Review: Geoffrey O’Brien on S. J. Perelman

From his first forays in the 1920s until the 1970s, preeminently in the pages of The New Yorker, S. J. Perelman refined and perfected a mode of comic writing of his own invention, a form that allowed him to conduct a continuing stylistic experiment. He was particularly drawn to the bizarre trivialities engendered by advertising agencies, movie studios, and other conglomerate entities, and his method of choice was to extrapolate their inherent absurdities to the limit. My earliest acquaintance with Perelman came through my father’s occasional loving recitation of favorite passages at the dinner table. What he relished most in Perelman’s prose was its capacity for setting in motion words and phrases and remembered voices and letting them collide like bumper cars, or ping pong balls, or perhaps atoms in a cloud chamber. Each collision was its own punchline and folded restlessly into the next, as in his 1944 “portrait” of playwright Arthur Kober—“I love his sudden impish smile, the twinkle of his alert green eyes, and the print of his cloven foot in the shrubbery. I love the curly brown locks cascading down his receding forehead; I love the Mendelian characteristics he has inherited from his father Mendel; I love the wind in the willows, the boy in the bush, and the Seven against Thebes. I love coffee, I love tea, I love the girls, and the girls love me. And I’m going to be a civil engineer when I grow up, no matter what Mamma says.” For my father, who did his share of ad libbing on his morning radio program, Perelman represented an ultimate ideal of unfettered improvisation.

Not all Perelman’s writing was so freely associative, but there was always the exhilarating sense that he could at any moment, if he chose, unleash a limitless store of tropes, catchphrases, fragments of old adventure novels and belle lettristic rhapsodies and high-pressure advertising copy, jingles and B-movie dialogue, generations of idle chatter and oratorical solemnity, and make his singular music with it. Anything that came to hand might serve as a point of departure: an ad for toothpaste, a soda fountain menu, a user’s guide to a tube of rubber cement, suggestions for Christmas décor in Mademoiselle, a story in Spicy Detective.

A page of Perelman could be a busy place indeed. He was by turns lexicographer, parodist, modernist collage-maker, and, not least, anthologist. Going far beyond mere illustrative quotation in his use of found materials, he embedded them in his prose and engaged in intimate and hilarious dialogue with them. The most purposeful of scavengers, he absorbed what he came upon and made it entirely his own. His sentences make up an immense comic dictionary of usage, dense with the layers and eras of language woven into them.

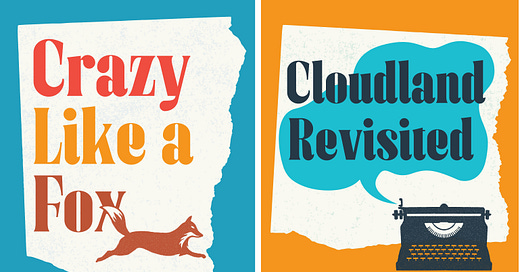

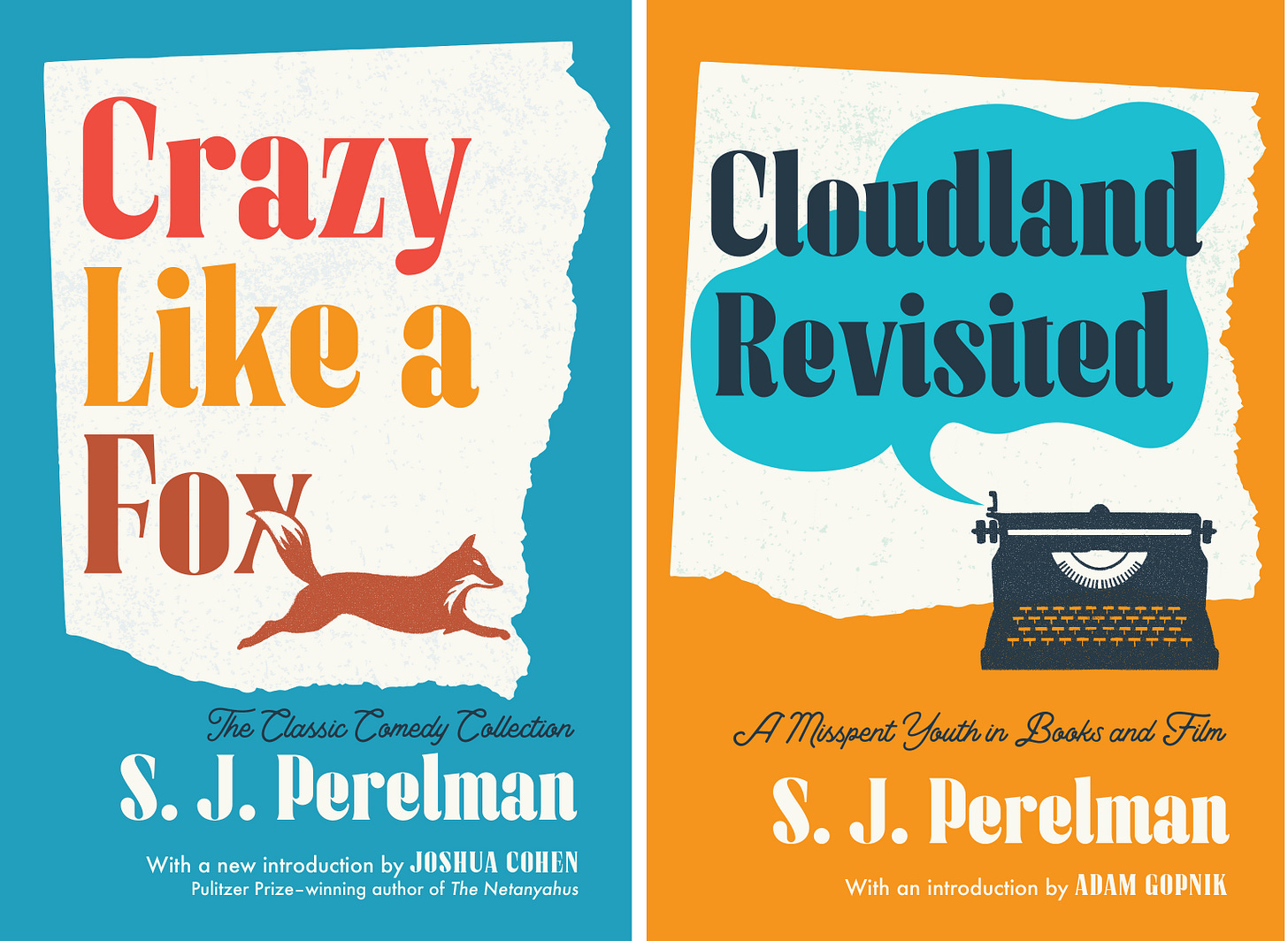

The Library of America, which a few years ago published a volume of Perelman’s selected writings, has now filled out his allotment with two paperbacks. Crazy Like a Fox (in its expanded version from 1947) restores to print the classic compendium of his best work from the thirties and forties, including the consummate parodies “Waiting for Santy” (Clifford Odets transposed to the North Pole) and “Farewell, My Lovely Appetizer” (Chandleresque private eye on the trail of a secret recipe for herring treats). Its companion publication offers something never before available in a single volume: the complete run of “Cloudland Revisited,” a series of twenty-two New Yorker pieces in which Perelman renews his acquaintance with books and movies that impressed him in the years between puberty and early youth—or, to put it otherwise, between World War I and the gaudy midpoint of the twenties. These were published piecemeal in the late forties and early fifties, but taken in one go they constitute a sustained comic masterpiece, a perfect convergence of style and subject.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.