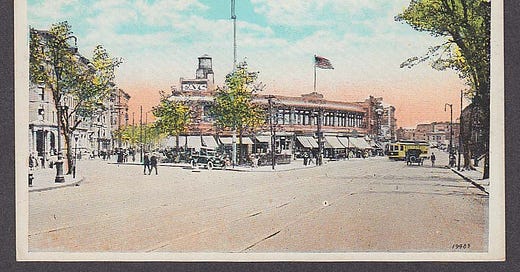

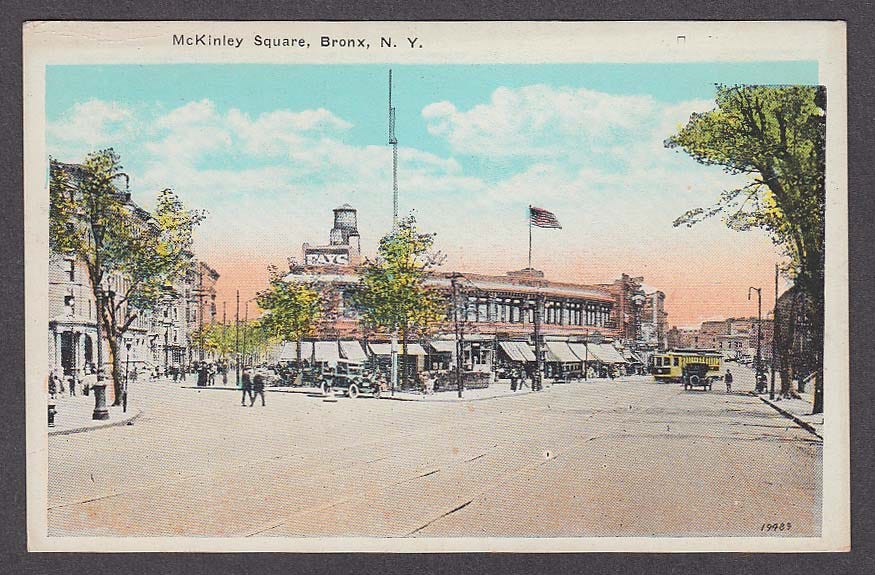

McKinley Square was about ten blocks from the Trotskys’ place at Vyse and 172nd. Postcard from the 1910s

In the early part of the twentieth century, the Bronx's recently-built subway lines and abundance of new apartment buildings made it a popular destination for home-seekers. The front-stoop Bronx of fond memory had just begun when Leon Trotsky, the Bolshevik leader, his wife, Natalia Sedova, and their sons, Lev, who was eleven, and Serge, who was nine, arrived in New York City on January 13, 1917. They came on a Spanish ship; Spain had just deported them. The United States had been their default choice because the only European countries who would accept the dangerous revolutionary were ones that wanted to imprison him. A representative of the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society met the Trotsky family at the pier. They rented a fifth-floor apartment at 1522 Vyse Avenue in the Bronx, just east of Crotona Park and a few blocks from Charlotte Street. The family could not believe how luxurious their place was. When Mr. Trotsky got a call, no small boy had to run from the candy store and yell up the stairs. For a rent of eighteen dollars a month, as he remembered in his autobiography,

that apartment … was equipped with all sorts of conveniences that we Europeans were quite unused to: electric lights, gas cooking-range, bath, telephone, automatic service-elevator, and even a chute for the garbage. These things completely won the boys over to New York. For a time the telephone was their main interest; we had not had this mysterious instrument either in Vienna or Paris.

In Manhattan, Trotsky gave speeches to socialist organizations and immediately fell into disputes with his American fellow leftists, for whom he had contempt. And in the contempt department, no one could out-contempt Trotsky. He described a prominent rival named Hillquit as “a Babbitt of Babbitts … the ideal Socialist leader for successful dentists.” Because of all the work Trotsky did, writing articles for Noviy Mir (“New World”), a socialist paper with offices on St. Mark’s Place, he had no time to take in the city’s attractions. Later he said he regretted that. About two months after he arrived, the February Revolution overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, and orders of exile against people like Trotsky were rescinded. The family made immediate plans to return to Russia. On March 26, fellow Communists gave him a farewell party at a casino in Harlem, where he made an “electrifying” farewell speech, according to Emma Goldman.

Just before the family was about to embark for Russia, their nine-year-old son, Serge, could not be found. Three hours went by with no word of him. Then his mother received a phone call from a police precinct downtown—fortunately, the boy had remembered their phone number. Before leaving the city, Serge had wanted to clear up a question that had been puzzling him. They lived on 164th Street (as Trotsky said in his autobiography, perhaps inaccurately; 1522 Vyse Avenue is at the corner of East 172nd Street). Serge wanted to see if there was a First Street. He set out in search of it, crossed into Manhattan, and lost his way. He went to the police, and they helped him get in touch with his family. The Trotskys made it to their ship on time.

Would they had missed it! Better by far if they had stayed in the new paradise Bronx, in their nice apartment with its affordable rent and modern conveniences. When Trotsky arrived in St. Petersburg (its wartime name was Petrograd), Vladimir I. Lenin had already scored his triumphal return to the Finland Station and had recast the people’s uprising of February as an international proletariat revolution, with his Bolshevik Party—i.e., himself—as its head. But then in July, Lenin overstepped, with an abortive coup attempt against the Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky, and he had to slip secretly back into Finland. While the authorities looked to arrest Lenin, Trotsky carried on, and kept the Bolshevik Party in the middle of the fight. John Reed, the American journalist whose Ten Days That Shook the World is the best account of the Bolshevik putsch, observed Trotsky maneuvering and speechifying during the riotous meetings in which factions by the dozen vied to create a new Russia. Reed described Trotsky, his “thin, pointed face positively Mephistophelian in its expression of malicious irony,” as the Bolshevik firebrand stayed on the attack. In October, Lenin rejoined the front that Trotsky had held for him, and the Bolsheviks hijacked the revolution.

“Mephistophelian,” indeed; it was a dark day for the world when Trotsky and his family left the Bronx. The Bolsheviks’ success would not have been possible without Lenin, and Lenin might not have had a functioning party to return to in October 1917 were it not for Trotsky. A million and a half Russian Jews came to New York; one Russian Jew going in the other direction helped immiserate half the world. What if Trotsky had stayed, and his kids had grown up happily in the paradise Bronx? The family could have become Babe Ruth fans, and Russia avoided seventy-odd years of bloody despotism.

My friend Roger Cohn, who edits the online magazine Yale Environment 360, and whom I’ve known for thirty-five years, told me this story as we were walking in the Bronx neighborhood where his grandparents used to live. He had heard it from his grandfather William “Willie” Cohn, who moved to the Bronx from Manhattan with Roger’s grandmother Sadie, soon after they married. Willie Cohn would go on to be a postal inspector, but as a young man he worked in a restaurant.

“My grandfather was one of the regular waiters, and sometimes Trotsky would come in,” Roger said. “It was well-known that Trotsky did not believe in tipping, because he thought it was disrespectful to the proletariat—he thought that workers should be compensated for their labor and not have to depend on a customer’s mood. Therefore, he never tipped, and as a result the waiters gave him lousy service. To get back at them Trotsky would linger at his table a long time over his tea, so they couldn’t seat another customer. But my grandfather believed that everybody should be treated decently, and he gave Trotsky good service even though he knew he wouldn’t get a tip. To show his appreciation, after my grandfather waited on him Trotsky would not hang around and take up space. When he finished, he would pay his check and leave so they could seat somebody else.”

Trotsky spoke English, although, by his own admission, not well. A search online reveals that the brief time Trotsky lived in the Bronx is recalled mainly in terms of his adamant refusal to tip. In his clumsy English he also urged diners at nearby tables not to tip, either—old Mr. Trotsky, just another New York City nut.

Ian Frazier’s Paradise Bronx, an exploration of Bronx geography, history, and artistic invention from which this post is drawn, will be published next week. You can preorder now from our partner bookstore, Northshire.

Summer Reading with April Bernard this Sunday considers three Brazil poems by Elizabeth Bishop: “Questions of Travel,” “The Armadillo,” and ”Santarém.” Subscribe for free or toggle on in your settings to receive installments, and come on Sunday for conversation in the comments! Join April and editor Ann Kjellberg in virtual conversation on August 29.

We are also in the midst of our August Summer Special, offering a big discount on annual subscriptions and a Book Post mug for the first ten people who order a gift. We are so grateful for your support, which makes Book Post possible.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. Recently in Book Post for subscribers: Adrian Nicole LeBlanc on “Hacks” and female solitude; Anthony Domestico on Rachel Cusk; David Alff on the Port of Los Angeles and the promise and peril of infrastructure.

Northshire Bookstore in Manchester, Vermont, and Saratoga Springs, New York, is Book Post’s Summer 2024 partner bookstore! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. Read our portrait of Northshire here. We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

Vyse Avenue at 172nd Street (East), 1917. Photographic views of New York City, 1870s–1970s, from the collections of the New York Public Library

There are many wonderful pictures of the Bronx in the 1910s at See Old New York.

If you liked this piece, please share and tell us with a “like.”

Love the line, "but one Russian Jew went the other way...". Charming piece on a painful subject.

This was great, thank you. I wonder if by the very end of his life, the thought might briefly have flickered through his own mind: “I should’ve stayed in the Bronx!”