In the winter of 2019, The Paris Review ran an essay by Michael LaPointe entitled “The Racy Jazz Age Best Seller You’ve Never Heard Of.” The book in question, which first appeared in 1929, was Ex-Wife, by Ursula Parrott, who went on to write a score of potboilers with titles like Strangers May Kiss and Next Time We Live.

Published anonymously as a promise of something salacious, Ex-Wife was the story of a Boston bride, Patricia, who moves to New York, where she agrees with her husband, Peter, to allow themselves extramarital adventures. In the “era of the one-night stand,” jealousy, they agree, is “outrageously old-fashioned.” But Patricia soon discovers that Peter expects her to shrug at his infidelities while he turns vicious and violent upon learning of hers. He badgers her for a divorce while she, using sex as “anesthesia … against feeling so alone,” has a series of casual affairs. Of her lovers she says, “when, as occasionally, their desire was sufficient to break through the defense of my indifference, I was neither glad, nor very sorry.”

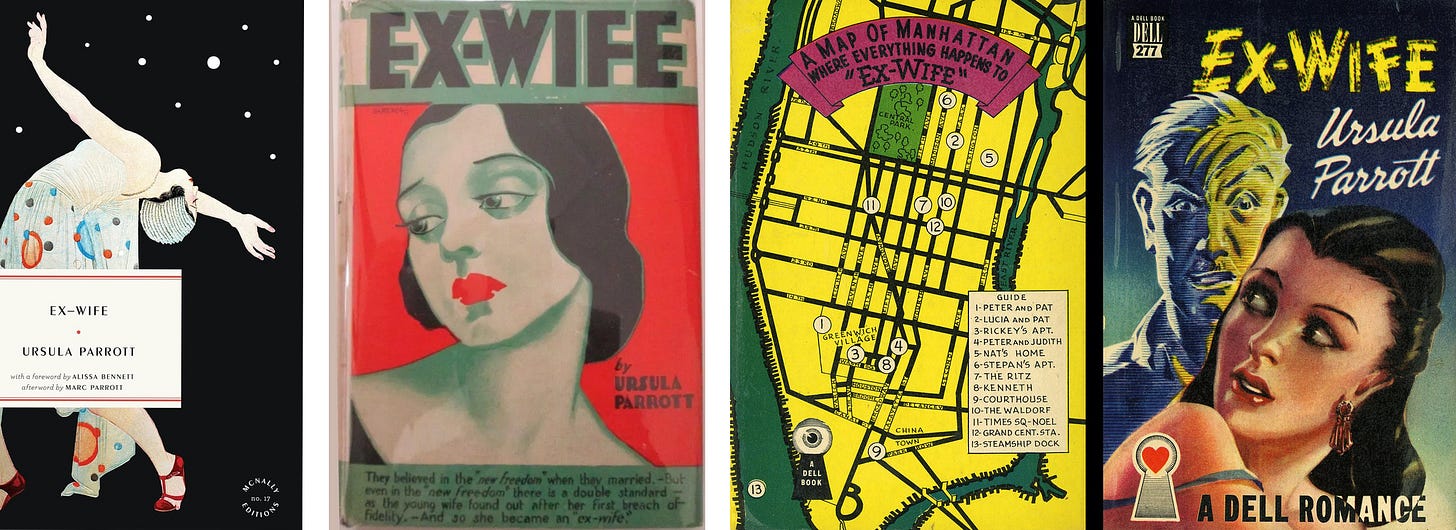

When LaPointe discovered Ex-Wife, it was already making its way back from more than a half century out of print. In 1989, Plume Books reprinted it in a series devoted to “lost” works by American women writers (the quotation marks were the publisher’s), with an introduction by Francine Prose, who noted Parrott’s “dead accurate ear for small talk” and was struck by how much “the characters sound as we do.” But its reputation remained confined to specialist readers until McNally Editions reprinted it again last year with an introduction by Alissa Bennett, who was struck by the “painful familiarity” of a book from the far past that seemed to “chart my own parallel romantic catastrophes.”

It’s no longer extravagant to speak of a revival. The book has been commended by, among others, Joyce Carol Oates in the New York Review of Books, Alexandra Jacobs in The New York Times, and Jessica Winter in The New Yorker. A biography of Parrott by Marsha Gordon was excerpted in Humanities Magazine, the official journal of the National Endowment for the Humanities. On the strength of Ex-Wife, she seems poised to join the pantheon of—till now, mostly male—Jazz-Age authors. Like F. Scott Fitzgerald, she wrote about young people under the shadow of the Great War who led lives of forced gaiety in fear that time was running out. “We have got through so much so fast,” says Patricia’s friend Lucia, “there can’t be much left.”

But why the resurgence of Ex-Wife, and why now? Now that open marriage and polyamory are having a chic moment, its subject would seem to be decidedly archaic : a young urban woman, in Bennett’s words, “lurching toward sexual revolution, but still psychologically tethered to Victorian morality,” and “caught in the freefall of collapsing convention.” Why should this dilemma hold interest at a time when it’s hard to name any convention prevalent enough to be eligible for collapse?

I think it’s because Parrott, a virtuoso in the art of conveying fluctuating moods, writes so well about bewilderment. Patricia, who calls herself a “futilitarian,” likes to recite this bitter conjugation: “I am futile, you are futile, we are futile, they are more futile.” She jumps from clever chatter to detached reportage to cries from the heart. At one moment, in the voice of detachment, she dismisses her anguish at her impending divorce as a vestige of the moralistic past: “It is so silly to mind. Just an incident in the career of a Modern Woman. What the hell!” But almost simultaneously she reverts to intimate candor, a transition that Parrott signals by shifting into parentheses “(I have stopped being detached. Something begins to ache horribly, in my heart)”. In the abortionist’s office, in divorce court, in a taxi where she clutches at a man she has just met (“animals huddled together for warmth”), she tries to persuade herself that she’s done with being callow, but then her counter-self speaks up again parenthetically: “I had lived long enough to get over being sentimental, at least I should have got over it. (I loved you so, Peter. Well, I do not love anyone else so).” Patricia’s voice vibrates between the tone of a jaded woman-about-town and that of a heartsick teen waiting by the phone for a call from her first crush.

Every recollection or anticipation becomes for her an enervating question, from the choice of wardrobe by which she hopes to win her husband back (“What to wear, the blue ensemble or Patou frock and black coat?”) to her self-interrogation about why she cheated on him in the first place. “Curiosity? Desire? The feeling that Pete experimented, and why should not I?” Feeling both titillated and demeaned, she roams through the sexual bazaar, where she is repeatedly sampled and discarded. Eventually, her cultivated coyness deserts her. In one horrifying episode, she is drugged and raped.

Ex-Wife takes place in what is often called Scott Fitzgerald’s New York—a glittering city, in Parrott’s words, whose “fragrance [is] blended of furs and tweeds and boutonnières and new leather gloves and French perfume.” But if Fitzgerald looked at metropolitan life through the eyes of a man savoring the sight of every beautiful woman with “all the wishing in the world” in her eyes, Ursula Parrott saw it through those very eyes—those of a woman assessed at every turn by men on the street, in the speakeasy, through the shop windows, and who knew how little time is allotted to her to make herself the object of their desire.

Beneath the brittle wit of Ex-Wife is the sad story of a woman pretending in public to relish her freedom while her private dream of a man igniting her life turns to ash.

Andrew Delbanco’s most recent book is The War Before the War: Fugitive Slaves and the Struggle for America’s Soul from the Revolution to the Civil War. He is Alexander Hamilton Professor of American Studies, president of the Teagle Foundation, which supports liberal arts education, and past president of the Society of American Historians. In 2022 he delivered the Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities on “The Question of Reparations: Our Past, Our Present, Our Future.”

Editor’s note: Ex-wife is published by the new-ish publishing imprint of the New York City bookstore McNally Jackson, devoted to reissuing out-of-print books from “off the beaten path, waiting to be rediscovered” noting that “rediscovery is what reading culture is all about.”

Are you signed up to participate in our My Àntonia winter reading group with

? We just started on Sunday, plenty of time to catch up! Scroll down to see the our conversation in the comments; we’ll have a Zoom gathering with Chris at the end to collect our thoughts. If you did not receive Sunday’s installment check account settings and toggle on “Fireside Reading.” Our partner bookseller Square Books is offering copies of My Àntonia at a discount (applied at checkout). Thanks, Square!Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box, as well as free posts from time to time to those who follow us. Thank you for your subscription! Your payment supports our writers and our effort to build a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Please help us to grow our audience by giving Book Post as a gift, extending your subscription by referring a friend, or sharing a piece you like.

Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, is Book Post’s Winter 2023 partner bookstore! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com. Read more about Square here in Book Post.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like.”

How sad that both Parrott and Fitzgerald died destitute and forgotten.

Both alcoholics, but Parrott sounds like a very different kind of person/writer than Fitzgerald, who was concerned with literary glory.

Parrott never wrote an "Afternoon of a Writer." Or did she?

Reading this fine review I was thinking of Edith Wharton and where Parrott might fit in that lineage of female writers writing about the place of women in society, money, and romantic entanglements, who wins and who loses. The pursuit of pleasure that for some is the pursuit of love or beauty that then becomes doomed in a way. Something like that! The category of ex-wife seems one that was just waiting to be given a literary life and Parrott it sounds like did the job more than admirably. I will read this book! Thank you!