Notebook: Paperback Writers, Part One

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

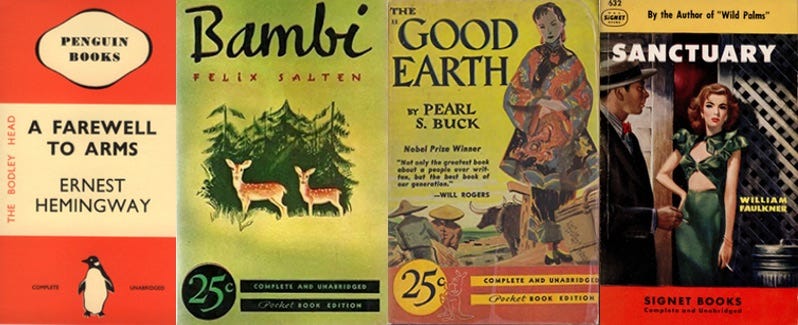

Louis Menand writes in The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War that in the thirties publishers in the UK launched the “paperback revolution” with the idea of selling paperback books for pennies in train stations, drugstores, and newsstands. Bookstores were not widespread and these cheaply produced books, sold from racks through magazine distributors, made books—from classics to pulp—available to many for the first time. Menand writes, “In 1947, two years after the war ended, some 95 million mass-market paperback books were sold in the United States. Paperbacks changed the book business in the same way that jukeboxes, 45-rpm records, and transistor radios changed the music business.” But cheap paperbacks were not a stable business model; publishers had to sell a hundred thousand copies to turn a profit.

A question that’s been circling in my mind: I don’t think readers are aware of this generally, but the way major publishing works, it’s hardcover sales that earn back an author’s advance and make a book profitable for its publisher in the near term. This seems to me to have significant and under-recognized consequences for the demography of the book business.

Who buys a hardcover book? Even I, a die-hard book fan, don’t really have the means to do it all that often. When I buy a hardcover book it’s because I’m pretty confident that it’s going to be something I want to keep and return to. Perhaps other people buy hardcover books because they just can’t wait to read them. But you have to be pretty well off to be buying a $30-plus hardcover on a regular basis. People spend that much money on dinner and clothes, even movies, all the time, you may argue. Maybe so. Something has acculturated us to that level of spending on certain pleasures. It still seems to me a lot to ask that people foot this naked premium for the privilege of having something when it’s new; an object that they are perhaps not likely to reuse. In any case, we don’t seem to be building in such an acculturation to hardcover book-buying among the strapped and skeptical.

The American book market’s reliance on hardcover sales means that much of the marketing energy that goes into promoting books (hence, encouraging reading itself) goes into promoting to the narrow band of Americans who reliably spend $30 on a new hardcover book, perhaps by a first-time author they’ve never heard of. If you are not a buyer of new hardcovers, you are likely only encountering book promotion tangentially (on TV, on a bus). If you take an interest in new books without an intention of buying them (you are waiting for the paperback, which usually comes out about a year later, or you hope to get it out of the library, or you’re just curious but not planning a purchase), book marketing is not made with you in mind; still less if you think that books are not there for you at all.

The business model’s reliance on hardcovers also reinforces the pressure on bookstores to site themselves in places where people can spend money on hardcover books. There are bookstores devoted to paperbacks (San Francisco’s City Lights was founded on this principle), but they are off the radar of publishing promotional budgets. If you follow independent booksellers on social media you’ve probably seen them wrestle with this problem: booksellers enter the business idealistically, wanting to spread the benefits of reading, and find themselves catering to the narrow audience of wealthy, usually older, urban- and suburbanites whose disposable income floats the business. A knock-on problem is that most bookstore employees can’t afford to live where their jobs are.

Subscribe to Book Post’s book reviews

Supporting writers and the reading life

During the #publishingpaidme moment in the midst of last summer’s protests over the murder of George Floyd—when young adult novelist L. L. McKinney invited authors to disclose their book advances under the hashtag #publishingpaidme, revealing that even successful and highly regarded Black authors were not receiving advances comparable to their White counterparts—I hoped this question might get more air. An early-warning-sign on the #publishingpaidme dispute was the ruckus over Jeanine Cummins’ novel American Dirt. Jeanine Cummins was paid a substantial advance, and received the significant marketing push that anxiously dogs such advances, for a book about an experience, American immigration, that many readers found she treated superficially and of which she had little direct experience. Critics lamented that such opportunities are hardly ever given to actual immigrants. But the oft-overlooked element is that an “advance” is not just a payment, it is a pre-payment on expected income. One can make the case that writing a book that will be a commercial bestseller is perhaps not directly correlated with experiencing and describing authentic painful experiences in a way that will make readers uncomfortable enough to do something about them. A big marketing budget can help make a bestseller, but it can’t create a bestseller out of challenging material that masses of well-heeled readers aren’t prepared to hear, or challenging literary forms that a mass audience is not prepared to work its way through. Likely bestsellers, editors will tell you, are not a dime a dozen; there’s an elusive kismet to it. (American Dirt, in the event, spent thirty-six weeks on The New York Times bestseller list.) Usually the breakthrough books of enduring merit that become bestsellers have cannily uncovered an opening in the awareness of a mass readership; or have managed to bring together enough more sophisticated readers (who have many calls on their attention) to gain momentum and register with the bigger world.

What would happen if we published books more inexpensively, so more people would hear about them and a book’s success would hinge on its value for a more diverse group of readers? First-run paperbacks are the norm in most European countries. In Russia, for example, where I have worked, books often appear in hardcover but they have historically been extremely inexpensive (it’s changing). This does seem to lead to (or be caused by?) more widely read populations. A friend who worked for many years at the grand-daddy of the so called “quality paperback houses” (learn about them here), tells me that the economies of these systems differ country to country. The English publishing industry is staggering as paperback-centric and heavily discounted pricing bring in diminishing returns from an aging readership. Book publishing in Germany and France is supported by government subsidy and price protections.

Another factor playing into this discussion is publisher margins. It is commonly said by industry veterans (recently, for instance, by the distinguished Doubleday editor Nan Talese, as I keep quoting!), that after the major houses were bought up by corporations the bosses expected higher returns and major publishers took fewer risks. This would lead to an increased dependence by consolidated corporate publishing on high-margin hardcover sales to wealthy people. Indeed smaller publishers often publish originally in paperback, to increase a book’s potential audience, publishing only in hardcover when they have a high confidence of a motivated audience to buy an heirloom object like a hardcover book. Larger houses sometimes publish a book originally as a paperback when they hope to reach younger readers.

This question of hardcovers and margins plays into two of the high-profile equity issues that have roiled publishing in this year of scrutinizing White supremacy. Why doesn’t the publishing industry distribute high advances (and their concomitant high promotion and marketing budgets) more equitably, and why aren’t staff salaries high enough to allow a more diverse applicant pool? Experienced editors of color have argued (and a recent Panorama Project report has reinforced) that the readership among people of color is not sufficiently tapped by a largely White management structure that doesn’t know that audience’s needs. But it must also be the case in a country in which wealth is overwhelmingly concentrated among White people that they have a disproportionate share in influencing the books that are bought to appeal to people rich enough to buy hardcover books. One might also ask if books are being published that might meaningfully reach the poorer White Americans whose estrangement from the “mainstream media” and learned discourse is having such consequences in our political life. And: with margins already so tight, where does the money come from to pay staff a more livable wage without aggravating the dependence on a moneyed audience?

Since the protests of last summer most of the major publishers have with fanfare raised entry-level salaries; it seems the prospect of reduced costs of remote work, strong pandemic-year sales, and some sacrifices from higher-ups are freeing up some funds. But the structural underpinnings are not clear to me. If publishers were buying books with less of an eye on the rich buyer, and more of an eye on a broad audience, or pricing them to reach a broader public, would they make enough money to pay staff a living wage? Small publishers, who, as Belt Publishing’s Ann Trubek has pointed out, have published many of the authors of color and other marginalized communities overlooked by the big houses, and who are not facing corporate’s exaggerated financial expectations, are scraping by. They are not able to produce advances and marketing budgets substantial enough to redress the imbalances revealed by #publishingpaidme, though they do pay out royalties over the lifetime of a book. Perhaps if they were not facing competition by corporate behemoths in a monopolized distribution environment (Amazon, Walmart), the contrast would not be so stark … (Read Part Two of this post here!)

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Coming soon: John Guare on Tom Stoppard, Rosanna Warren on Edmund de Waal.

The Astoria Bookshop is Book Post’s Spring 2021 partner bookstore! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

So glad you wrote this Ann. I have asked larger publishing houses to do first run in paperback and had that request turned down. As an author, I'd prefer to be first published in paperback as more people will be able to buy and read my books.

this was fascinating, Ann, thank you!