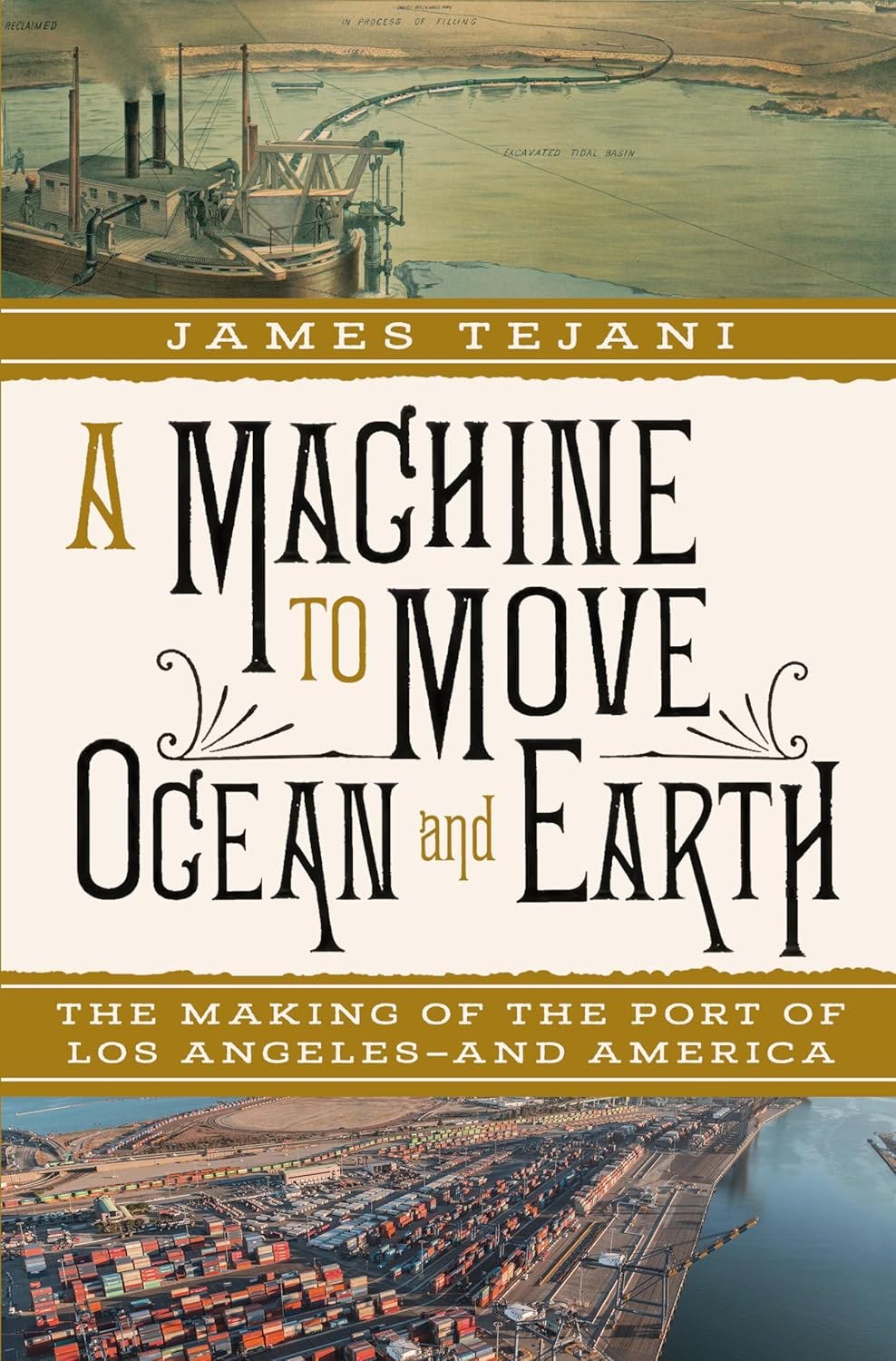

Review: David Alff on the Port of Los Angeles

LA’s port was an ambivalent achievement: a triumph of applied science, an ecological crime, a sublime public work promising collective uplift, and an occasion for greed, graft, and violence

On March 26, a Korean-built, Singapore-flagged, Danish-chartered, Indian- and Sri Lankan-crewed container ship struck Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge. The span collapsed, plunging eight road-maintenance workers into the Patapsco River. Of the eight men, who came from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, six died.

Debris blocked the channel,…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.