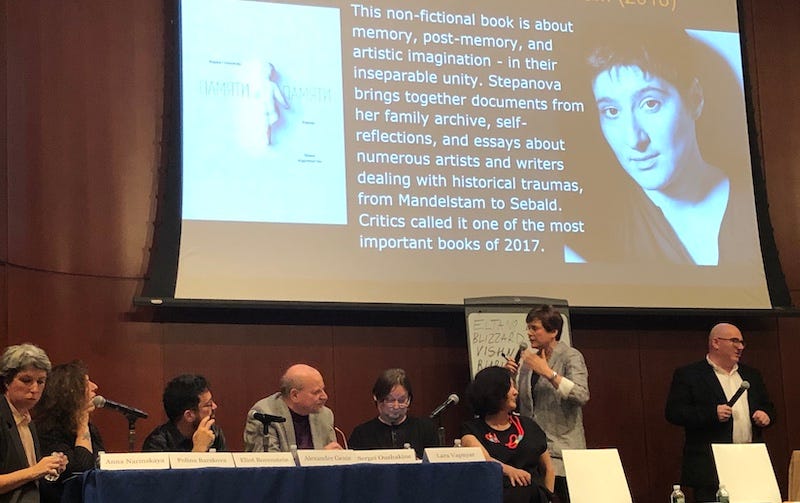

Super-NOS prize contenders have at it in New York: Moscow critic Anna Narinskaya; poet Polina Barskova; scholar Eliot Borenstein; critic and radio journalist Alexander Genis; scholar Sergei Oushakine; novelist Lara Vapnyar; NOS Prize founder Irina Prokhorova; and moderator Mark Lipovetsky. Pictured: Previous NOS winner Maria Stepanova

If you read no further than the first sentence of this post: please order your books online from this new site, Bookshop, instead of Amazon.

Bookshop is the creation of prodigious inventor of digital reading opportunities Andy Hunter. Hunter first appeared on the scene in 2009 when he announced the creation of Electric Literature, a multiplatform digital purveyor of short stories that (at the time) directed the costs of print publication to the writer. Electric Literature has evolved a lot since then, but it’s still a widely followed and lively source for new writing. With energy to spare, apparently, Hunter went on to found, with Grove publisher and legendary brat-pack editor Morgan Entrekin, the book-culture site Literary Hub, initially as a vehicle for publishers to roll out their wares in a convivial (as opposed to promotional) spirit. (LitHub now also has sub-sites devoted to book reviews and crime writing.) And then he founded, with Koch-family black-sheep literary sibling Elizabeth, the publishing house Catapult, which also functions as a virtual and real writers’ community.

Hunter always seems to be looking for ways to train the anarchic forces of the internet on nourishing literary value. His new effort, Bookshop, is probably the most public-spirited of them all. His work as a magazine and book publisher made him acutely aware of the threat Amazon’s growing bookselling monopoly posed to the health of writing (a subject we’ve covered here and there). The American Booksellers Association had created an alternative, IndieBound, to drive online sales to bookstores, but IndieBound had not found the right technical formula to match convenience for the reader with support for the bookseller. Hunter set about developing Bookshop, in collaboration with independent booksellers, to offer a more robust alternative in several respects. Bookshop offers a “seamless” (as they say) shopping experience to the book buyer; it distributes revenues to independent booksellers; and, importantly, it offers those who link to it online a share in sales that is more generous than Amazon’s. (You may not know that when you buy something by clicking through a link to Amazon, the outlet offering you that link gets a cut.) Currently these so-called “affiliate links” are a major source of revenue for online media outlets, a growing share of their bottom line as advertising and subscriber dollars shrink. Until now Amazon has managed to corner the “affiliate links” market. But Bookshop allows not only magazines and newspapers, but independent bloggers and writers and Instagram “influencers” and anyone really to get a 10 percent share from the sale of a book they link to online (Amazon offers 4.5 percent), more for Bookshop’s partner bookstores. (Book Post still links to independent booksellers directly, giving them a larger share of sales. We do not collect affiliate revenue.)

The one competitive advantage that Amazon retains over Bookshop is its steep discounts. This is a feature not a bug. Amazon’s discounts are designed as a loss-leader to amass customers and drive its competition out of business, and Bookshop exists to serve independent booksellers (and, with them, publishers and writers). Not only does Bookshop decline to undercut the prices of independent booksellers, it actively promotes them, by sending its customers information about their local shops and participating in various joint marketing ventures. It sees itself as an enabler rather than a competitor for bricks-and-mortar retail.

So this is a great thing, and I implore you, readers, to order from Bookshop whenever you are not buying from an independent bookstore directly and to link to it when you refer to a book online.

Support our work and become a paying subscriber to Book Post

See what you’ll be getting here

Help spread the news of books and ideas

We found ourselves entangled in another ingenious literary invention this week: an American outpost for Russia’s Super-NOS prose competition. The NOS Prize (an acronym for “new prose” in Russian, and also a reference to Gogol’s story about the appendage) was founded in 2009 as an original kind of literary prize, one in which the internal mechanism of the choice would be entirely visible and, indeed, participatory. A panel of jurors (prominent writers and critics) present and argue for their choice of best book from a roster they assembled ahead of time (in another layer of transparency, past jurors have published their disputatious correspondence compiling the list). They are interrogated by a panel of “experts” (in this case, graduate students in Russian literature), and they arrive at an anointee that includes votes from the jury, the experts, and the audience.

The NOS prize is awarded every year in various places, and this year the remote panel in New York selected from ten years of NOS winners to arrive at a “Super-NOS” for the decade, and what a decade it was. NOS prize founder, the publisher and philanthropist Irina Prokhorova, described the rationale for the prize: In Soviet times judgments about what to read were political and unchallenged. After the fall of the Soviet Union, Prokhorova felt, the country needed “new instruments for evaluating literature”; she indicated that open debate in Russian society is still not exactly thriving. She created the NOS prize as an ongoing vehicle for real-life discussion of what it means to have literary merit. For example, the jurors and experts wrestled with the question of whether the decade’s winner should be the book that was the highest literary achievement or one that was the most representative of the moment, or that brought something new into literary language. Prokhorova observed that today’s Russia is “not a pleasant place, not a cozy place,” and needs a new literature to capture this reality. In the end, the book that carried the day, Vladimir Sorokin’s The Blizzard, which has been translated into English by Jamey Gambrell, was almost provocatively grounded in the Russian classics and crafted in a timeless amalgam of styles. The book was just too much of a masterpiece, it seemed, not to win. There was some remorse about this. Some jurors noted how many great books weren’t on the list at all, such as those of Nobel-prize-winner Svetlana Alexievich and novelist Victor Pelevin. But a juror remarked to general assent that Sorokin has described himself as an Orwell for contemporary Russia, and we all need our Orwells. (One interesting feature of the NOS prize is that it covers fiction and nonfiction. The runner-up to The Blizzard was Maria Stepanova’s internationally celebrated reflection on memory and the past, which will be published next year in the US by New Directions.)

After the contest Prokhorova asked some of us if we thought there was space for such an institution in the US. I quipped that we don’t seem to have any shortage of argument, but when I think of some of the controversies now roiling the literary world it did seem like it would be welcome to have some setting in which people of divergent views sit down, face to face, and try to change one another’s minds, and those of their audience, rather than denouncing a faceless antagonist before a faceless crowd on our digital platforms.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing short and well-made book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Recent reviews: Mona Simpson on Lewis Hyde, Sarah Chayes on Amaryllis Fox’s spy memoir.

Mac’s Backs Books on Coventry, in Cleveland, Ohio, is Book Post’s current partner bookstore. We support independent bookselling by linking to independent bookstores and bringing you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 there during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.