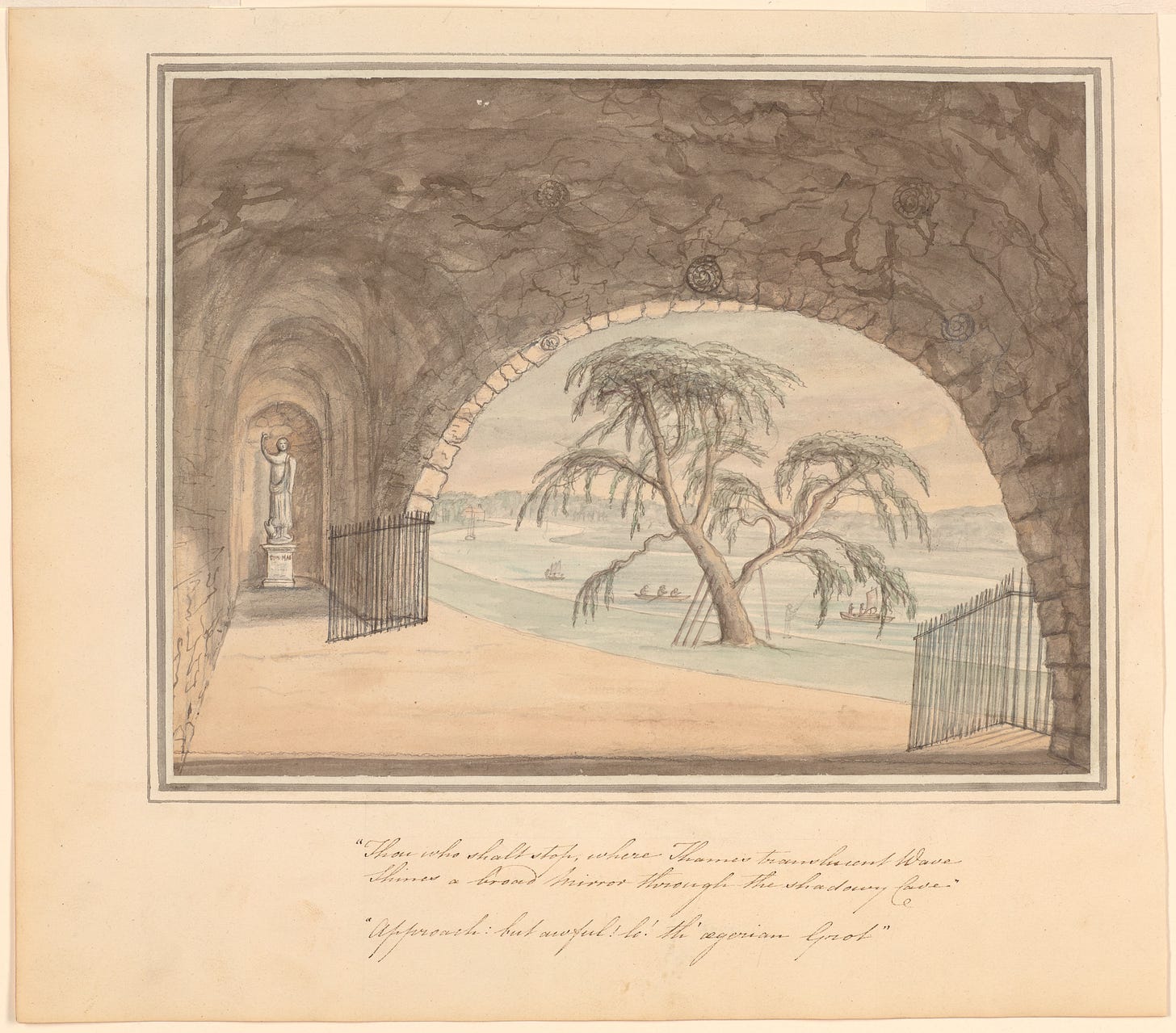

“View from Alexander Pope’s Grotto” (1800–1810) from an illustrated copy of The poetical works of Alexander Pope, Esq., Morgan Library. From My Dark Room (which cites a study dating the sketch to ca. 1760–1770)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.