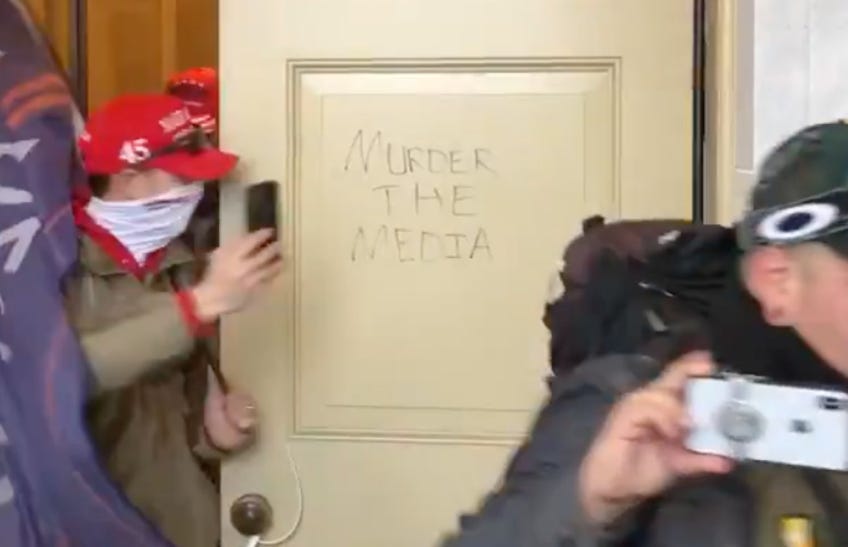

Notebook: Writing in the Crosshairs

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

United States Capital, January 6, 2021

On September 3, Las Vegas Review-Journal reporter Jeff German was found stabbed to death outside his house in Las Vegas. Four days later, Clark County public administrator Robert Telles was arrested in connection with the crime. German’s critical coverage of Telles’s job performance was credited locally with contributing to Telles’s decisive loss in a primary in June mounted by a staff member from the office where German had reported on his misconduct.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.