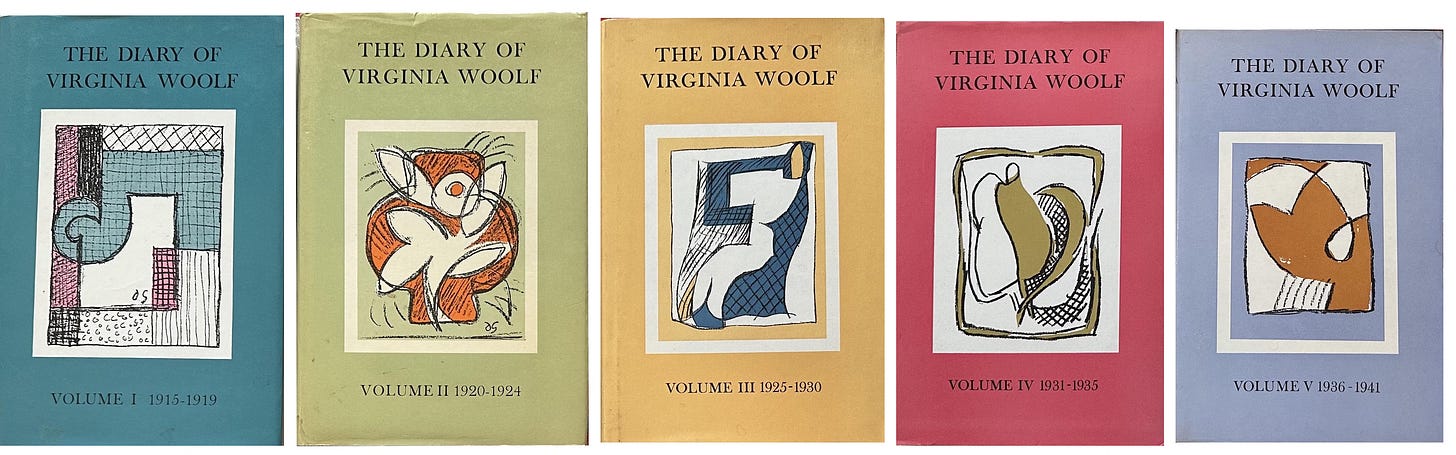

Review: Edward Mendelson on a new edition of Virginia Woolf’s Diaries

Virginia Woolf envisioned a diary that “coalesced” into something ”composed with the aloofness of a work of art.“ Have we done it justice?

The Diary of Virginia Woolf is a masterwork unlike anything else written by anyone in the past five centuries: the journal kept for twenty-five years as Virginia Woolf, with intense and unrestrained literary and moral intelligence, observes herself, her work, her marriage, family, and friends, and the wider worlds of nature, literature, politics, and war. Four years after she began it, she asked herself:

What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose knit, & yet not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace any thing, solemn, slight or beautiful that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some deep old desk, or capacious hold-all, in which one flings a mass of odds & ends without looking them through. I should like to come back, after a year or two, & find that the collection had sorted itself & refined itself & coalesced, as such deposits so mysteriously do, into a mould, transparent enough to reflect the light of our life, & yet steady, tranquil composed with the aloofness of a work of art.

This, from 1915 through 1941, she triumphantly achieved.

Writing at full speed, with no second thoughts or corrections, she records feelings and perceptions as acute as anything in her fiction. As in her novels, she values her aesthetic responses to the world while insisting on their moral and political resonance. Walking by the Thames in 1939, a few days after recording the end of the Spanish Civil War, she experiences

a rat-haunted, riverine place, great chains, wooden pillars, green slime, bricks corroded, a button hook thrown up by the tide. A bitter cold wind. Thought of the refugees from Barcelona walking 40 miles, one with a baby in a parcel.

Elsewhere, she writes about Milton in Paradise Lost, incidentally stating a credo about literature and its uses:

He deals in horror & immensity & squalor & sublimity, but never in the passions of the human heart. Has any great poem ever let in so little light upon ones own joys & sorrows? I get no help in judging life; I scarcely feel that Milton lived or knew men & women; except for the peevish personalities about marriage & the woman’s duties.

She writes about her marriage:

I daresay we’re the happiest couple in England.

About discovering her intentions in the act of revising:

I begin to re-write it [The Waves], & conceive it again with ardour, directly I have done. I begin to see what I had in my mind; & want to begin cutting out masses of irrelevance, & clearing, sharpening & making the good phrases shine.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.