Announcing Our Fall Partner Bookseller: Chicago’s Pioneering Nonprofit: Seminary Co-op and 57th Street Books (Part One)

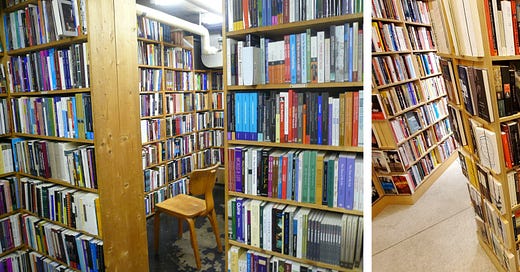

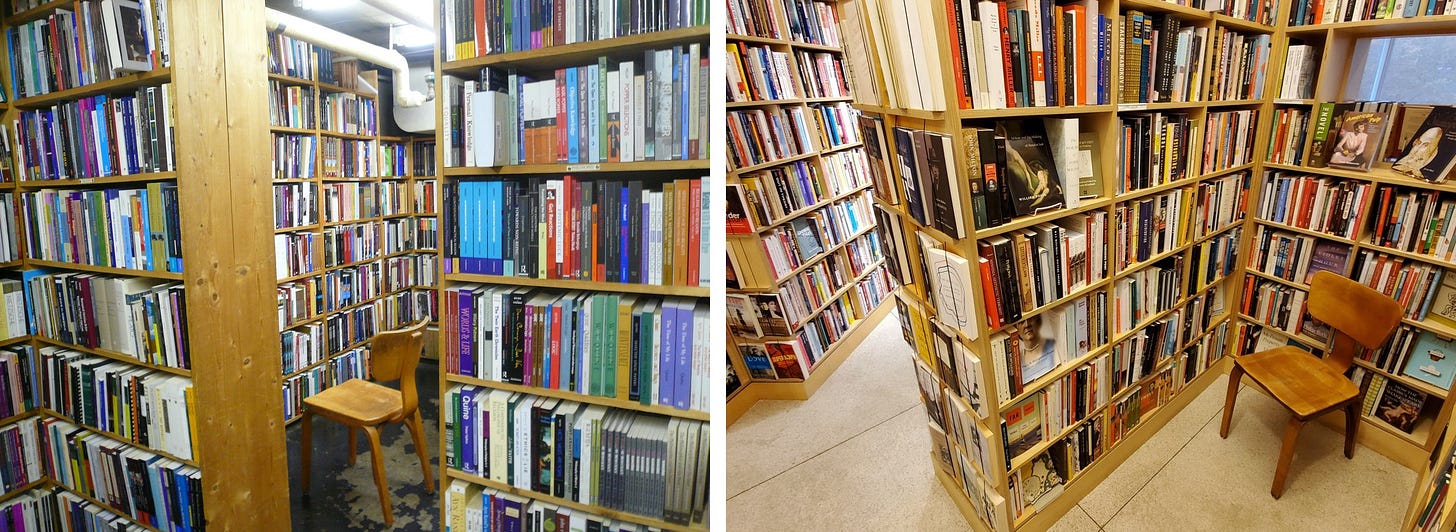

In the stacks at Seminary Co-op, then and now.

Let’s think for a moment about browsing. The word “browse,” it transpires, comes from a fifteenth-century ancestor, brousen, that means to “feed on buds, eat leaves or twigs” from trees or bushes, from Old French broster, “to sprout, bud.” Browsing turns out to be like grazing—moving about oneself searching out nourishing new things—a bit higher up. It takes a while to get the payoff from browsing, it can’t be rushed. You can’t send someone else out to do it for you, or make a map for the effective browsing of your glade or dell. Who knows what might have sprouted yesterday during that warm rain? One thinks of the relationship between ruminate and ruminant.

Book Post’s fall bookseller partner, one I have long been looking forward to, is an almost Brigadoonish physical manifestation of the nature of browsing when it comes to food for the mind. The Seminary Co-op bookstore was founded by actual seminarians in Chicago in 1961. They each put $10 into a collective scheme to reduce their outlay for scholarly books. Driven by the reading interests of its growing membership, the co-operative branched out into a legendary warreny space in the Chicago Theological Seminary’s basement, its layout so convoluted that visitors needed lines on the floor to find their way from dramaturgy to linguistics. It came to be presided over by a gentle, plainspoken fellow named Jack Cella (“I think I was member 1600-something”) who gradually abandoned intended graduate study for running the place and whose “stellar instinct for the books and ideas bound to stir things up,” in the words of one newspaper appreciation, “created a sort of scruffy palace of the mind, a jumbled paradise of print.” The co-op’s fabled front table became a kind of salt lick for the high-powered local intelligentsia.

In 1982 a public-spirited neighbor named Devereux Bowly offered Cella another basement, in a building he owned a few blocks away, for a sibling store that would provide for the neighborhood’s other-than-scholarly reading needs, such as those of children; this basement would become 57th Street Books. Cella lovingly recounts the process for consolidating that store’s low-ceilinged rooms and building its jumble of bookshelves. In his book Author in Chief: The Untold Story of our Presidents and the Books They Wrote, Craig Fehrman describes the nocturnal visits to 57th Street Books by law professor Barack Obama on his way home from the office, spelling his name at the front desk to get his member’s discount for that night’s haul. The yin/yang partnership between Seminary Co-op and 57th Street allowed the Co-op to go all in on books of scholarship and high ambition, leaving the rest of the reading human (the gardener, the cook, the mystery enthusiast) to be catered to down the street and creating an opportunity for the store to have a deliberately community-facing presence in the famously mixed milieu of Chicago’s South Side. Seminary Co-op for its part grew into such an exceptional manifestation of its type that in the nineties professors at Columbia were ordering books from Chicago and trying to poach Cella. (A proper bookstore “becomes part of the general view of the university as a place where people interested in matters of the mind congregate,” said Columbia’s then-provost, referring by omission to that intellectual desert, Manhattan’s Upper West Side. It helps “attract scholars, attract students, retain scholars.” Columbia now has a great bookstore, thank goodness.) Cella told a 2019 panel on bookselling at the Hyde Park Historical Society that after it occurred to him to get an 800 number the store’s mail-order business bloomed and its influence spread. “We spent fair amount of time responding to orders [by phone and email] in a traditional bookstore way, you might like this you might like that,” until an outfit called Amazon starting running ads in the New York Times Book Review promising delivery in what seemed like an impossibly short time. Orders rapidly fell away. Cella remembers the Friday afternoon when one of their two mail-order booksellers, Andrea, asked to go home early because she didn’t have enough to do.

Subscribe to Book Post!

Bite-sized book reviews to your in-box

By Joy Williams, Rosanna Warren, Reginald Dwayne Betts, John Banville, more!

In 2008 the University of Chicago bought the somewhat crumbling if beloved Seminary building and offered to pay to move the Co-op down the street to a custom-designed new space. (Cella promised to use the redesign to fill the predictably erudite customer demand for more books in the sciences and in other languages.) Architect-co-op members Stanley Tigerman and Margaret McCurry designed a beautiful, airy new home purposefully reproducing the meandering, illogical experience of the original, an effect described by poet-member Rosanna Warren as “represent[ing] something about the odd angles of an intellectual life,” and novelist-member Maryse Meijer as indicating “a sense of limitlessness.” Said longtime member and patron, the anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, in what was apparently understood by locals as a compliment: “I must say that the present bookstore is just as confusing as the old one.”

When Cella retired in 2013, the Co-op’s board managed to locate a kindred spirit in former Bay-Area bookseller Jeff Deutsch (who lists ancient philosophy among his reading interests and the forty-year Borough Park chavrusa of his orthodox grandfather among his inspirations). The board felt obliged, though, to disclose that the stores, however widely admired, lost hundreds of thousands of dollars a year. The co-operative model, source of so many of the stores’ strengths—intellectual seriousness, deep roots in its community, the reach of lifetime membership to an engaged diaspora around the country and the world—was hobbling growth and change. The vigor and originality with which Deutsch addressed himself to the problem of finding a durable business model for “a bookstore whose holdings privilege scholarly, literary, beautiful, underrepresented, and enduring books” are attested to in the series of “calls to action” that he issued to the Co-op’s dispersed membership in the years that followed. In order to address the yawning deficit, he called on the stores’ many supporters to “buy one additional book from us this year and then convince a friend, family member or colleague to do the same.” The response was overwhelming. The stores’ sales that month were up 28 percent over the previous year, and they achieved their first year of sales growth in the century. Yet in spite of growth by a third over five years under Deutsch’s watch, above industry standards, the stores continued to operate at a loss. “From a purely profit-driven perspective, we stock books we ‘shouldn’t,’” says Deutsch. “Our tendency to side with culture–embodied in our vast inventory of academic and scholarly publications–makes it difficult to succeed as a business, even as we continue to excel as a cultural institution.”

Deutsch’s bold solution to this conundrum was to recast the two Seminary Co-op bookstores as a nonprofit dedicated to bookselling. “In the twenty-first century, no reader needs a bookstore to buy books and no bookstore can sustain itself financially on the sale of books alone,” Deutsch says. Specifically, Seminary Co-op’s decision to avoid “diluting our space or diverting our attention” with a lot of non-book items to buoy the bottom line, to keep single copies of books they value on the shelves rather than chase profitable “turnover,” and to stock a lot of low-margin scholarly and small-press books are in keeping with its academic clientele, but not the prerogatives of the market. The average bookstore gets 18.3 percent of its sales from things other than books (at Seminary Co-op the figure is 2 percent). Books sometimes only have a few weeks to make their mark on bookstore shelves before they are returned to try out the next batch; the average independent bookstore turns over its inventory twice as often as the Seminary Co-op stores do. “Short-discounted” scholarly and small-press books do not earn their real estate on shelves: Deutsch agreed with bookseller Sarah McNally on The Bibliofile podcast that “you can’t sell them without losing money. The simple act of handling them, opening the box—you’ve lost money.” Replied Deutsch, “I did the math when I started trying to figure out how somehow to stem the tide. The fact is the fewer books we sold, the better we would have done, which is a ridiculous business model.”

How did Seminary Co-op do it? Read on in Part Two of this announcement!

Scenes from a partnership! I’ll be talking the craft with veteran book reviewer Donna Seaman (currently Editor for Adult Books at the American Library Association’s Booklist) as part of Seminary Co-op’s Sixtieth Anniversary celebrations on November 10! Stay tuned for details

Ann Kjellberg is the founding editor of Book Post. She worked as a book review editor at the New York Review of Books from 1988 to 2017, founded the literary magazine Little Star, and is the literary executor of the poet Joseph Brodsky.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe and receive straight-to-you book posts by Ingrid Rowland, John Guare, Emily Bernard, more!

Seminary Co-op and 57th Street Books are Book Post’s Fall 2021 partner bookseller! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their communities. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”