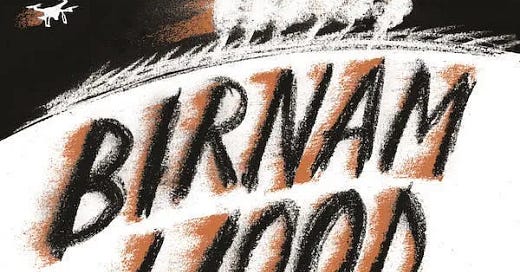

Review: Anthony Domestico on Eleanor Catton

Fun is a serious thing for Eleanor Catton, who won England’s Booker Prize ten years ago with a second novel that was both structurally complex and a legitimate page-turner, something you could include in a grad seminar or read on the beach. (I did the latter and would love to do the former.) In her first novel of 2008, The Rehearsal, an acting student i…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.