Diary: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, (2) The Politics of Translation

The Bible in Gĩkũyũ

Read Part One of this post here!

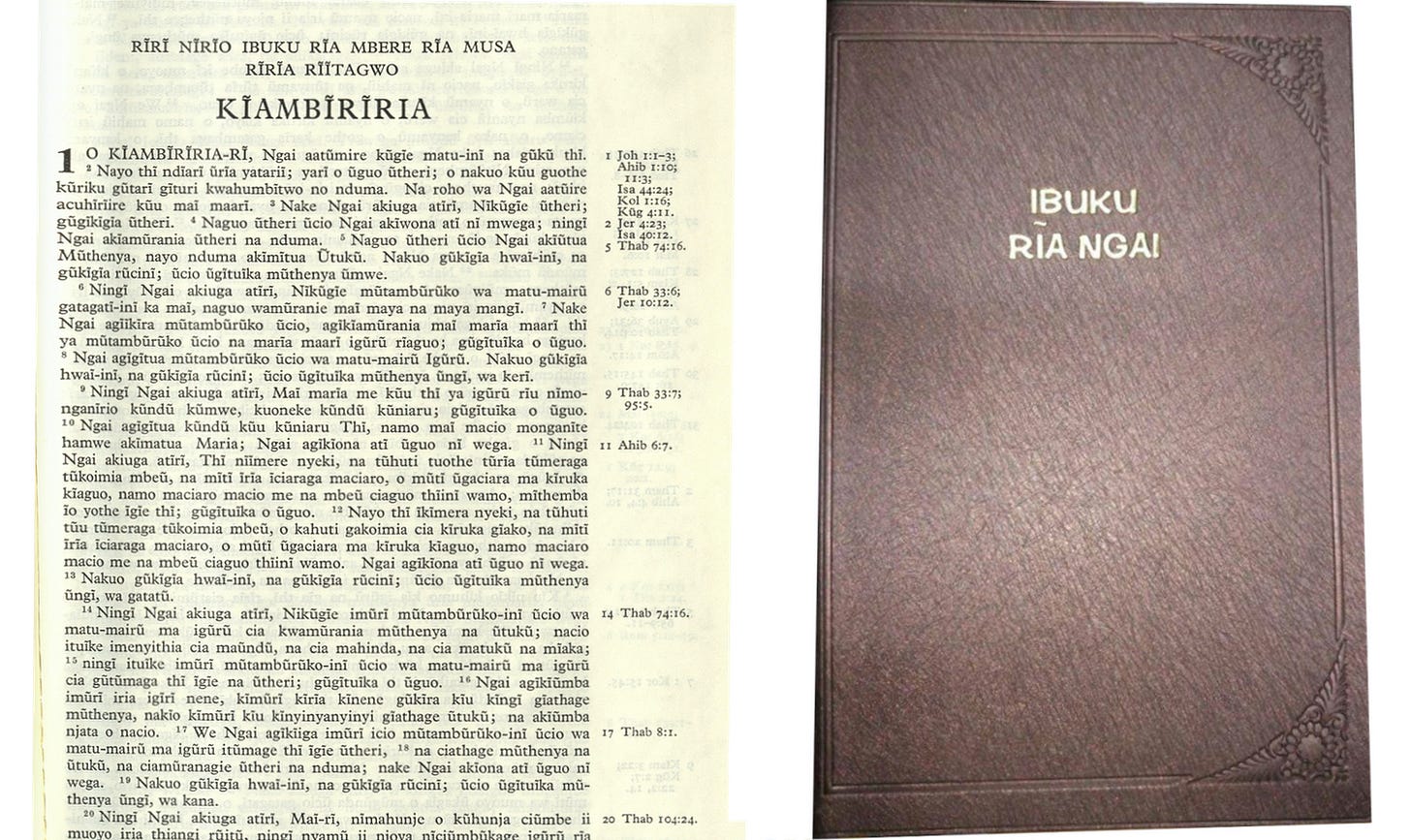

Translation—a kind of dialogue or conversation among languages—is another challenge to the orthodoxy of monolingualism. Translation is one of the means by which languages and cultures do and can give life to each other. Translations can be seen as conversation; a conversation, as opposed to commands or exhortations, assumes equality among interlocutors. The Bible in Gĩkũyũ, another part of my culture, was a translation of a series of translations, English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic all the way back to whatever language that God, Adam, and Eve used in the Garden of Eden. I was very impressed by the fact that Jesus and all the characters in the New and Old Testament spoke Gĩkũyũ! Even God, in the Garden of Eden, spoke Gĩkũyũ!

This inheritance from translation is not unique to Gĩkũyũ or to Africa. The Bible in translation has similarly had an impact on the growth of many languages in the world. The translation of the Greek and Latin classics into English, French, and German not only aided in the growth of the languages but the same classics, in their translation, have made an impact on the study and development of drama, poetry, and philosophy in general. It is impossible to imagine Shakespeare without translations. He worked within a culture where translations from other languages into the emerging national tongues were the literary equivalent of piracy for silver and gold on the high seas.

Support our work with your subscription

For African languages to occupy their rightful place in Africa and the world, there have to be positive government policies with the political will and financial muscle behind them to support languages in all their multiplicity and mutuality. Publishers and writers too. A meaningful and practical policy has to start with the assumption that every language has a right to be, and each community has a right to their own language, or the language of their culture. That means equitable resources for their development as means of knowledge and culture.

This can help in the complex give-and-take among languages and cultures. Cultures of humans should reflect that of nature, where variety and difference are a source of richness in color and nutritional value. Nature thrives on cross-fertilization and the general circle of life. So does human culture, and it is not an accident that cultures of innovation throve at the crossroads of travel and exchange.

Aimé Césaire once said that cultural contact was the oxygen of civilization. Translation, the universal language of languages, can really help in that generation of oxygen. Translation is an integral part of the everyday in nature and society and has been central to all cultures; but we may not always notice it. In more equitable relations of wealth, power, and values, translation can play a crucial and ultimate role in enabling mutuality of being and becoming even within a great plurality.

This post is adapted from “The Politics of Translation” in Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s The Language of Languages: Reflections on Translation, published this month by Seagull Books. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is the author of many novels, short stories, essays, a memoir, and several plays. His novels include The Devil on the Cross, The River Between, Petals of Blood, and Weep Not Child. In The Language of Languages he writes, “in 1977, after publishing four novels in English, I decided to write directly in Gĩkũyũ. But I found it necessary to do a translation into English, for, even within Kenya, only one community speaks Gĩkũyũ. We are a multilingual nation. The problem would have been solved immediately if all the other African languages were equally thriving in publishing. Then it would have meant that the book would be available in all the forty languages. But that was not the reality. I translated my first novel in Gĩkũyũ, Caitani Mũtharabainĩ, into English as Devil on the Cross … Matigari, my second novel in Gĩkũyũ, was translated by Wangui wa Goro into English. Her translation is concerned less with making the reader conscious of the source language than in making it flow in the target language while capturing the spirit of the novel. I translated my third novel in Gĩkũyũ, Mũrogi wa Kagogo, as Wizard of the Crow. Here I followed Goro’s footsteps: I was more concerned with its flow in the target language. I argued that if anybody wanted to know how it felt in Gĩkũyũ, then they should read it in Gĩkũyũ … My difficulties in writing in Gĩkũyũ have not really come from the act of writing or the process of translating but, rather, from the publishers. I have about five to six manuscripts in Gĩkũyũ that have not yet found the light of publication. When the publisher accepts to publish in Gĩkũyũ, it is only with an eye to the English translation, to which they will then give all the attention. So ironically, translation into English, be it auto-translation or by another hand, has worked against my efforts in Gĩkũyũ. I now want to make sure that my next major works in Gĩkũyũ are not translated into English until a specified period of time, say two or three years.”

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world.

Become a paying subscriber—or give Book Post as a gift!—to support our work and receive straight-to-you book posts by distinguished and engaging writers. Among our posters: John Banville, Mona Simpson, Emily Bernard, Adrian Nicole LeBlanc.

The book discovery app Tertulia is Book Post’s Winter 2022 partner bookseller. Book Post subscribers are eligible for a free three-month membership in Tertulia, sign up here.

We partner with booksellers to link to their books and support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens across the land. Book Post receives a small commission when you buy a book from Tertulia through one of our posts.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”