Review: Tracy Daugherty on Peter Matthiessen

When cataloguing a subject’s contradictions reveals more than the biographer intends

Biographers are strange creatures, presumptuous in proposing to tell another’s story, even when the subject wishes the story to remain unspoken. The presumption is perhaps greater when the subject is a writer, with a strong claim to articulating their own account of themselves. Yet biographers are also self-effacing, withdrawing behind the narrative to serve another as faithfully as possible. Often the nature of the portrait is in question: do we admire the subject more fully through knowing their circumstances, or see their flaws more clearly?

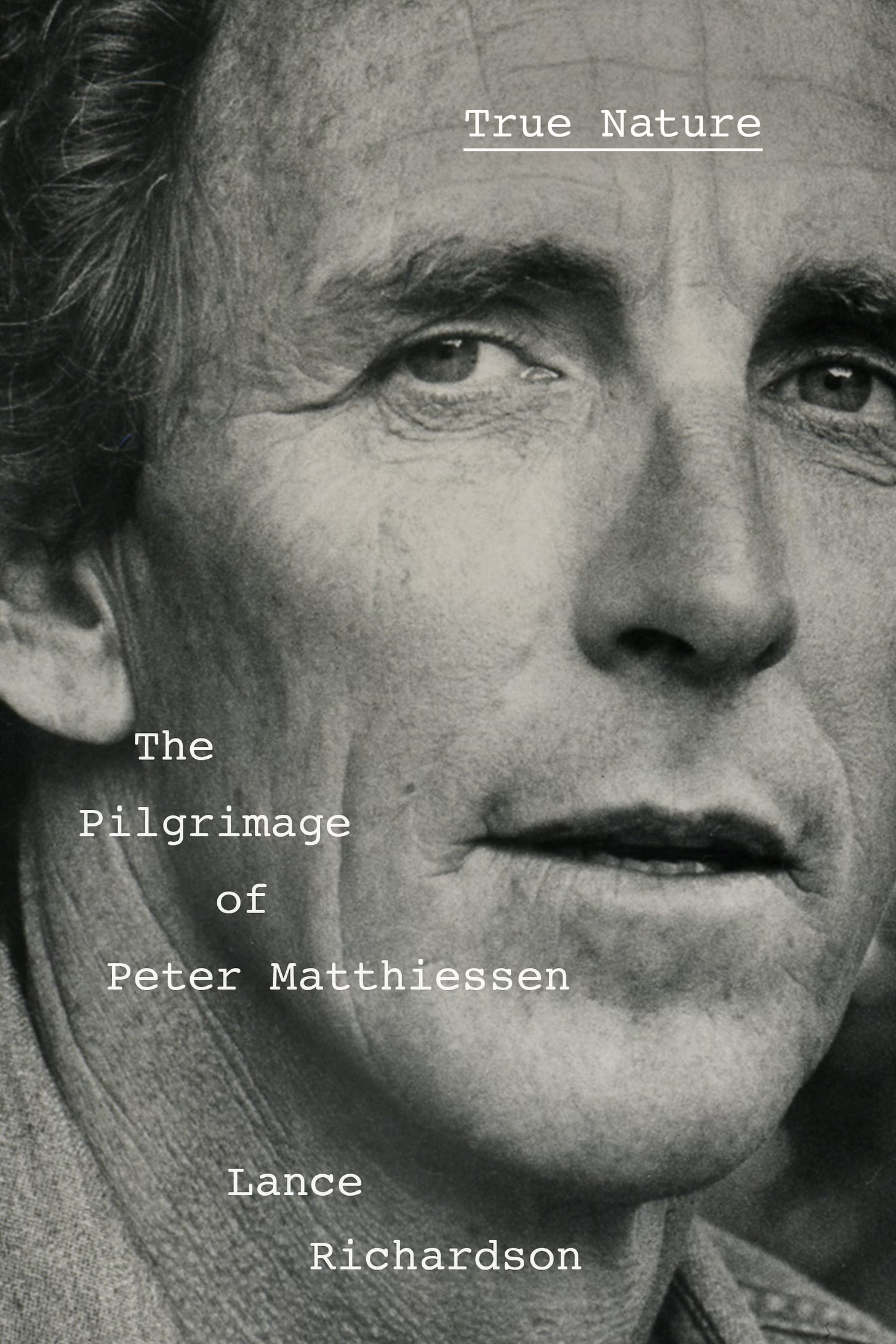

In True Nature: A Biography of Peter Matthiessen, Lance Richardson has written a solid, standard literary biography of Peter Matthiessen, author, activist, and esteemed man of letters. Richardson tracks his subject in a clear, deliberate chronological fashion, documenting every trip, every love affair, every book’s gestation and struggle across Matthiessen’s nearly nine decades. Persistent and lengthy footnotes attest to Richardson’s reluctance to lose any detail. He is a skilled and diligent writer, a ferocious researcher, passionate about his material and highly congenial to the reader. No such thing as a definitive biography exists, but reviewers will likely use the word “definitive” to describe True Nature. Still, Richardson’s straightforward treatment, however true to the facts of Matthiessen’s life, may ultimately deflect a piercing appraisal of who he was.

The book’s early pages are slow going. Matthiessen grew up privileged and spoiled, the son of an architect whose family’s wealth came from oil, zinc, and baleen. Initially, the young would-be writer is not very likeable. Richardson can do nothing to make him more appealing.

True Nature becomes more engaging as Matthiessen comes of age and reaches maturity. He wound up leading an extraordinary life, working for the CIA (Richardson is particularly good on Matthiessen’s clandestine years), traveling continuously to one remote location after another, becoming a Zen master, an environmental activist, a crusader for Native American rights, and one of his generation’s literary titans. He seemed always destined for a literary career, devoted to his writing even as he plotted more adventures. The adventures invariably ended up in his books.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.