Diary: Anne Waldman, (2) Bard Kinetic

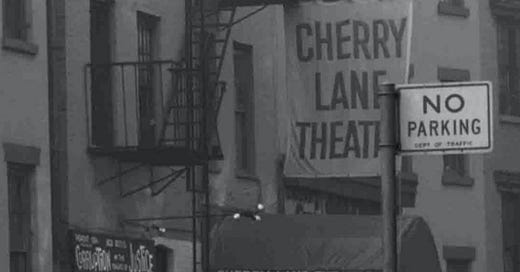

Cherry Lane Theatre, New York, 1963

Read Part One of this post here!

The tiny apartment was cramped. We were always “strapped” (my mother’s term that became a mantra) for cash. I loved listening to the Saturday morning radio shows. And afternoon opera, broadcast live from the Metropolitan Opera House. We ate out once or twice a year in Chinatown. John and Frances both prioritized education and culture.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.