Notebook: (2) Translation

We depend for translation on small publishers operating on the near side of ruin most of the time

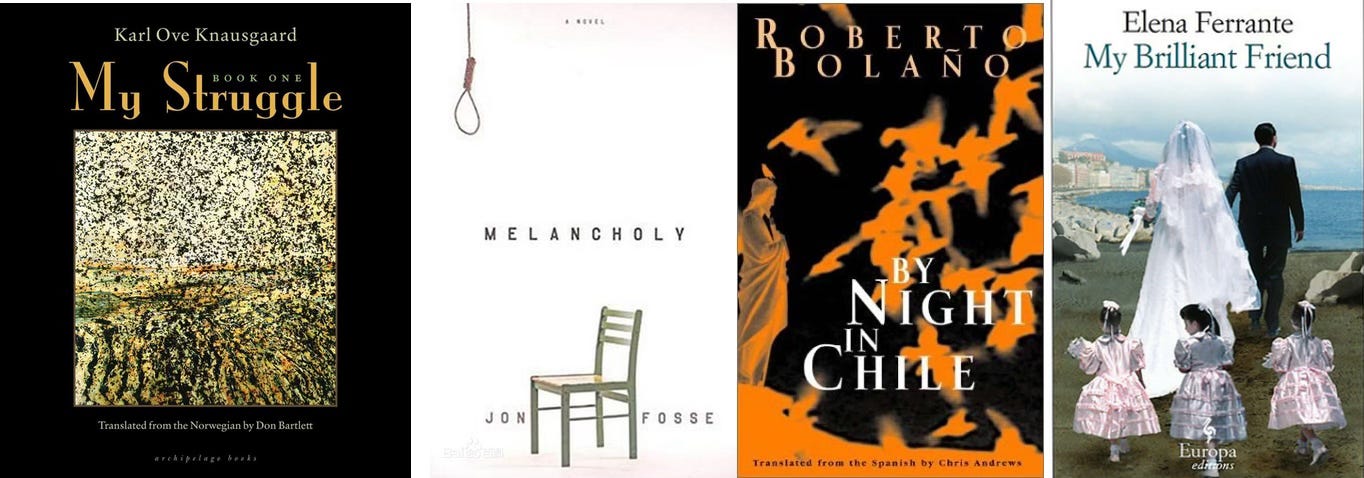

First US editions of Karl Ove Knausgaard (2012), Jon Fosse (2006), Roberto Bolaño (2003), and Elena Ferrante (2012), from Archipelago, Dalkey Archive, New Directions, and Europa publishers, respectively, all still independent

Read Part One of this post here

A swelling suspicion of foreignness in the early 2000s (remember “Freedom Fries”?), reinforced by the increasingly commercial imperatives of a consolidated publishing industry coalesced with new technologies to prompt an efflorescence of smaller publishers seizing the opportunity to publish international writing, often with financial support from its home countries: New York Review Books in 1999, Archipelago in 2003, Other Press, which began publishing literature in 2004, Sandro Ferri’s Europa in 2005, Chad Post’s Open Letter in 2008, New Vessel in 2012, Deep Vellum, The Center for Translation’s Two Lines Press, and Restless Books in 2013, and Transit Books in 2015. Smaller publishers looked to translation of major writers not being served by commercial publishing as a way to build a substantial list. Then-director of Graywolf Press, which would become one of the most august of the independent publishers, Fiona McCrae, said in 2008, “Philip Roth is not going to suddenly be published by Graywolf. So you see who is the Philip Roth of Italy or who is an interesting writer out of Sweden.” She echoed a story publishing legend Carol Brown Janeway passed on about her former boss Alfred Knopf, that he told her he first published translations because American authors would not appear with a Jewish publisher.

In 2003 the revered translator Michael Henry Heim made a bequest of $734,000—the benefit his mother had received when his Hungarian émigré father was killed while serving in World War II, and all its subsequent earnings—to PEN to create a fund to support translation into English. It was the largest single donation the organization had ever received. The translator Esther Allen, who worked with him to create the fund, wrote that he was motivated by “concern about the vast structural imbalance between the Anglophone sphere and the rest of the world” in literature and publishing.

By the teens the tide was beginning to turn. Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo spawned a worldwide boom in Scandinavian crime fiction in 2008 and 2012 saw the beginnings of years of international success for the serial works of Elena Ferrante and Karl Ove Knausgaard (first published in English by Europa and Archipelago). In 2016 the International Booker Prize was adapted to reward a single novel rather than a writer’s career and to split the award between the translator and the author. In 2018 the National Book Award reinstated its prize for a work of translated fiction, and The Atlantic declared international writing to be “the hottest trend in the American literature.” (Author Liesl Schillinger noted as a possible contributing factor the number of rising American writers born outside the US, including Chang-Rae Lee, Edwidge Danticat, Jhumpa Lahiri, Gary Shteyngart, Khaled Hosseini, and Junot Díaz.) Growing MFA programs were offering professional harbor to translators. In spite of all the new publishers and supports, though, the totals on the Translation Database barely budged. Chad Post wrote in Publishers Weekly that 2018 was the second year in a row that the number of published works in translation declined from a high in 2013, and they have continued to go down. (Publishers Weekly discontinued the database in 2023.) An Author’s Guild study released in January showed that 63.5 percent of literary translators make $10,000 or less a year from translating, twice as many as in a comparable study in 2016, and only 11.5 percent of respondents reported earning 100 percent of their income from literary translation work.

The prominence of work published by smaller independent presses—translated and otherwise—that wind up on prize rosters underlines the importance of their role in the culture. Noting that the International Booker Prize longlist of thirteen books for 2019 had only two from major publishers, judge Maureen Freely told The Guardian that “the really good independents have become the cultural talent scouts.” Chad Post wrote in 2023 that “of the sixty presses/imprints that have published the most translations between 2008 and 2022, only eleven are from the Big Five” consolidated publishers.

We may lament that translators are not better paid, and there are not more translations available, but these independent publishers are operating on the near side of ruin most of the time. Chad Post and Anne Trubek of Belt Publisher have described in harrowing detail how the economics of print production, warehousing, and, particularly, distribution, make it nearly impossible for any but the most tiny (person in the garage with a laptop) or the most huge publishers to cover their expenses selling books. Big Five publisher Simon & Schuster argued in court that it could not survive on its own. Small publishers who try to make a go of it without seeking nonprofit status and donations argue that they want to be answerable to readers rather than donors. Both Chad Post and Anne Trubek anticipate some major change in the way books are manufactured and sold if readers are to have access to physical books other than the small shelf of commercially invulnerable product produced by the Big Five, who control 80 percent of the contemporary book market. Bookseller Sarah McNally asked in a panel how readers are going to find out about new writers outside the commercial mainstream with constricting sources of book news (our raison d’etre). Chad Post discussed with the book influencers Tony P. and Andrew Merritt on the “Life on Books” podcast that viral Instagram and TikTok posts shared by like-minded readers are becoming a significant source of sales for translated literature. In an essay in The New Yorker about UK independent publisher Fitzcarraldo—four of whose writers, in its short ten years of life, have earned Nobels—Rebecca Mead cited a study showing that almost half of fiction in translation in the UK is bought by readers under thirty-five.

I wish the “data humanists” would have at these figures. I would love to know what percentage of published books, and what percentage of publishing earnings, have come out of Big Five vs. non-Big Five publishers over time; what share of American books are translated, measured per unit and in earnings, over time; what share of translated books and all books are sold by independent booksellers, by online retailer[s], and direct to customers. How many total books and translated books are sold via social media? To what extent have government programs—such as the NEA’s support of book distribution in its early years and its grants to translators and the generous state support that has made Minnesota a haven for small publishing—enabled translation, year to year? Has the proliferation of small publishers and support for translators at all expanded access to translated work? Has it done so on the backs of near-volunteer labor by small publishers and translators—i. e., are survivable margins possible in the current environment?

Looking ahead, Alex Shepherd and Mark Krotov ask whether the blockbuster-driven conglomerate system can support “many Kangs, or [2022 Nobelist Annie] Ernauxs at once. The publishing industry is not currently constructed to cultivate or promote authors who are doing the kind of work the Swedish Academy seemingly wants to highlight.” Translation legend Edith Grossman has eloquently described the extent to which all literature, though it may be bound by language, exists in extra-territorial space. There would be no García Marquez without Faulkner, or Kafka, who came to him by way of Borges. To interrupt this circulatory system is to deprive literature, and with it the growth of our inner life, of oxygen. The fate of translated literature is both a register of and a contributor to our cognitive health. These momentous autumn weeks expose to an iron glare the consequences of intellectual and spiritual isolationism, and the ruthless mercantilism that smooths its path.

Ann Kjellberg is the founding editor of Book Post. Read more of her Notebooks on publishing, bookselling, and the book life here.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Our recent reviews include: Joy Williams on the hidden Russian modernist Andrey Platonov; Michael Robbins on the perils of translating Ovid, Barry Yourgrau on the policiers of Jean-Patrick Machette.

Dragonfly and The Silver Birch, sister bookstores in Decorah, Iowa, are Book Post’s Fall 2024 partner bookstores. We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

If you liked this piece, please share and tell us with a “like.”

Thanks so much Ann for highlighting the inspiring and vital role of indies and translation. The university presses have also long supported translation- fiction and nonfiction and poetry- as part of our mission to engage globally. Grateful to be standing up with Independents in this enthusiastic commitment. Also want to shout out to Seagull books for their vital translation work and history.

I’ve actually been on a Scandi noir tear, planning to pitch you a Notebook entry about it.