and we have maintained our staff through this whole period, and that’s what our goal is … Our whole staff is involved in the books we select, so we have this incredibly deep and diverse collection of books that many generations of booksellers have contributed to.”

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box, as well as free posts from time to time like this one. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Recent reviews: Rebecca Chace on N. K. Jemisin in dark times, Alex Ross on John Luther Adams in the wilderness

Malaprop’s Bookstore/Cafe, in Asheville, North Carolina, is Book Post’s Autumn 2020 partner bookstore! We support independent bookselling by linking to independent bookstores and bringing you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 there during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”