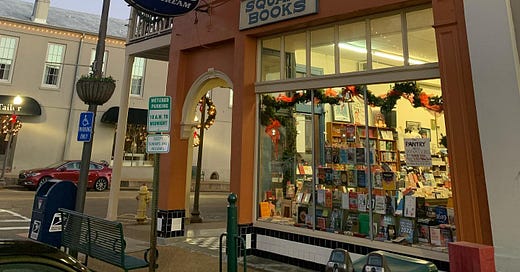

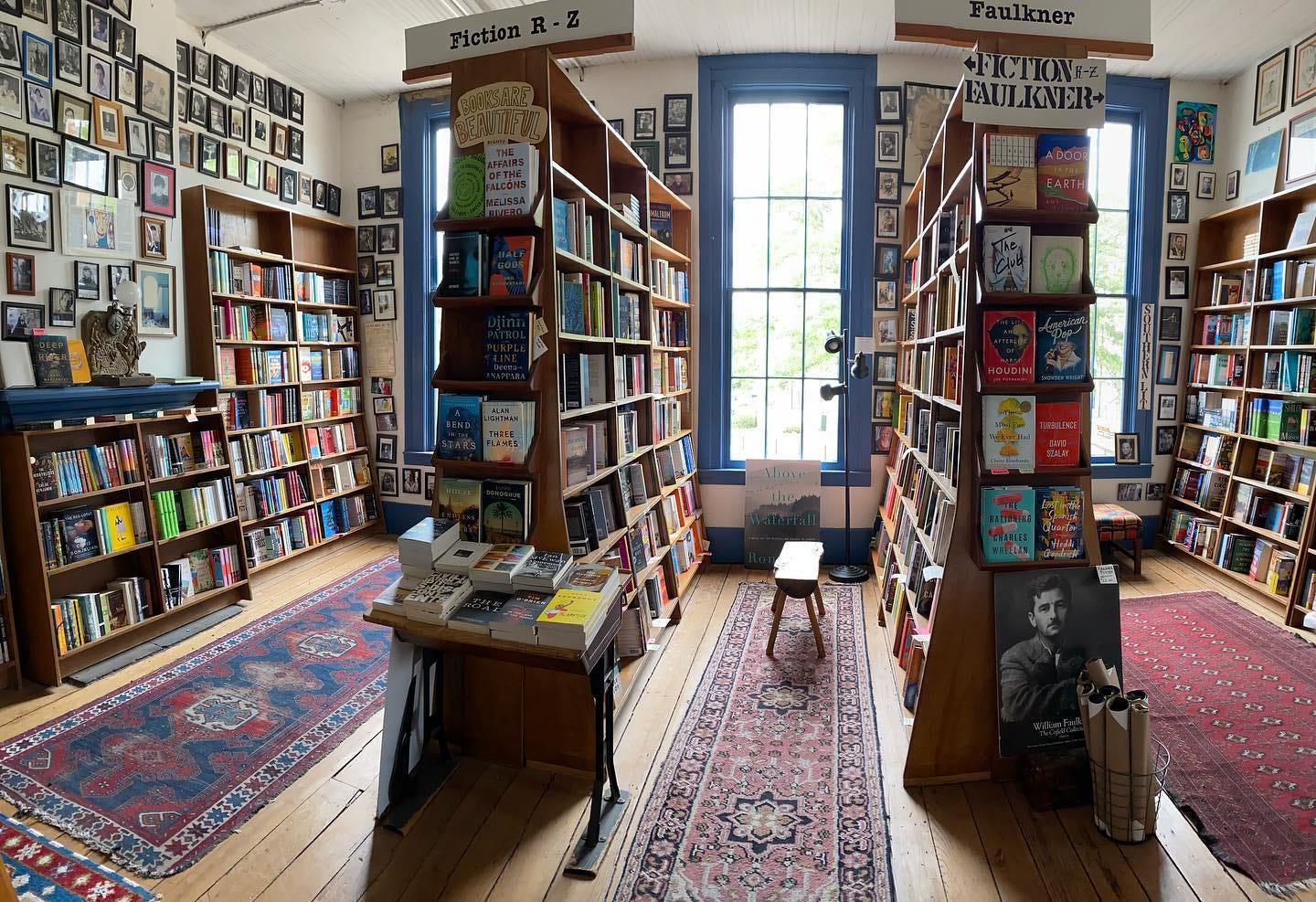

Square Books, its beloved balcony, and the eponymous square. Photos

When Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, was under consideration to be 2013 Publishers Weekly Bookstore of the Year, the Tennessee-bred publisher and one-time literary brat pack minder Morgan Entrekin wrote, “I am somewhat surprised to find myself writing a letter recommending that Square Books be selected as Bookstore of the Year primarily because I cannot believe it has not been selected before. Square Books is one of the greatest bookstores in America.” Square co-founder Richard Howorth, whose family had lived in Oxford for generations, first contemplated building a bookstore with his brothers as they watched tourists streaming in and out of William Faulkner’s house across the street growing up (Faulkner had died a year before his parents moved in). Oxford may be twenty-five miles off the interstate, and may like many towns have been withering on the vine in the sixties when Richard Howorth came of age, but it did house the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”) in addition to providing Faulkner with his “postage stamp of native soil.” Richard Howorth had heard that you could open a bookstore if you could find “at least twelve families—families of readers—who would buy books” within immediate range. He knew each of those families in Oxford.

Richard has also traced his impulse to start a bookstore in Oxford to a desire to redeem the town after the rioting with which it greeted James Meredith’s 1962 pioneering integration of Ole Miss. (Meredith gave his papers to the university days after rallies in the nineties over the school’s then-mascot, “Colonel Reb,” and unofficial banner, the Confederate flag, now both revoked. Richard has joined those calling for the removal of a confederate monument from the square.) Richard’s mother, the daughter and granddaughter of Ole Miss professors, knew the moment “meant ruin for the town and the university.” “To a large degree the community has supported Square Books as a way of demonstrating that Oxford is not the sort of place that it has been perceived to be,” he says, reflecting his own impulse back on the community. “Literature is one of the few things Mississippi can really be proud of,” he says. Author Kiese Laymon, whose books have chronicled his decision to return to his native Mississippi, has said that Square Books is “filled with literary tradition but also bubbling with a commitment to an innovative, much more radically kind literary south.”

Richard started the store with his new wife Lisa, who travelled to Oxford on a lark in a VW bus in 1968 after having gotten fed up with hippie California. Now inhabiting several comfortable old buildings with a broad balcony overlooking the town square, Square from the beginning combined the comforts of home with a taste for adventure and free-spiritedness. The store is “full of mismatched throw rugs and random sitting chairs, and every possible inch of wall space is taken up by books or photographs of the people who write them.” It sells “authenticated” pieces of its old balcony to defray the cost of its repair. When it opened a café between the history and fiction sections upstairs it was the first place in Oxford to serve espresso. The Howorths lured authors to Oxford with what became legendary conversation and hospitality, providing writers on the road with a comfortable room in their house with a desk and raucous dinners, helping engender for Oxford a “reputation as a cerebral but rowdy literary nerve center.” Last summer The New Yorker added richly to the extensive bibliography of Howorth lore with a dual portrait by Casey Cep that I encourage you to read for the vicarious pleasure of it alone.

Square’s literary trajectory got a big assist from the university’s creation, around the time the Howorths opened the store, of a Center for the Study of Southern Culture, headed by kindred spirit Bill Ferris, who shared the Howorth’s vision of a literary south in need of celebrating. The Howorths staged, for example, an “encycloparty,” described by Casey Cep, announcing the Center’s thousand-plus-page Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, with “dozens of contributors … dressed as entries.” Square Books sold hundreds of copies, advertising them as a bargain at $5.98 a pound. Ferris helped to bring to town such writers as Toni Morrison, Allen Ginsberg, Alex Haley, and Alice Walker, eventually installing as writer-in-residence prodigal Southerner, former Harper’s editor, and legendary writers’ champion Willie Morris, and later Barry Hannah, who drew in their own circles of friends and proteges including William Styron, James Dickey, Richard Ford, Amy Hempel, and Donna Tartt, alongside home-grown Larry Brown and civic booster John Grisham.

I’m reminded of an essay I read recently about how when Craig Rodwell and friends founded the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop in Greenwich Village in 1967, by putting “books by queer authors on the same shelf, they redefined the meaning of homosexuality. It was no longer simply a deviance or a disorder. It was, instead, a coherent category—with shelves of books to prove it.” Putting books side by side, bringing writers into conversation with readers, opens forms of shared experience without delimiting them. In the years after the Howorths launched Square in Oxford and gave public face to Ferris’s academic project, critics began taking note of a resurgence of Southern literary energy, like the creation in the eighties of Algonquin Books, drawing on what co-founder Shannon Ravenel described as ''a lot of good writing, particularly fiction, [that] was having a hard time breaking into the New York publishing scene.” The town’s identification with Southern literary culture was so potent that a second defector from California whose road trip petered out in Oxford, Marc Smirnoff, founded what became a signature Southern literary institution, naming it for the town, after working a while behind the register at Square (the last of a series of bookselling stints): the magazine The Oxford American. “This town is suddenly overrun with poseurs," fretted a local litterateur in 1997.

To step into Square Books may have the feeling of something particular to its place and a few very original people in it, but Richard Howorth’s vision extends to the big picture and has been prophetic of our present cultural challenges and the benefits that bookselling and other local cultural institutions can bring to meeting them. From the beginning he sensed that places like Oxford were imperiled and that their fragility was a threat to civic life. Way back in back in 2000, Rob Gurwitt wrote of Square, “It is hard these days, when so much of the commercial life of our communities takes place in malls well outside the center of town, to understand just how deeply a town square can be embedded in the gut of a place … As chain retailers and others began arriving in town, though, the square’s life began to ebb, as it did in most other Southern and Midwestern towns … by the late 1960s it looked like the square’s best days were over.” That the Howorths named their store after the square was not just a geographic marker, it was a statement of purpose. “Square Books became a destination—a well-lighted, comfortable refuge on one of the square’s main corners where townspeople could meet.” Gurwitt goes on, “If over the last decade Oxford has become a signal destination for travelers to the Deep South … that would be in some measure due to that store.” “Square Books gives people a reason to come to the square,” a gallery owner on the square told a Chicago Tribune reporter writing up Oxford as a destination in 1997. I’m reminded of how Malaprop’s, our Fall 2020 partner, helped turn Ashville, North Carolina, from a faded, boarded-up resort into a bustling destination. In 2017 reporters from the Huffington Post visited Oxford as part of a multi-state bus tour, “Listen to America,” at Richard Howorth’s urging. He told the organizers “You know, this place just works, and people here know how to work together and how to get things done and move things forward.” The Huffington Post reporters said that was “a really different story than what we’re hearing at a lot of places we’re going to.”

Richard Howorth eventually became a president of the American Booksellers Association (ABA), a mayor of Oxford, even a board member, during the Obama administration, of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the New-Deal era utility envisioned as an engine for economic recovery in the rural South. Each of these roles represented an extension of his vision for the life of the square. As president of the ABA, Richard helmed a prescient lawsuit against the big chains for securing advantageous terms from publishers and distributors, using arguments that have been revisited in a recent a class-action lawsuit on behalf of independent booksellers against Amazon; the Association successfully opposed a merger between Barnes & Noble and the distributor Ingram; and Richard pushed for the kind of shared web presence for independent bookstores that finally came to full fruition only a few years ago with Bookshop.org. He understood not only that vitality in independent bookselling leads to health in the book industry and more people reading, but that, as Rob Gurwitt put it in his 2000 profile, “the dangers posed to [independent retailing] by superstores and online sellers don’t just threaten some quaint form of distributing goods, they imperil the fabric of neighborhoods and towns. For good or ill, stores—their bearing on the street, the people they draw in, the presence they cast in the community at large—help define their neighborhoods, which is why the changes buffeting traditional retailers are not solely fodder for the business pages … the quality of our daily lives, and of the places we choose to live, is up for grabs as well.” Of his run for mayor Richard told Rob Gurwitt, “our problem in Oxford was the increasingly insecure future of the square as an economic unit. And Square Books represented a small, modest investment in the future of the square.” In a most-recent iteration of this vision, Richard published this year an opinion piece in The New York Times opposing the merger of mega-publishers Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster, writing “What I worry about are the writers and books that will not get published or could be otherwise marginalized because of this even greater concentration of power.” In the story of Square Books, the value of the public square as a safeguard of civic life, and the value of the independent bookselling as a safeguard of reading and intellectual life, come together.

In its “Exercise Your FReadom” section, the Square Books web site notes that three of the most frequently challenged (and most accomplished) of the contemporary challenged-book authors are from Mississippi: Jesmyn Ward, Kiese Laymon, and Angie Thomas. (Also on the list is Margaret Walker, whose work we considered a few weeks ago.) All three have appeared at Square Books within the last two years, Jesmyn Ward in a sold-out event three weeks ago. Jesmyn Ward and Kiese Laymon both made the decision to return to Mississippi, in spite of formidable obstacles, as a commitment to their home and its literary life and future writers. Jesmyn Ward: “Even as the South remains troubled by its past, there are people here who are fighting so it can find its way to a healthier future”; Kiese Laymon: “I pledge allegiance to the Mississippi freedom fighters who made all my pledges possible. I pledge allegiance to the baby Mississippi liberation fighters coming next,” and of his Oxford neighbor Square Books, “they love readers even more than they love books and they’re always doing creative things to get more of Mississippi reading, writing, and communing over what we’ve read and written.”

Richard Howorth was elected mayor twice in a town that is equally divided between the political parties. He has created a store a with “large and diverse inventory” that “encourages people from all walks of life, both as readers and writers.” Square has included remainders since its opening, and used books since the late 1990s, to appeal to bargain book customers. “There are lots of opportunities for bookstores like this one to succeed. There are a lot of underserved markets,” Richard has said. There are many Oxfords waiting to be born. Quoting a note of encouragement he received from a book veteran when the store opened: “Bookstores grow where their owners want them to.”

One can see in this enterprise, built to survive and thrive with its neighbors, how love—love of literature, of readers, of home—can make one particular family, one particular town square, something large enough to contain a place’s wounds as well as its joy, its inventiveness, its aspirations. One can see in Square Books how bookselling is a kind of hospitality—even a model of hospitality—that makes room for every soul and feeds it what it needs to shine. Now, more than ever, it’s what our country is aching for.

Give a Book Post Book Bag! A year of Book Post and $25 worth of books from Square Books, including a 10 percent discount.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Book Post reviewers include Adrian Nicole LeBlanc, John Banville, Álvaro Enrigue, Reginald Dwayne Betts, and more.

Square Books of Oxford, Mississippi, is Book Post’s Winter 2023 partner bookstore! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.