Once, when Werner Herzog was a toddler growing up in the Bavarian Alps in the last days of World War II, he was attacked by a witch: “On my right hand, I had a mark where the witch had bitten me.” I’m not sure that he believes this story—but I’m intrigued that he doesn’t see the need to question it.

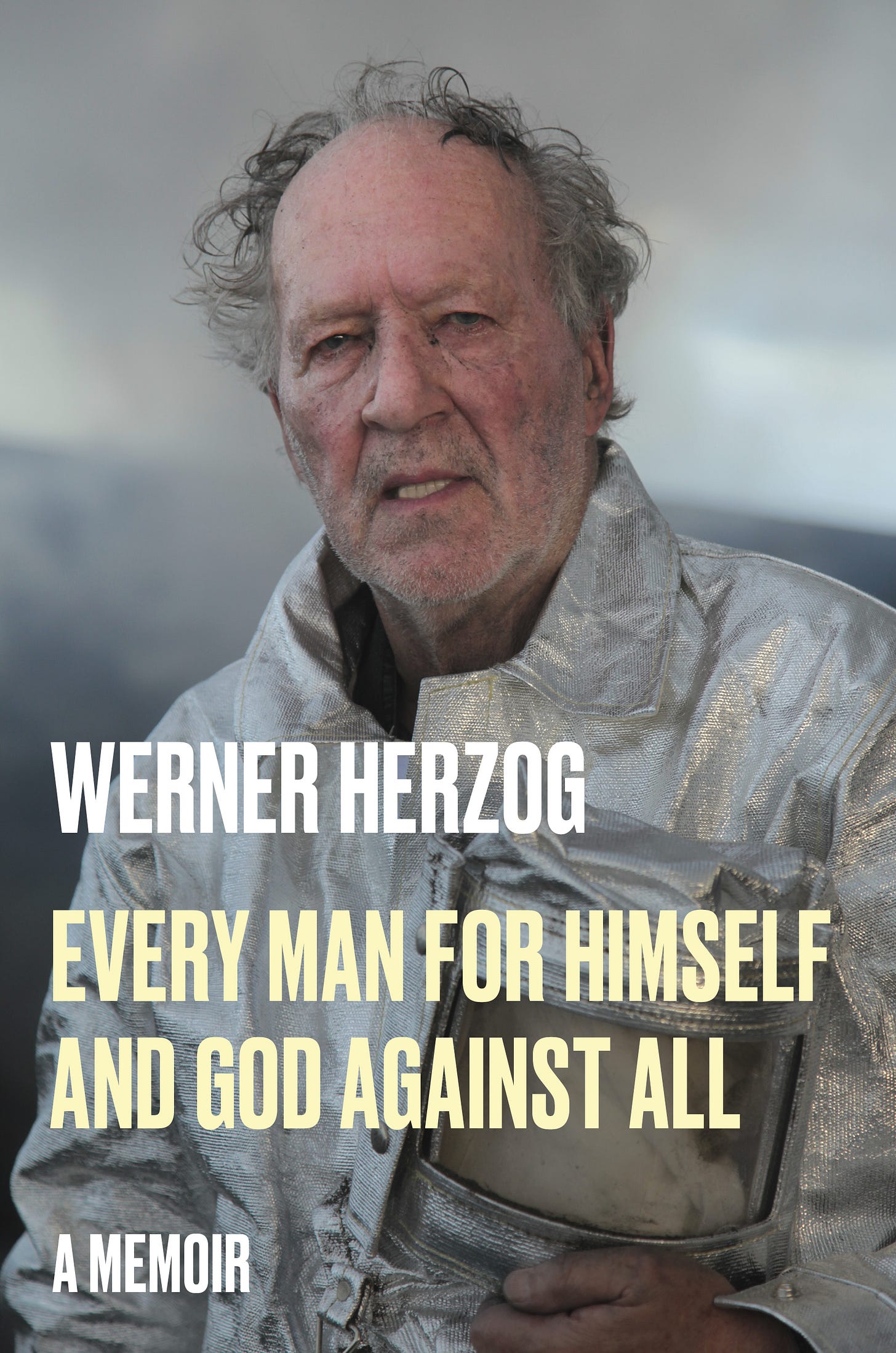

And that’s just twenty pages into his extraordinary memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All. In the three hundred or so that follow we experience a number of other curious episodes. We learn that Herzog made his first film with a camera he stole. He describes how he jumped into a field of cactus to fulfill a promise to one of his film crews. In the early 1960s, he recalls attending a Rolling Stones concert in the US:

When the concert was over, I saw that many of the plastic bucket seats were steaming. A lot of the girls had pissed themselves. When I saw that, I knew this was going to be big.

And he wistfully notes that Guatemala once denied him a visa—a pity, because he was “obsessed with the vague idea that I would help form an independent Mayan state in Petén. Word of this endeavor had reached me.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.