Diary: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, (1) The Politics of Translation

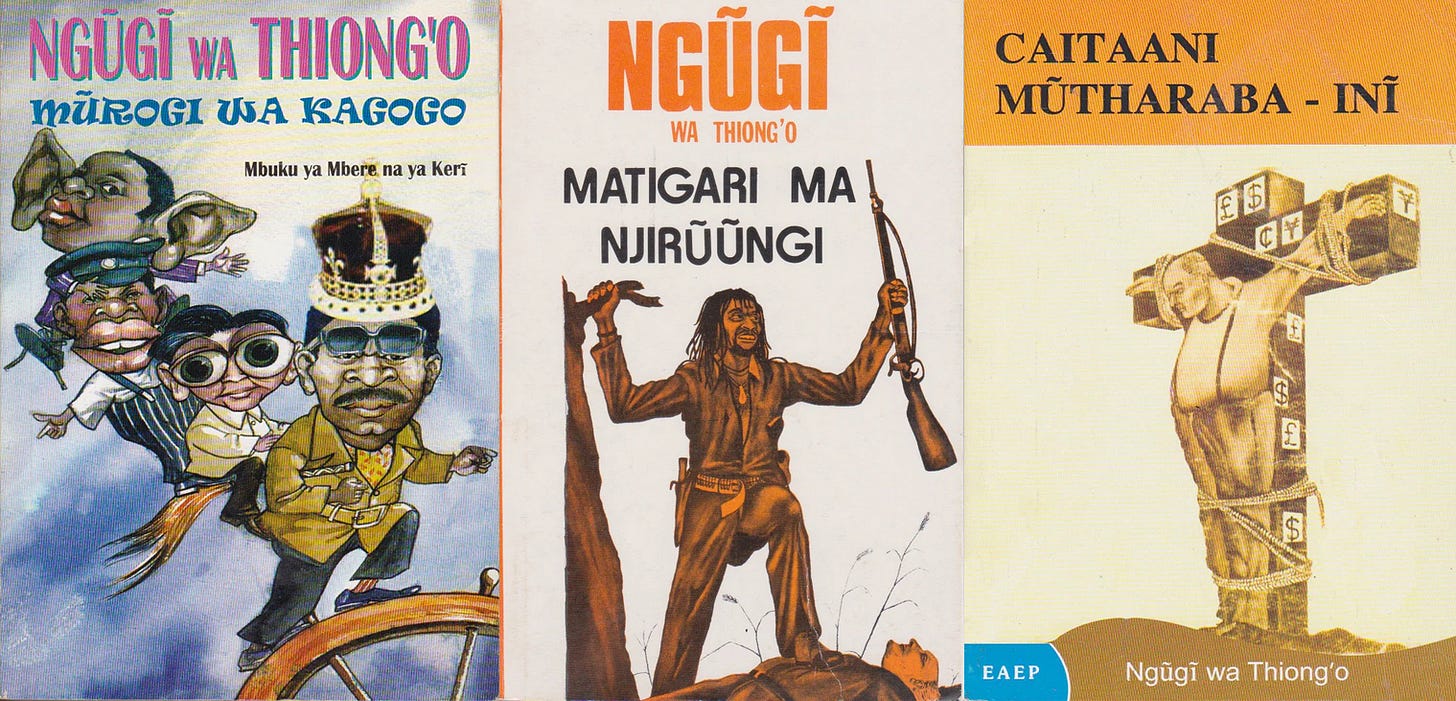

Works by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o in Gĩkũyũ

In the history of conquest, the first thing the victorious conqueror does is attack people’s names and languages. The idea is to deny them the authority of naming the self and the world, to delegitimize the history and the knowledge they already possess, delegitimize their own language as a credible source of knowledge and definition of the world, so that the conqueror’s language can become the source of the very definition of being. This was true with the English conquest of Ireland, Wales, Scotland; or the Japanese conquest of South Korea; or the USA’s takeover of Hawaii: ban or weaken the languages of the conquered, then impose by gun, guise, or guile their own language and accord it all the authority of naming the world. A Captain Pratt summed it up best when in 1892 he set up residency schools for the education of Native Americans, bragging that the aim was to “kill the Indian … and save the man.” It was done with the enslaved. African languages and names were banned on the plantations; and later on the continent as a whole—so much so that that African people now accept europhony to define their countries and who they are: francophone, anglophone, or lusophone.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Book Post to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.