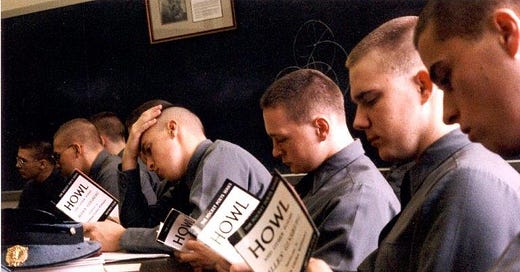

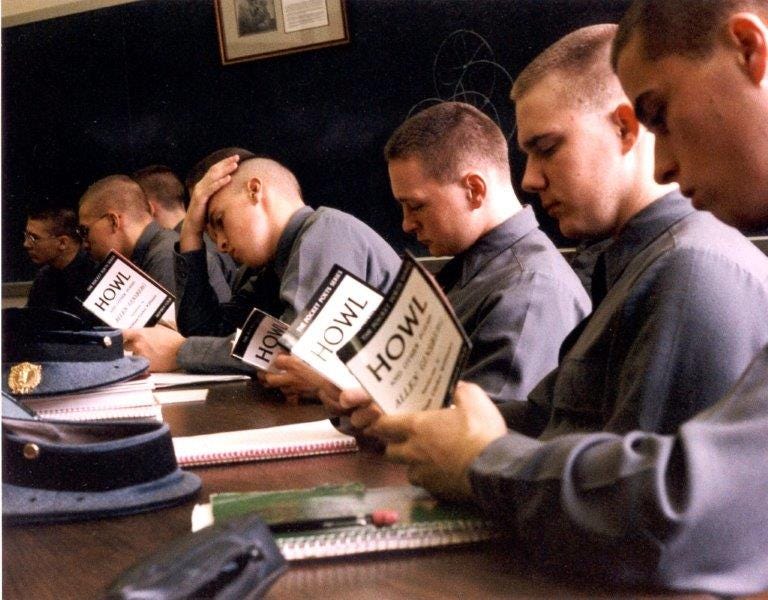

There is a photograph of a classroom at the Virginia Military Institute: The cadets sit in a row, all crew cuts and pressed gray uniforms. Their caps, bearing military insignia, rest before them on the desk. They are reading an assigned text for English class, each holding open a copy of a small book with a strikingly simple cover, black text against a white background. They look, to a man, bored out of their skulls.

This picture fascinates me, because the cadets are reading Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems. Published in 1956 by City Lights, Howl became the subject of one of the two most famous obscenity trials in the history of modern literature (the other is United States v. One Book Called Ulysses). Customs officials seized copies of Howl when they arrived from the printer in London; a bookstore manager was jailed for selling a copy to an undercover San Francisco cop; City Lights publisher Lawrence Ferlinghetti was arrested.

Wherefore this hullabaloo? Open Howl and begin to read:

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night …

It still razzle-dazzles today, this run-on prophetic mode of drug culture and madness, Whitmanian catalogue tuned to Blake-inflected beatific visionary blab with its own ideas about syntax:

Peyote solidities of halls, backyard green tree cemetery dawns, wine drunkenness over the rooftops, storefront boroughs of teahead joyride neon blinking traffic light, sun and moon and tree vibrations in the roaring winter dusks of Brooklyn, ashcan rantings and kind king light of mind …

But what got the Man’s socks in a twist was—of course—the sex. Apparently the line “who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists, and screamed with joy” was particularly objectionable. One wonders whether it was the fucking or the joy that was considered most scandalous. (In the pages of Partisan Review, Ginsberg’s straitlaced friend John Hollander decried “the utter lack of decorum of any kind in his dreadful little volume.”)

Anyway, everyone got off—er, everyone was acquitted. The judge in the case ruled that Howl and Other Poems “does have some redeeming social importance, and … is not obscene” (but let us not applaud judges too loudly).

Reading the lines in question today is a rather less dramatic affair, though not because we are so much more enlightened than our forebears. Howl confirms Fredric Jameson’s observation that the sexually explicit features of the “postmodern revolt” “no longer scandalize anyone and are not only received with the greatest complacency but have themselves become institutionalized and are at one with the official or public culture.”

What better image of this institutionalized complacency could be imagined than the assigning of Ginsberg’s verse to the nation’s future military elite, who—far from being scandalized by lines like “Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb” (from “America,” perhaps Ginsberg’s finest poem)—approach the reading with the dutiful ennui of students everywhere. Howl, like Ulysses and Lolita, has become homework.

And what Hollander (with disdain) called Howl’s “hopped-up and improvised tone” is now a default poetic mode. But the original remains a blistering critique of a sick society that remains sick—a total critique based, as Ginsberg put it in the lectures collected as The Best Minds of My Generation, on “that attitude of waking up in the midst of society and finding that everybody was crazy. It was all a mad scheme that was going to destroy everybody and nobody was going to get out alive.” This was hardly an uncommon vision in McCarthy’s mushroom-clouded America, but it was Ginsberg who constructed its most convincing poetic form.

Ginsberg published many more books after Howl—Kaddish (1961) and Planet News (1968) are especially significant—and became a countercultural icon, writing liner notes for Bob Dylan and performing with the Clash. What Jack Kerouac termed “the Beat generation”—as in “beaten down” but also “beatific”—is easily caricatured (my first exposure to the cliché of the goateed hipster reciting sophomoric verse over a jazz beat came from Looney Tunes), but the force of Ginsberg’s cry is undiluted: “It’s true I don’t want to join the Army or turn lathes in precision parts factories, I’m nearsighted and psychopathic anyway. / America I’m putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.”

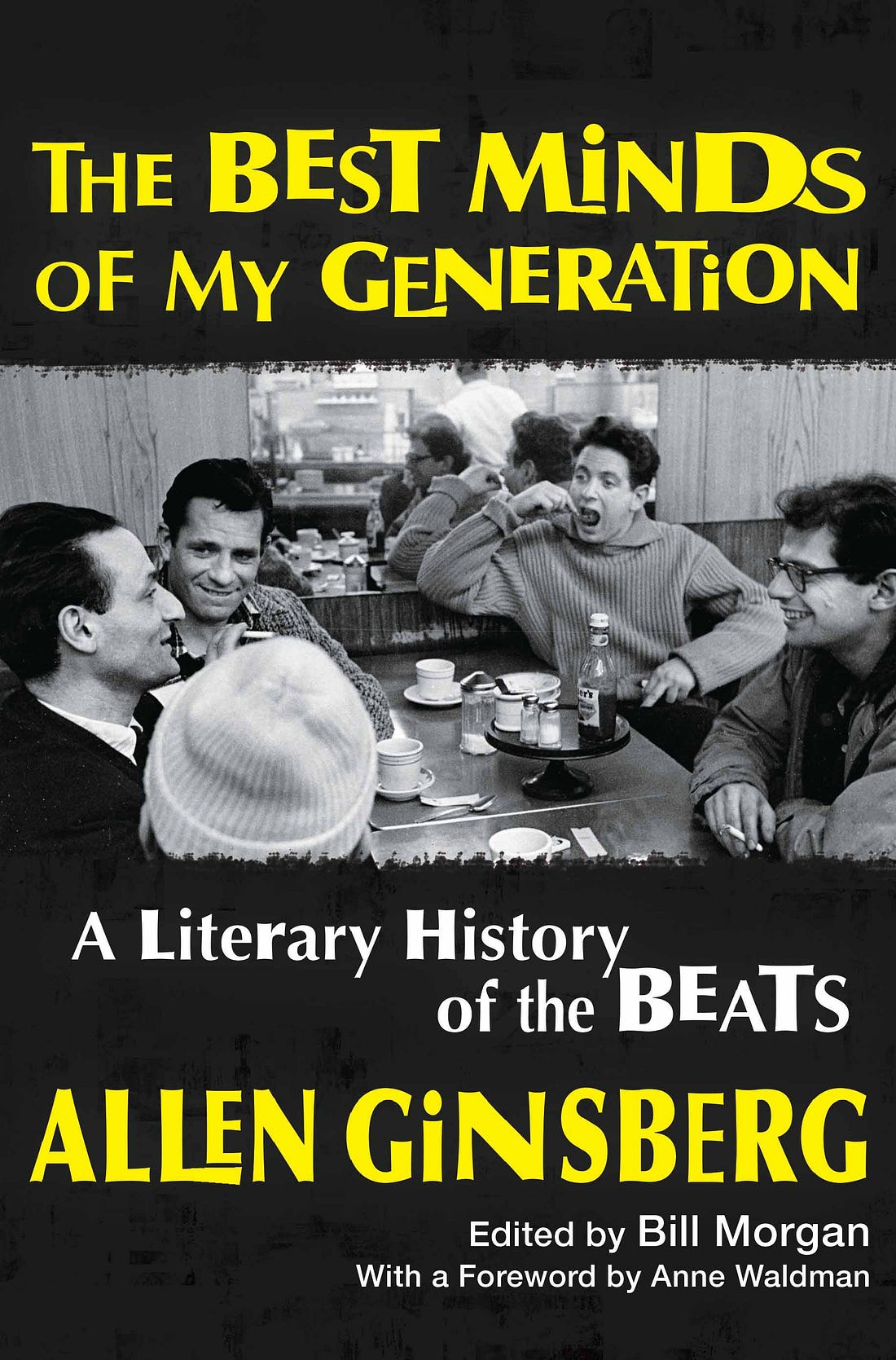

The Best Minds of My Generation: A Literary History of the Beats, a compilation of the classes on the literary history of the Beat Generation that Allen Ginsberg taught at the Naropa Institute and then Brooklyn College, compiled by beat bibliographer Bill Morgan, appeared in paperback this spring.

Michael Robbins has published two books of poems, most recently, The Second Sex. His book of essays, Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music, appears in paperback this month.

Book Post is in the midst of our Summer Vacation! We’re offering all our posts on the house. Starting September 4, our bi-weekly book reviews will be available via paid subscription, though we’ll offer a free treat every week or so to those signed in at bookpostusa.com.

Boulder Book Store in Boulder, Colorado, is currently Book Post’s featured bookstore.

Sign up to receive Book Post: Book reviews to your inbox bookspostusa.com

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, tell the author with a “like”