Review: Christopher Benfey on the Stevensons

An irreverent, pistol-packing, independent woman runs away from her “reliably unfaithful” first husband and throws in her lot with the always ill and self-described “flimsy man” Robert Louis Stevenson

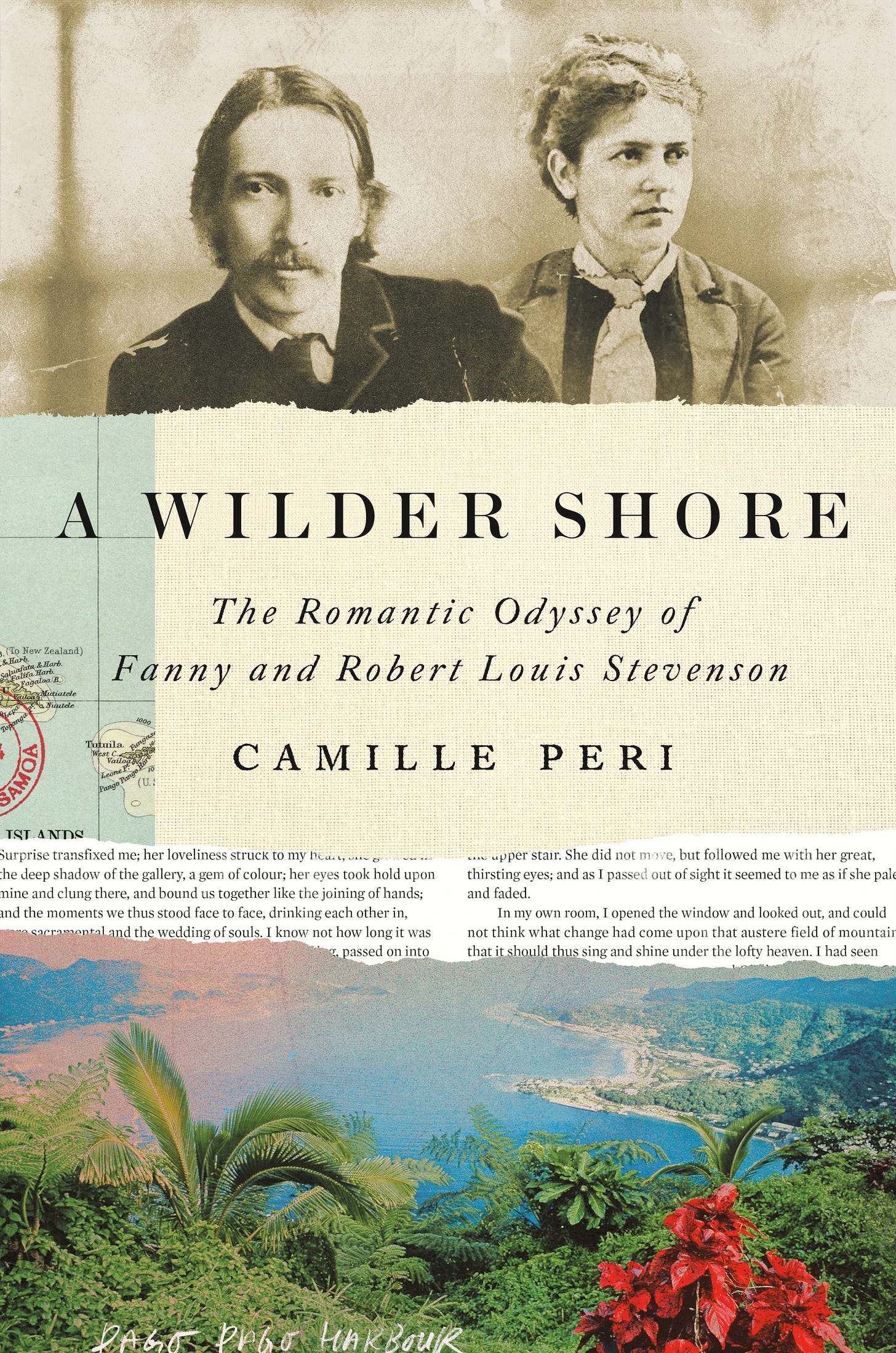

No character in his books—not Treasure Island’s Long John Silver, the one-legged pirate with the parrot on his shoulder, not the Janus-faced Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde—was more interesting than Robert Louis Stevenson himself, and none of his tangled plots was more amazing than his own life. That was the impression I got, at least, from Camille Peri’s lively and deeply researched double biography of Louis (as his friends called him) and Fanny Osbourne of Clayton, Indiana, with whom he shared his adventures. Peri makes a convincing case that Fanny was just as remarkable as Louis, an irreverent, pistol-packing, independent woman who ran away from her “reliably unfaithful” first husband in San Francisco and threw in her lot with the always ill and self-described “flimsy man” Stevenson instead.

Before Peri’s sympathetic narrative of their marriage there was John Singer Sargent’s sensational double portrait of Stevenson—longhaired, spectrally thin, a cigarette to his lips—striding away from a seated Fanny, barefoot and swathed in a sari, a darkened door enigmatically ajar between them. “The caged animal lecturing about the foreign specimen in the corner” was how Sargent explained the composition, which the Stevensons, oblivious to any intimations of friction, hung in their dining hall. One way to summarize Peri’s book is this: no one puts Fanny in a corner.

As a fellow Hoosier myself, I welcomed Peri’s detailed account of Fanny’s upbringing in the outback. Born Frances Vandegrift in 1840, she later changed her name to Van de Grift—“in deference to her seventeenth-century Dutch ancestors,” according to Peri, but I’d guess she thought it sounded more aristocratic. She was baptized by Henry Ward Beecher, an Indianapolis minister at the start of his own great career, around the time he and his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe, in neighboring Ohio, had their first encounters with the Underground Railroad.

Peri makes much of Fanny’s “olive complexion,” which inspired racist taunts at school and prompted rumors that her mother’s previous husband “might have been Fanny’s Creole father.” At sixteen she met a dashing rake called Sam Osbourne, private secretary to the governor of Indiana, married him the following year, and had a daughter, the first of three children, the year after that. Stir-crazy, Sam enlisted in the Union Army, saw no action, and fled to a silver-mining camp in Nevada to make his fortune, leaving Fanny, a habit with him, behind.

Realizing Sam could be depended on for nothing, Fanny in due course took their daughter, Belle, and two small sons, Lloyd and Hervey, to Paris where both women could study art at the height of Impressionism. A fellow classmate was Abigail May Alcott, the model for Amy in her sister’s Little Women. In the great tragedy of Fanny’s life, five-year-old Hervey died of tuberculosis. Worried about Lloyd’s health, she left the contagious capital for the artists’ colony of Grez, near Fontainebleau. It was there that the young Robert Louis Stevenson, with bad lungs (he described TB as the “wolverine on my own shoulders”) and a backpack, glimpsed her through a window. Apparently, they consummated their mutual passion in a canoe.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.