Notebook: On the Road with Bookmobiles, Part II

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

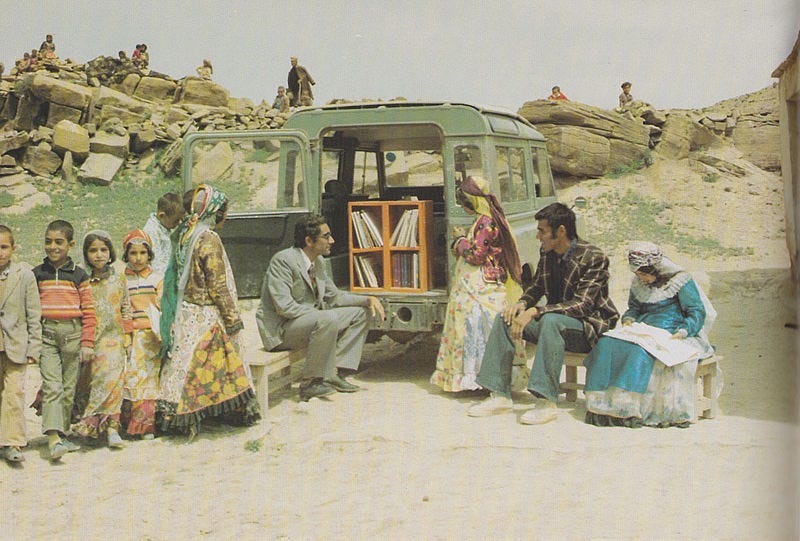

Mobile book van in Iran, 1970. From Eduscapes: History of Libraries

Read Part One of this post here!

Mobile libraries are used around the world to access remote populations. India launched its first bookmobile in 1931; Tasmania in 1941; bookmobiles were popular in South Africa in the fifties and sixties. Iran had mobile libraries in 1,200 villages by 1975. Thailand has a long history, that continues to this day, of supplying books by elephant, and by boat in Bangkok. Llamas transport libraries in the Andes, and mules in Columbia, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe. A Camel Library Service was launched by the Kenyan government in 1996. The Kuda Pustaka (“horse library”) of Ridwan Sururi delivers books in an area of Java with high rates of illiteracy on Sururi’s horse Luna. Teacher Luis Soriano and his two donkeys, “Biblioburros” Alfa and Beto, bring books to children in rural Colombian villages. (See more mobile libraries around the world here.)

Although library bookmobiles now number less than a thousand, from a midcentury peak of two thousand, they are still actively supported by the ALA as a way to reach isolated readers—both in rural areas and, for example, in senior homes. Each April the ALA sponsors a Bookmobile Day, and the organization provides detailed instructions on its website on the care and maintenance of one’s bookmobile. An Association of Bookmobile and Outreach Services supports bookmobiles with an annual conference and a newsletter (this month: circulating Mac the robo cat to Alzheimer’s patients in Detroit). Remote and rural libraries remain a cherished resource in the library system. In an article in this month’s School Library Journal, Wayne d’Orio writes

In Trinidad, Colorado, one librarian spends most of her time securing food and services for her town’s homeless population. In Show Low, Arizona, another librarian runs “adulting” classes to teach teenagers “the skills they don’t get in high school anymore.” And in Stanley, Idaho, the library’s Wi-Fi is such a draw that the librarian installed a router outside and added benches and power outlets so people can get online even when the library is closed. In many of these communities, “the library is the living room of the town,” says Clancy Pool, the branch manager of the St. John (Washington) Library.

The article reports that more than 6,000 of the country’s 17,000 individual libraries serve areas with populations of fewer than 2,500. They average roughly 2,600 square feet, slightly larger than the typical American house, and 1.9 full-time staff members. About 60 percent are not connected to a broader library system. Says Chelsea Price of her Meservey, Iowa, library (population 48), the nearest movie theater is about thirty miles away, the closest school is twenty miles outside town, here “there’s nothing else. There’s no community center, no bank, no gas station. There’s just a post office, a church, a bar, and the library.”

The Pew Charitable Trust reports that Kentucky has still seventy-five bookmobiles, the most of any state. Some of these conditions seem not too far from what drove librarians on horseback into Appalachia in the thirties and sorority sisters into segregated North Carolina in the fifties. A Pew study shows that about 32 percent of rural Americans said they hadn’t read a book in the past year, and nearly 1 in 5 people who live in non-metro areas live more than six miles from a public library.

It’s interesting to think about what the mobile library/bookstore idea has to offer in the age of the internet. In one sense technology has arisen to fill the immediate need that the nineteenth-century bookmobiles responded to: disseminating knowledge among those who were too poor and isolated to be within reach of cultural institutions. But what we see in the vitality of physical libraries and bookstores and their mobile outposts is the still-urgent need for hubs of live human interaction—at the heart of what we now call “curatorship”—to delimit and advocate and personalize within world’s vast troves of information. Plus—the reach of the internet, and the wherewithal to make constructive use of it, are still far from universal.

The convenience of obtaining information has perhaps drained some of the urgency and effort from the pioneers who carried books to lighthouses and farms and ranches and work camps and neighborhoods marginalized by Jim Crow. But plainly such places still welcome the arrival of a person bearing a book. Maybe the spread of learning doesn’t happen by itself and we need to pick up again some of the old human energy behind it. SLJ reports that in 2007 97 percent of rural librarians expressed satisfaction in their jobs. Said Lisa Lewis, president of the Association for Rural & Small Libraries, of working in her library: “There’s no place I’d rather be. We can make a whole lot of difference. You’re not just another library card member—we know who you are and we’re concerned about you.”

Read Part I of this post here

Book Post is a by-subscription book-review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to subscribers’ in-boxes, and other tasty items celebrating book life, like this one, to those who have signed up for our free posts and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend! Recent reviews include Adam Hochschild on unsung heroes of the Nazi Resistance and Madison Smartt Bell on Rumer Godden. Coming up we have Sarah Kerr on Carlos Bulosan and Jeff Madrick on the future of work.

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s spring partner bookstore is The Raven in Lawrence, Kansas. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

I'm enjoying your bookmobile series, Ann. The bookmobile has been part of Franklin County, Virginia's library system for as long as I can remember. There was a time when it stopped in an elderly cousin's driveway in our little town because she was no longer able to get to the library. Until a few years ago, there was only one public library for the entire county of almost 720 square miles and 55,000+ people. There are now two libraries, but the bookmobile is still actively getting books, information and mobile programs to people in isolated areas. Our county also has four Little Free Libraries that get a lot of attention. https://littlefreelibrary.org/