Notebook: Unevenly Distributed

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

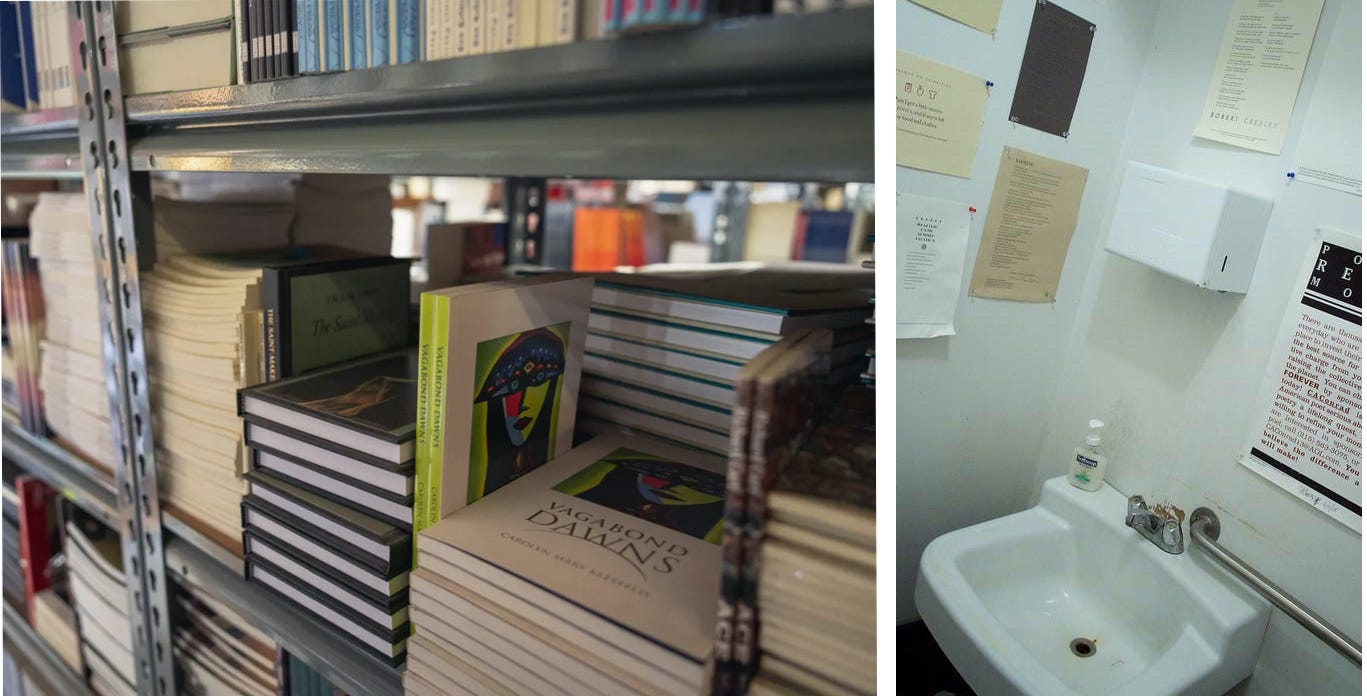

Inside Small Press Distribution in Berkeley, California. Readers could show up at that door and pick up a book.

Perhaps book distribution does not sound like the most exciting subject to you. I myself can claim no expertise! When I try to follow booksellers chatting on this topic I feel like I’m in Cape Canaveral. But plunging in this week (for reasons I will get to) I found the history notably colorful—indeed, pivotal! To go by Buz and Janet Teacher’s recent omnibus of publishing lore, Among Friends, most of the early US book distributors seem to have gotten their start in Berkeley, where, after a day of pouring over piles of three-by-five index cards tracking inventory, they would head for the warehouse, turn up the music, get high, and start packing books. They rival each other in descriptions of how laid back they were. Many, like their counterparts in the almost accidental alternative California publishing scene that brought us The Whole Earth Catalog, Juggling for the Complete Klutz, and The Moosewood Cookbook, stumbled into it after a few post-college years building geodesic domes, picking lemons, or river rafting. But they knew they had information to share and an audience for it that were not being covered by the notably clubby circles making publishing decisions Back East. They were also far away from a lot of the books: another early distributor, Raymar, was created because the postal service book rate (for which this newsletter is named!) was so slow, and shipping heavy books so expensive, that West Coast booksellers needed someone just to get the books physically across the country to them before they were out of date.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.