My childhood best friend’s dining room hosted a suite of matching wood furniture: a tall glass-fronted sideboard; a table that stored its extra leaves below the surface, to be pulled out like drawers; chairs with open backs and black leather seats, all in a mellow amber tone. As she moved across the country, and up the West Coast, a coffee table moved with her, worth the trouble because, from the eighties to the aughts to the 2020s, it remained in style, as suited to a brick Colonial Revival home in Durham as it was to a PNW Craftsman.

This was intentional: From the moment such furniture appeared on American shores in the 1950s it was advertised as “address[ing] the needs of younger couples and new households, with its cleanliness of design.” Its “soft, rounded flowing forms” evoked the craftsmanship of an earlier era, while its “tapered lines” indicated to the world that you weren’t stuck in the past. While the style first drew attention in 1949 with a pair of chairs—the Chieftain, by Danish architect Finn Juhl, and the Round Chair, by Danish furniture designer Hans Wegner—when American manufacturers got done with it, you could buy a recliner, a stereo, a television, in still-desirable, still-salable Danish Modern. The authorship and by and large the artistry of the original chairs was effaced by the wave of cheaper, mass-produced copies, many of them made by American manufacturers, for American homes, with only the lightest sprinkling of Danish-ness.

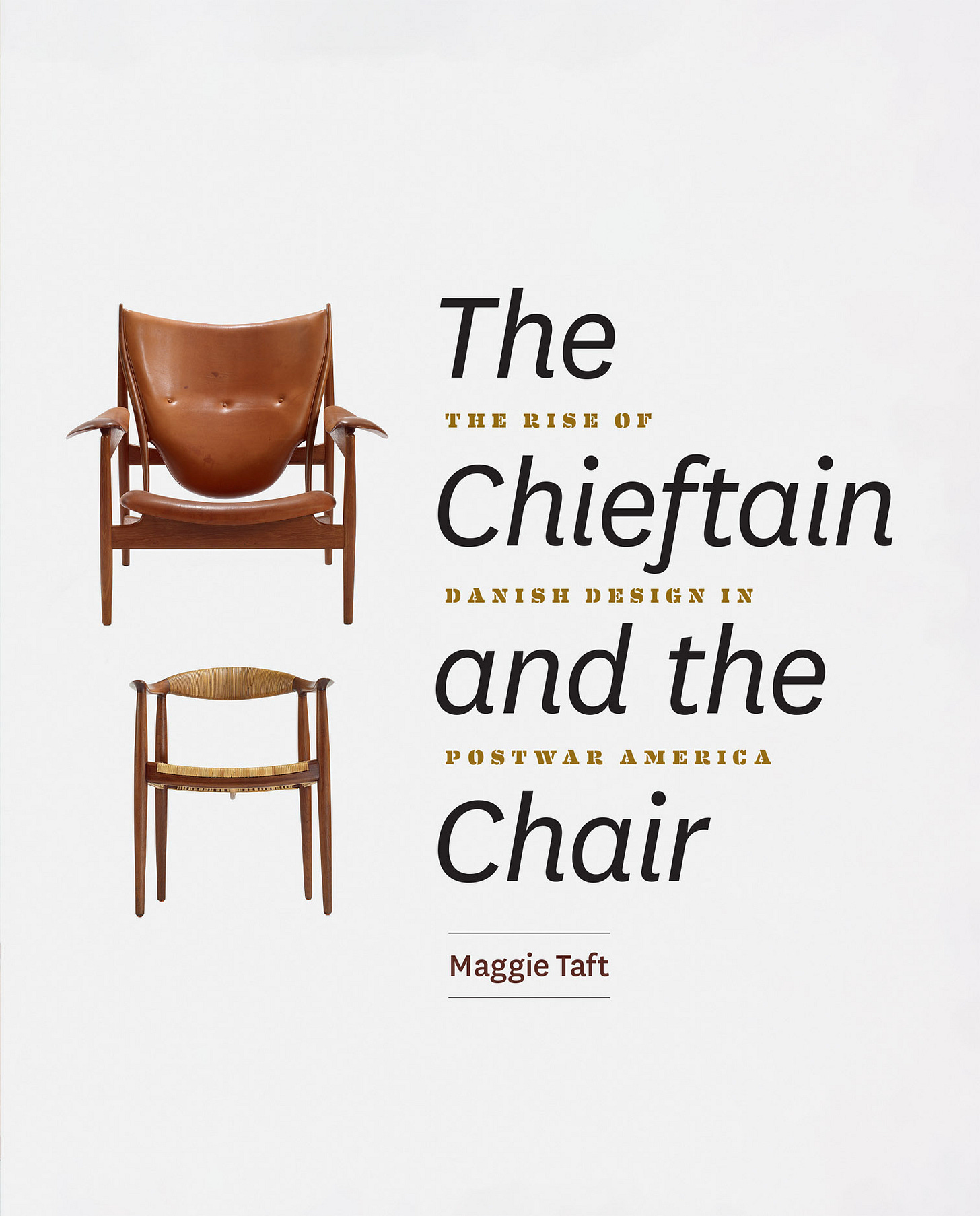

In her new book The Chieftain and the Chair: The Rise of Danish Design in Postwar America, Maggie Taft sets out to tell the story of how we got from the 1949 Cabinetmakers Guild Exhibition in Copenhagen, where Juhl showed his chair, with its shield-shaped back, next to a pinboard of influences including a bow and a photograph of an African hunter with spear (Juhl’s “romantic—and colonizing—view of primitive authenticity”) to the handsome, if slightly generic, coffee table in my friend’s living room. Her story is not one of heroic artistic choices, but of compromises made for manufacturing at scale, successive counterfeits, the dispersal of a once-original style. What persists from the two chairs of her title is the wood—initially teak—and a care to keep the joints smooth and the silhouette crisp. A previous generation of studies in design would have confined themselves to the original exemplars: the artistry of their conception, their innovations of manufacture, their influence on other museum-worthy chairs. But the age of the single-player design monograph is over (or should be), replaced by books like this, asking questions not about who made a specific charismatic design but what happens when it gets popular and shaped by commercial forces, what a label like “Danish Modern” even means anymore. Taft tells the story with quick, fluid prose and a plethora of period texts, photographs, and scenes, taking us from the craftsmanship of the Copenhagen Museum of Industrial Art’s Cabinetmaker Day School, where Wegner trained as a joiner in the thirties, to the TV appearance of a pair of Wegner’s chairs in the Kennedy-Nixon debate in 1960,

For the uninitiated—those who have never gotten down on their knees to look for a paper label or wood-burned maker’s mark, who have never searched Craigslist for “Eames style” anything, who don’t know teak from rosewood—picking up a book like this is to enter in medias res. You probably need to read one of those old-fashioned monographs, or take a trip to the Danish Design Museum in Copenhagen, a temple to chairs, before reading this book or one like Kristina Wilson’s recent Mid-Century Modernism and the American Body so that you will recognize the players and the narrative the authors seek to complicate. Both Taft and Wilson poke at the assumptions of largely white consumers: Wilson shows how such furniture was advertised differently in Black and white publications; Taft notes not only the faux primitivism of the “Chieftain” label, but that most of the teak so closely associated with Danish Modern actually comes from Thailand, which had signed a “treaty of friendship, commerce, and navigation” with Denmark in 1858 to avoid occupation by other European powers. “Thai Modern” might not have caught on then, but would now.

While I appreciated Taft’s dives into joinery, materials, and marketing for the mass movement Danish Modern became, the most fascinating chapter is her last, “Mail Order Danish Modern,” which takes on the fakes, an issue that continues to plague the makers of modern and contemporary furniture. House Beautiful, whose editor Elizabeth Gordon is the subject of another recent culturally-oriented design book, Tastemaker, called Wegner’s chair “the most stolen-from design in the world.” Knowledgeable fans of the style bought outright copies in Mexico, because they were cheap, while U.S. manufacturers like Lane and Basset and Stakmore “borrowed certain features common among Danish imports,” like wood, and splayed legs, and curved corners on an otherwise svelte form, spreading them across matching suites of furniture like my friend’s. Legal protections were tricky, since design patents were earned for decorative details of the type that would make any Danish designer shudder, and utility patents applied to technological innovation. Danish Modern, while easy to spot, had neither.

Taft doesn’t draw parallels to the present-day marketing of furniture, but they are right there for the taking. Scroll through the listings on Wayfair, a giant clearinghouse for suppliers, and you’ll see metal copies of Wegner’s Wishbone chair, leather-seated versions of the Round Chair, and all kinds of upholstered takes on Eero Saarinen’s Womb chair, which far surpassed the Chieftain in popularity as a comfortable, upholstered lounge without the puffiness of traditional furniture. What people are looking for in furniture now is remarkably similar to what people were looking for in 1960: Gordon described Scandinavian design as “human and warm … personal, national, and universal”— and even as we come to understand it as a cobbled-together construct, a little bit American, a little bit Danish, a little bit Southeast Asian, these chairs still look like a stylish place to sit.

Alexandra Lange is the author of The Design of Childhood: How the Material World Shapes Independent Kids and Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box, as well as free posts from time to time to those who follow us. Thank you for your subscription! Your payment supports our writers and our effort to build a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Please help us to grow our audience by giving Book Post to a friend, sharing this post, or cheering us on social media.

The book discovery app Tertulia is Book Post’s current partner bookseller. Book Post subscribers are eligible for a free three-month membership in Tertulia, providing a 10 percent discount and free shipping, among other benefits. Sign up here. Tertulia is offering other special deals for subscribers on books we have featured in Book Post: find out more here.

Curious about Notes? It is a messaging system available to Substack readers, including you! I wrote about it here and you can find me (editor Ann) on Notes here.

Book Post partners with booksellers to link to their books and support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens across the land. Book Post receives a small commission when you buy a book from Tertulia through one of our posts.

Happy owner of fake womb chair concurs that this cut-price perch is indeed a delightful place to sit and read this book review.