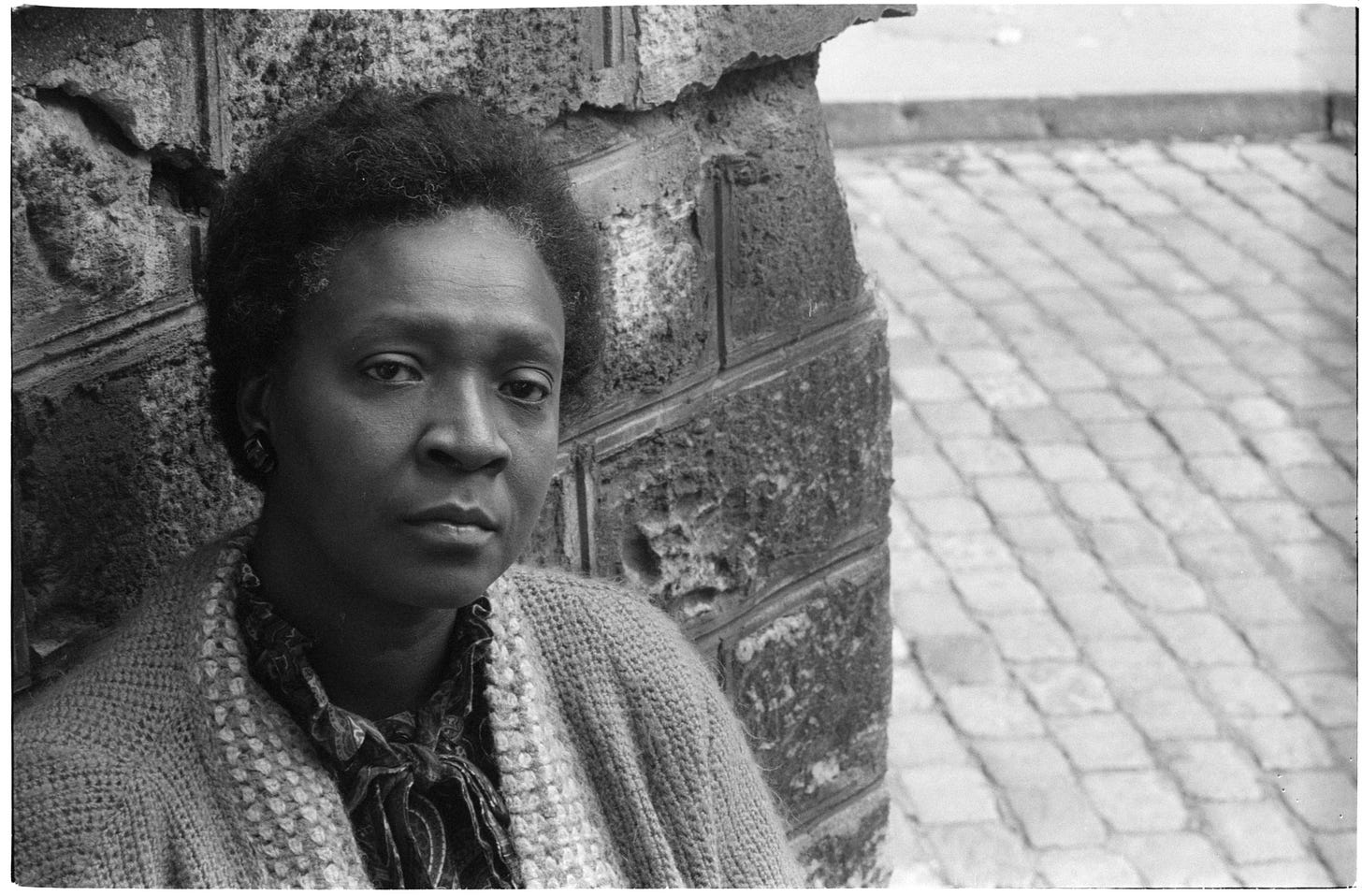

Maryse Condé, 1981

(1980) Since the political situation in Guinea had seriously deteriorated, Mamadou Condé, my first husband, had to flee and take refuge in the Ivory Coast. It was from there that the children, one after another, came to join me in Paris. Denis first, landing at the airport dressed in a pale-green boubou of bazin fabric in the depth of winter’s cold. Then the three girls, shortly afterwards. They brought me great happiness but also the prospect of a heavy financial responsibility. Richard, who would become my second husband, earned a good living as translator with Kodak-Pathé. But what was enough for a couple was not good enough to feed so many mouths. We had to abandon our studio on the rue de l’Université which we both liked so much and move to a vast but nondescript rental in Puteaux. In order to confront my new role as a suburban mother of a large family, I could no longer be content with working part-time at Présence Africaine nor teaching classes for practically nothing as I had done with Robert Jaulin, my friend in the University of Paris Ethnology Department, and was now doing for Claude Abastado at Nanterre and Jeanne-Lydie Goré at Paris III-Sorbonne, intellectuals who had taken an interest in my career. I needed a permanent job with a regular salary. It is difficult to imagine that in those providential times there was virtually no unemployment. I had no trouble finding a job with a new African magazine. It was neither left-wing nor militant, center-left at the most. I never knew exactly where its funds came from. Its director was a native of the Comoro Islands, a bit of a crook, quite handsome, his hair parted to one side, and very knowledgeable about the situation in what was then called the Third World.

I was somewhat disappointed because he put me in charge of the literary column instead of the political page. From early morning, the luxurious offices of the magazine were invaded by a crowd of visitors, supplicants, and commentators of recent political events in Africa. I discovered that Guinea was not the only dictatorship. Paris harbored a bunch of opponents to the current regimes, as well as those sentenced to voluntary exile who had fled to safeguard their freedom and even their lives. The peremptory nature of their comments and their categorical and cursory analyses made me laugh since they appeared to be totally divorced from their countries with no power whatsoever over their fates. I was far from imagining that several of them would become presidents of the republics they were criticizing. At noon, we crowded into the restaurants and lunched briefly on andouillette sausages and French fries.

I liked my job of reviewing books I thought important, writing authors’ portraits and doing interviews wherever possible. That was how I met Mariama Ba. She had just published her book So Long a Letter (an African bestseller), and checked into a hotel in the Latin Quarter for its promotion. We had breakfast in a cafe. All around us the boulevard Saint-Michel was a hive of activity: students running to the Sorbonne, professors walking serenely, their briefcases under their arms. I envied this academic frenzy, since my student years had not been the best of times.

A mutual sympathy drew Mariama Ba and me closer. As writers we were very different yet we shared the same fear of others and suffered from the same feeling of insecurity.

“If they hadn’t forced me,” she said, “I would never have had the courage to publish my book. It would have stayed in a drawer.”

“That would have been a pity!” I exclaimed, because I loved her book.

At the magazine, I did everything I could to win over my editor-in-chief who was very reluctant. “It’s an old woman’s story,” he said, shrugging. “What would people say if we made such a fuss about it?”

An old woman’s story! He hadn’t understood a thing. He hadn’t appreciated this early cry for the liberation of African women and the elimination of traditions that were stifling them. Mariama Ba and I promised to meet again after she had finished her tour around Europe.

“Come and see me in Senegal,” she pleaded. “We have so much in common.”

I was stupefied when the news came of her death a few months later. In the years to follow, in homage to this modest and astute woman, So Long a Letter has always been on my course list.

Book Post supports books & readers, writers & ideas

across a fractured media landscape

Subscribe to be a part of our work

Unknowingly, I began to acquire a reputation for virulence for I had the audacity to write what I thought about the novels and essays I was in charge of reading. My editor-in-chief did not appreciate this frankness. “Water down your wine,” he advised me. “Turn your pen seven times in your inkwell. People will end up thinking you’re jealous and frustrated.”

During this time I wrote A Season in Rihata, my second book, published by Robert Laffont where a fellow Antillean was the director of a collection. Since this second novel proved to be no more successful than the first, people might have thought that I was taking my revenge wherever I could. My compulsive desire to work, however, did not die down. I dashed from one end of Paris to the other, jumping onto buses and scrambling down the steps of the Métro despite the heavy Nagra tape recorder hanging from one shoulder. Twice I went to Belgium and once to Sweden, which left me with unpleasant memories since the conference on feminine literature to which I was invited turned out to be a nest of militant lesbians who treated me with the utmost contempt. Nevertheless, I had never experienced such a feeling of freedom. I was not entirely reconciled with Paris. Too-bitter memories floated around certain districts. But the city didn’t scare me as it once had. Deep down, I was convinced I would continue my life elsewhere. My existence would be turned drastically upside down. I would go and live in another country and do things besides hatching cultural articles for a second-rate magazine. I would discover the world and maintain original and enriching relationships.

I would eventually return to settle in Guadeloupe, after the publication of my novel Segu in 1984. I bought an old “change-of-air house,” as we called them, in Montebello, in the region of petit bourg where I had spent my holidays as a child. The area around petit bourg has a subtle, somewhat old-fashioned charm which speaks directly to my heart. In Montebello, I often invited my close circle of friends for a meal. I had learnt my lesson. Just as my cooking was not genuine Guadeloupean, I too would never be a genuine Guadeloupean. But what does the word “genuine” mean? Nobody has been able to explain it to me. In this age, where everything is interconnected and exchanged, is it possible or even desirable?

Since I had returned to Guadeloupe, declaring somewhat pompously that I was putting myself at the service of my island, nobody apparently needed my services. I was never invited to participate in something worthwhile and spent all my time on my balcony, writing works which nobody was interested in. When they passed by our front gate, my neighbors would peer up to take a look at “the African”—as they called me since it was rumored I was from Mali—busy with her futile scribbling. You could count the number of our visitors on your fingers. There was my brother and sister-in-law with one or several of their children who came to visit from Basse-Terre. We had nothing to say to each other; they didn’t like my cooking but felt obliged to come by and be bored once a month. Our friend José, a militant for independence, came whenever the fancy took him in order to sell the party’s newspaper. But finally, I had absolutely no desire to leave Guadeloupe. By Guadeloupe I mean an entity I have trouble defining, such as the nature of the island—the sea, the beaches, the forests, banana groves and sugar-cane fields—not because of its beauty, spoilt year after year by the property developers, but because of a concert of subtle, faint voices it emitted for me alone. This concert irrigated my imagination and illuminated my thoughts.

Translated by Richard Philcox

Read Geoffrey O’Brien for Book Post on the bookstores of Paris.

Maryse Condé is the author of the novels Segu, I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem, The Story of the Cannibal Woman, Victoire: My Mother's Mother, and Heremakhonon, among other books. She was the recipient of the 2021 Prix Mondial Cino-del-Duca. She received the one-time-only New Academy Prize, an honor that filled in for the scandal-plagued Nobel Prize during its suspension in 2018, the selection process for which included nominations from librarians and a public vote. She was born in Guadeloupe in 1937. This post is adapted from her recent memoir Of Morsels and Marvels, translated by Richard Philcox, published by Seagull Books.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture. Or sign up for our free posts, like this one, about the world of books. Previous posts include Rosanna Warren on Edmund de Waal’s Letters to Commodo, Hugh Eakin on the friendship of Picasso and Apollinaire, Geoffrey O’Brien on Raymond Queneau, Jamaica Kincaid on gardening and empire.

Print: A Bookstore is Book Post’s Summer 2021 partner bookstore! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

I loved this excerpt. Good for her, and for returning to the island of her birth. Thanks again.