Diary: Jean McGarry, How to write about food

The eighteenth-century food philosopher J.A. Brillat-Savarin tells us in his wide-ranging masterwork The Physiology of Taste that dining is one of the great rewards of being human. First, the bad news: “Man is incontestably, among the sentient creatures who inhabit the globe, the one who endures most pain.” Perhaps, given our increasing sensitivity to non-human sentient creatures, one might dispute this, but let it stand for the moment to savor the next sentence. “Nature from the beginning has condemned him [man, that is] to misery by the nakedness of his skin, by the shape of his feet, and by that instinct for war and destruction which has always accompanied the human species wherever it has gone.” Fair enough. To compensate for the maladies to which the flesh of man is prey, we have the pleasures of the table, which our author develops over time, concluding early on that the art of dining together with other humans must have been the occasion for the birth of language. Why? “Either because meals were a constantly recurring necessity, or because the relaxation which accompanies and follows a feast leads naturally to confidence and loquacity.”

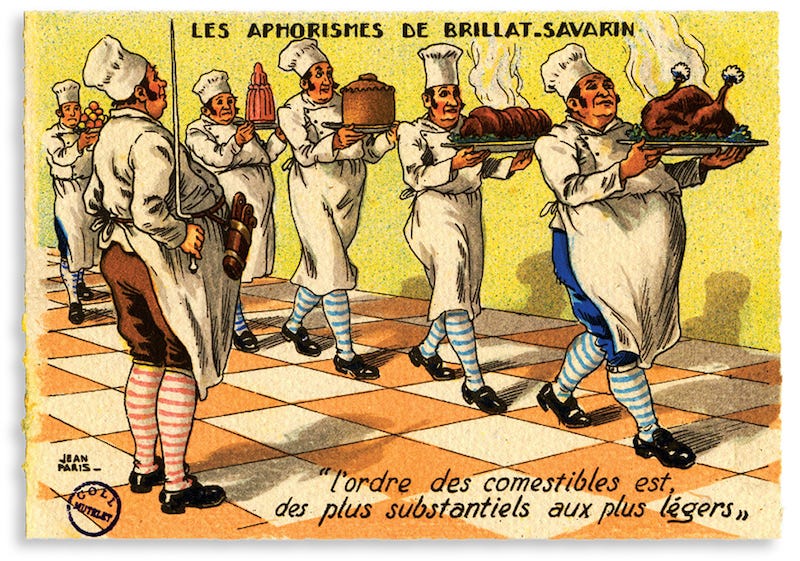

Before discussing the elements of a perfect feast, he distinguishes between the pleasures of eating and the pleasures of the table: “The pleasure of eating is the actual and direct sensation of satisfying a need,” whereas “the pleasures of the table are a reflective sensation which is born from the various circumstances of place, time, things, and people who make up the surroundings of the meal.” Then, he prescribes the ideal: guests to number no more than twelve, the dishes of exquisite quality but limited in number, starting from the most substantial to the least, the time being the evening, the temperature between sixty and sixty-four degrees Fahrenheit, the guests known to each other, and the dining extended to about four hours, with no one going home before 11 p.m., and everyone in bed by midnight.

Our author, at the close of his formula, offers the reader a “bonbon” of the longest meal he ever ate. In fact, he was the host of this meal, or series of meals, offered to his two male cousins. It was meant to be a simple fondue, a dish unknown to the two cousins, but preceded by oysters, skewered kidneys, pastry filled with foie gras; then, the fondue, fresh fruit and sweetmeats, accompanied by sauterne, coffee (a rarity in those days), two kinds of liqueurs. This was at ten in the morning; it was followed by a little rest and a tour of the house and art works, and at two o’clock, the cousins were ready to go home for their bowl of soup. Brillat-Savarin urges them instead to stay for dinner and orders out from nearby restaurants, but also consults his own chef for delicacies. This is followed by a little rest, then tea is served with toast, a punch is made, and suddenly it’s eight in the evening, and the two cousins beg to go home because it’s time for their salad. Ten hours has been devoted to what is considered one meal—the fondue—so it’s not so surprising to read, a little earlier in the essay, the following conclusion regarding the customs of dining in Brillat-Savarin’s time: “We have thus attained to such alimentary refinement that if the pressure of private business did not force us to get up from the table, or if the need for sleep did not arise in us, the length of our meals would be practically limitless.” Just so. The only modern equivalent I can think of that might support the professor’s theory is what incessant dining can be like aboard a cruise ship.

What, then, makes an ideal food writer, the kind we’re willing to read two-hundred-plus years later, when we’re no longer eating railbirds or whole turkeys at a sitting. Brillat-Savarin gives us a clue in an essay he placed at the end of his book, under a section headed “Varieties,” which I think he intends as a miscellany. The essay is entitled, “Traveler’s Luck,” and, in it, we can see this writer’s tricks of the trade. As the story of this rather critical episode of the professor’s life opens, he is on his way to find out whether he lives or dies. As a royalist, and thus a traitor to the revolution, he has been hunted out of Paris and dispatched to the provinces, to a Citizen Prot, who will decide whether he’s cleared for exile, or doomed to the guillotine. En route, he stops at an inn, smells some wonderful game being roasted in the fireplace, gets himself invited to share a meal with a group of lawyers, has a gay old time, then mounts his steed, named Joy, and heads off to the moment of decision. At the Prots’, he manages to entice the wife of the household into a discussion of music, which is her passion. They talk about music and composers—every piece and every man is known personally by the accused traitor. He proves a delight to this poor woman, starved for company. They talk, they sing, they play. By evening’s end, she whispers in his ear that his life and his destiny are assured, and off he goes.

If we look closely at the self-presentation in this riveting anecdote, we see not only the real character of the writer, but the highly pleasing persona he projects to his reader. Every part of this persona is vital to his success as a food writer. What are these qualities and where do we see them in this account? Well, let’s start with the opening. “One time, mounted on my good mare, la Joie,” our author begins, “I rode over the pleasant slopes of the Jura.”

This might almost seem like a ho-hum opening, until we read a little further on, and find out what our writer is facing at the end of the line, beyond the pleasant slopes of the Jura. What reminds us of other food writers like Julia Child, James Beard, possibly more remotely M.F.K. Fisher, is an appetite for life—even for a ride on his steed, Joy, over the pleasant slopes; to enjoy the moment, even facing what he’s facing. A certain appetite for life, and an undying optimism; an eagerness to be pleased; and lastly, an ability, shared by Fisher, to set aside pain and fear. I love the command on computers to refresh; I’m not sure what it means, but these people, who write about food, have that ability to refresh themselves. We can compare the quiet joy Brillat-Savarin feels about his momentous journey to Fisher’s essay “Sea Change,” where the disaster of the Great Depression, several marriages gone, and the occasional poverty that inspired her book “How to Cook a Wolf,” are met with energy, grace, and optimism. The best face is put forward to meet the world. This is one of the features that appeals in food writing, that draws readers to imagine feasts and the preparations that go into them with an eye toward pleasure, and not on work, boredom, difficulty. It’s almost a childlike quality, certainly one that Julia Child invariably displayed in her TV show, when the chicken falls on the floor, or she burns her hand.

One imagines, further, that the food writer learns to cultivate this joie de vivre, if it doesn’t come regularly, or naturally. The act of writing itself—in character, that is, in the persona a reader expects from the writer—dispels the clouds and brings on the appetite, the optimism, the eagerness to be pleased, the capacity to set aside pain and fear (or, in Fisher’s case, to write interestingly about it).

Next, a storyteller has to produce a moment, or more than one, of adversity; otherwise, there’s no interest in reading on. Sometimes we call this suspense, but it’s really tension, dramatic tension, and not just about the outcome, sometimes simply a curiosity about what the author is doing with the materials at hand. In James Joyce’s story “The Dead,” up to the point where the main character and his wife leave a meticulously described dinner party in the wee hours of the morning, we have no idea what the story is about, but we feel a gathering energy, tension. We wonder why it’s taken so long to arrive at the target. We already feel connected to the main character, Gabriel, because we’ve been in his head for the whole night. What will happen to him? Will his gathering passion bring about something satisfying, or is he in for a shock?

A good essay on food probably needs to have something of this tension in it, and we encounter it at the moment in “Traveler’s Luck” where the beleaguered royalist finds that, instead of the luscious birds being roasted on the spit, he’s slated to dine on mutton and bouillon, which he hates. The menu proposed by the innkeepers, he said, “was made especially to depress me, and once more all my miseries closed in upon me.”

Thus commences a suspenseful interval where the conspiring innkeeper and guileful guest work out a way for our author to partake of the lawyers’ feast. First, he has to ask, he has to venture forward. And he does. “Sir,” he says to the innkeeper, “do me the kindness to say to these gentleman that an agreeable table companion asks, as a great favor, to be admitted to dinner with them,” adding, “that he would assume his share of the expenses, and that above all he will be deeply indebted to them.”

The gambit works and Brillat-Savarin, en route to die or be exiled, dines with the lawyers, who don’t charge him; nor, out of politeness, does he ever tell them why he has to leave the table so early and fly away on his steed.

The last traits we see in “Traveler’s Luck” that might serve the food writer are found in the visit to the Prot household, and the way in which the author’s musical talents and knowledge win over the lady of the house and win the author his life. Implied in his description of the evening spent at the Prots is a great trustfulness and sweetness that allows Brillat-Savarin to write of his judge, “It is true that I found Representative Prot strongly prejudiced against me: he stared at me with a sinister air, and I was convinced he was about to have me arrested …” In the next paragraph, he adds, “I am not one of those people whom fright turns vengeful, and I truly believe that this was not a bad man; but he had limited capacity for his position and did not know what to do with the enormous power which had been entrusted to him.” Our author then describes the evening of music spent with Mme. Prot, and his stance remains warm and generous to those he might considered his enemies.

Is Brillat-Savarin a better or more interesting writer because of this relentless sweetness and grace? “Traveler’s Luck” is a bit puzzling, perhaps to twentieth-century eyes. Why wasn’t he scared, angry, and resentful?, the modern reader asks. Why is the darkest moment—or the next to darkest—the moment when he thinks he’s going to have to eat mutton instead of quail?

I think therein lies another necessary trait of the food writer. Food has to be important; it can’t be lost in travail, either of cooking or eating, or conversing at the table. Luke Barr, nephew of food writer M.F.K. Fisher, tells a rather dark story about how Fisher, after leaving a festive gathering of chefs in the South of France, puts herself through an ordeal, living alone in hotels in forbidding French provincial towns through the Christmas holiday, a time when all other humans are occupied with family, most hotels are empty, and even most restaurants and cafes are closed. M.F.K. is trying to think about a new life on her own in California, leaving behind her beloved France, where she would go to get on with her writing. Her writing about food, though rich in personal detail, leaves out the long periods of struggle in her life, but Barr has access to it in Fisher’s journal, kept during those winter months in 1970. Here she is coping with a rather harsh French town that wants to close in on itself and is not welcoming to strangers. “I could live well,” she says

and perhaps more sensibly than I do now, on a piece of fruit from one pocket and a handful of nuts and raisins from the other. But where would I go to eat them? The park benches are deserted even by the birds, this time of year. My hands in mittens would drop every raisin. What is more, I—not a different person but I—would grow more and more away from the human race, further into my own tumbled, troubled ponderings. No, it would be unwise—for me, that is. I am determined to stay on the human side, perforce.

Barr quotes another passage from the diary:

Always before, in France, I have fought a hard battle within, to return to America happily, I have wanted to stay here. But by now I have decided to end my life in California, as far as one can decide such things. My two children are American … and I have decided to stay as near them as they wish to be, instead of establishing myself in southern France as I once dreamed of.

Fisher’s experiment in holing up in a hotel, first in Arles, and then Avignon, at Christmastime tells us something about her venturesome personality, her wish to put herself to the test to see what will happen. But it reveals the other side of a writer’s life, which is spent in solitude, toiling away to make something that will appeal to readers; and, in her case, be something valuable as literature.

How is food made into an art? is the question, I guess. We know the answer the five-star chefs would tell us. Labor, meticulousness, long hours, and total dedication. Not so different from a writer’s life. For the epicure or wine connoisseur—reading, thinking, tasting, traveling, talking to others, being both scientific and instinctive. Learning to train the palate.

For the food writer, there’s a second step, and that is finding the words to convey the delicate sensations of taste. To me, that seems almost a poet’s task, to find words for things that haven’t been described, can’t be described, or have never been described accurately. Feelings, tastes, sensations, thoughts, divinations, intuitions. I would imagine to be a good food writer, you’d have to be—not only a graceful and generous person as Brillat-Savarin so clearly was—but a highly discerning one, with an inborn palate of words very much like what a natural musician has in his hands and his ears, and then the desire to cultivate that talent. The words have to be as exquisite as the tastes on the tongue, and as evocative. In addition, an ability to turn an eating experience into a narrative, an ability to use the self as a interesting subject, and lastly, a great appetite for life, which gleams through the language.

Jean McGarry is the author of nine books of fiction, most recently the short-story collection No Harm Done and the novel Ocean State.

Book Post is a by-subscription book-review service, bringing to your in-box book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers, plus a few other treats, such as this one, for followers of our free updates and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend! Recent reviews include Joy Williams on David Wallace-Wells and Àlvaro Enrigue on Roberto Bolaño. Coming up we have Geoffrey O’Brien on Marvin Gaye and Hugh Eakin on Alfred Steiglitz. Visit our archive for more.

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s winter partner bookstore is Greenlight. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram.

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”