Diary: Carolyn Ferrell, “We must trust in what is difficult” (Part 1)

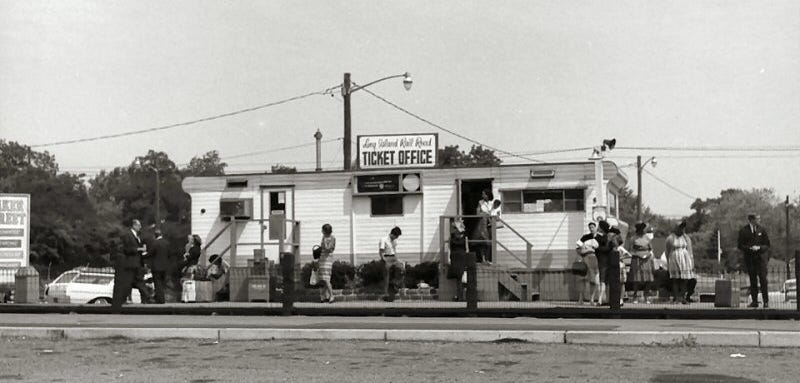

Summer 1968: two six-year-old girls, a hot Long Island afternoon, a wheezing refrigerator, and a suburban kitchen papered in golden burlap and floral trim, beige linoleum peeling at the edges of the floor. Stacy Brown looking at me funny. Because we lived next door to each other in a so-called colored development of tepid Cape Cods, my kitchen looked just like Stacy’s. Except for the shallow bowl of curdled milk on the counter. “You gonna eat that?” she asked. Grimacing, I took a spoonful, and then another. Her eyes never left my mouth.

I made a face, but in fact I loved Dickmilch. If you put enough sugar on top, you could spoon it into your mouth thinking you were eating yogurt (supermarket yogurt was too expensive, my mother explained in the aisles of Hills). For Stacy’s sake I feigned gagging, crossed my eyes, screwed up my nose; this was not the first time I made fun of our odd ways in order to hear North Ronald Drive laugh. There were the obvious flaws: We had no plastic slipcovers, we didn’t play James Brown records on our stereo, we were a family led by a white woman married to a black man living in a black neighborhood and we went around like it was nothing weird. I was forever at the ready with a quip when someone looked at us strangely: “It’s because we’re half German,” I’d explain in an all-knowing way. Half-German meant cultured, it meant excusably weird: That’s how they did things in Europe (a place where rich and famous people went on vacations).

“I wouldn’t eat that if you paid me,” Stacy Brown said after watching me down the last of the Dickmilch. She went home. I envisioned Stacy’s mother, Henrietta, taking the arm of a neighbor and whispering in her ear at the chain-link fence.

Hey Girl, you wanna hear something? Elke Ferrell be giving her kids spoiled milk to eat.

I wanted to run after Stacy and tell her I was on her side; different, yes, and yet just like her. Because, just like her, I used the word ain’t (never within my mother’s earshot—as an immigrant, she prized correct grammar), and, like Stacy, I looked askance at the misdeeds and quirks of white people, who could be mean, unpredictable, and (as my babysitter Cece once explained) prejudiced. They were the worst definition, in other words, of weird. They shouldn’t have to be accepted. I wondered where my own mother fit in this confusion of laws. She was mostly no-nonsense. She hated all prejudice—one reason she left Germany was that the postwar air was filled with the dregs of Nazi sentiment, of what the Germans had “lost.” My mother found that untenable. She despised the way her father nostalgically admired German soldiers, “the best on earth” in his words, while he gambled away their finances and she went hungry. She saw nothing wrong in dating a black G.I. and turned her back on the brother who subsequently pronounced her “dead to him.” As a child I recognized a certain decency, a humanity absent from all the weird and evil white people I knew—whom our block knew—were roaming the earth.

My mother chose to live as a stranger in a strange land; years later, I found myself in similar circumstances. I traveled to Germany after college, to study literature at the Free University in Berlin. The experience was cold, lonely, and also captivating—I found a copy of Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet in a thrift shop in Kreuzberg and read and reread each page religiously. In one letter from 1903, Rilke advises aspiring young poet (and seemingly overall melancholic) Franz Kappus to look to his own experience for inspiration, not turn from it. If Kappus was unable to find his subject there, well, then maybe he wasn’t cut out for the life of a writer. “If your everyday life seems poor,” Rilke writes, “don’t blame it; blame yourself; admit to yourself that you are not enough of a poet to call forth its riches.”

The book became a life raft. I had my official reason for being in an occupied city—I was a student on a grant—but perhaps I was drawn to that unforgiving, cold-hearted place because it was like the town I’d grown up in, my mother’s first refuge from post-war Germany. I had spent a lot of time running on North Ronald Drive—from bullies, from kids who hated my hair and skin, and from my father, who turned his everyday misanthropy on all around him. When my mother made me sardines in tomato sauce on rye bread for lunch, I laughed loudest when the other kids moved to a different table with their hamburgers and fish sticks. My parents didn’t seem to care what the block felt about them, and my mother, overworked with her own four kids and the endless flow of neighborhood toddlers she babysat on afternoons and weekends, often didn’t notice what I was going through.

Laundry, babies, cooking, cleaning, loneliness. Amidst it all, I watched my mother’s strength and bitterness and hope and desolation taking turns in bloom and shadow. During a visit from Hamburg, my mother’s sister didn’t hold back from commenting on how poor our life seemed—she wanted my mother to return to Germany, to a happy life she believed was only possible over there. No, my mother said. Her home was here.

Olive Bean lived two doors down on North Ronald Drive and worked for the New York City Board of Education. She loved my mother. Olive’s daughter, CeCe, would come over after school and babysit me. I idolized her from the start. I knew books were a big deal in their house, as was the large drawing of Angela Davis that sat on an easel in their living room. Once, CeCe brought a copy of Harriet The Spy and placed it in my hands. I felt my heart race when it was over. How astonishing: A girl who actually took notes of her own observations and thoughts and had the gumption to consider herself a writer … [Read Part 2 here!]

Carolyn Ferrell is the author of the book of short stories, Don’t Erase Me. This essay is drawn from her longer memoir, “No Indifferent Place,” which will appear in the anthology, Apple, Tree: Writers on Their Parents, this September.

Book Post is a by-subscription book-review service, bringing short book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to subscribers’ in-boxes, and other tasty items celebrating book life, like this one, to those who have signed up for our free posts and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend! Recent reviews include Sarah Kerr on Carlos Bulosan and Adam Hochschild on unsung heroes of the Nazi resistance. Coming up we have Mona Simpson on Lewis Hyde and Emily Bernard on Imani Perry’s Lorraine Hansberry.

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s current partner bookstore is The Raven in Lawrence, Kansas. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”